By Marnie Werner & Kelly Asche

In the movies, you can always tell who the “red shirt” is—the guy brought along by the hero and his or her gang for the sole purpose of being the dinosaur’s first victim. He’s the happy-go-lucky guy who scoffs as they peer into the creepy dark cave and says something equivalent to: “What could possibly go wrong?”

In the last week, a series of alarming and sweeping directives have come out of Washington, D.C, and St. Paul that have rocked the heart of our social fabric, all intended to slow the spread of COVID-19, the coronavirus. Schools and universities, bars and restaurants, churches, libraries and every event: it’s like nothing most of us have ever seen before.

A lot of people are scared, even terrified. But others are looking around and saying, “Virus? What virus?”

Sure, we’ve been through scares before: H1N1, avian flu, SARS. Pandemics in the making that didn’t quite make it to the United States.

If you’re old enough, you’ll remember the polio and tuberculosis pandemics of the first half of the 1900s. Nasty, scary, widespread stuff. And then there was the granddaddy of them all, the Spanish flu of 1918-1920.

But for most of us, those are just stories from long ago to scare people with, like rumors of serial killers and the zombie apocalypse. Scary, but stuff that doesn’t happen here, or it happens in other places, or it’s just made up to get ratings or clicks or votes.

And now all these orders closing public places and businesses, wreaking havoc on the local economy. Why? It’s not going to happen here. It’s not going to happen to me.

Well, sorry to break it to you, but it’s happening here, and it’s happening now, in rural Minnesota. Four cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Martin County on Thursday (March 19). Others have been found in Stearns, Renville, Clay, Benton, Rice, Blue Earth, Waseca and other counties radiating out from the Twin Cities.

It’s all about the vectors

Why should people in Lac qui Parle or Koochiching or Clearwater or Aitkin counties be concerned? Because we are a mobile society, more mobile than you may realize, and when it comes to spreading diseases, it’s all about the vectors. The more contagious the disease, the more vectors matter.

What are vectors? Vectors are the carriers that germs hitch a ride with to get from one person to another. All it takes is one person to travel back from an infected area, unknowingly carrying those germs along with him. A handshake, a sneeze, a kiss, and boom, the next person is infected. And like Typhoid Mary, that person doesn’t have to show any symptoms to pass the illness along to multiple people, who go off to infect their own victims.

And no, this is not like the annual flu virus. The characteristic of viruses is that they mutate, always trying to trick our immune systems by coming around each year looking slightly different. But not everyone gets sick from the annual flu because most of us have at least some kind of partial immunity to old versions of the flu virus we’ve encountered before. Our immune systems recognize the virus it once was, either because we’ve encountered it before or we had a flu shot.

No so with this virus. This one is wholly new (hence the term “novel” coronavirus), so we have no built-in immunity to it.

When we’re living in a healthy, normal world, we aren’t usually aware of all the possible avenues germs can travel. Ever drop your cell phone on the floor of a restaurant? You pick it up and stuff it back in your pocket or your purse. No harm, no foul.

That’s because most of the germs we encounter are fairly harmless. If we get a cold, we don’t really care too much where we got it from. The stakes are low. We’re miserable for a few days, then we’re fine.

But ever get food poisoning? Salmonella? E coli? The stakes are bigger there. The discomfort is higher. It can even be life-threatening. Once you’ve had food poisoning, it’s like touching a hot stove. You think twice about eating that burger that’s still bleeding in the middle.

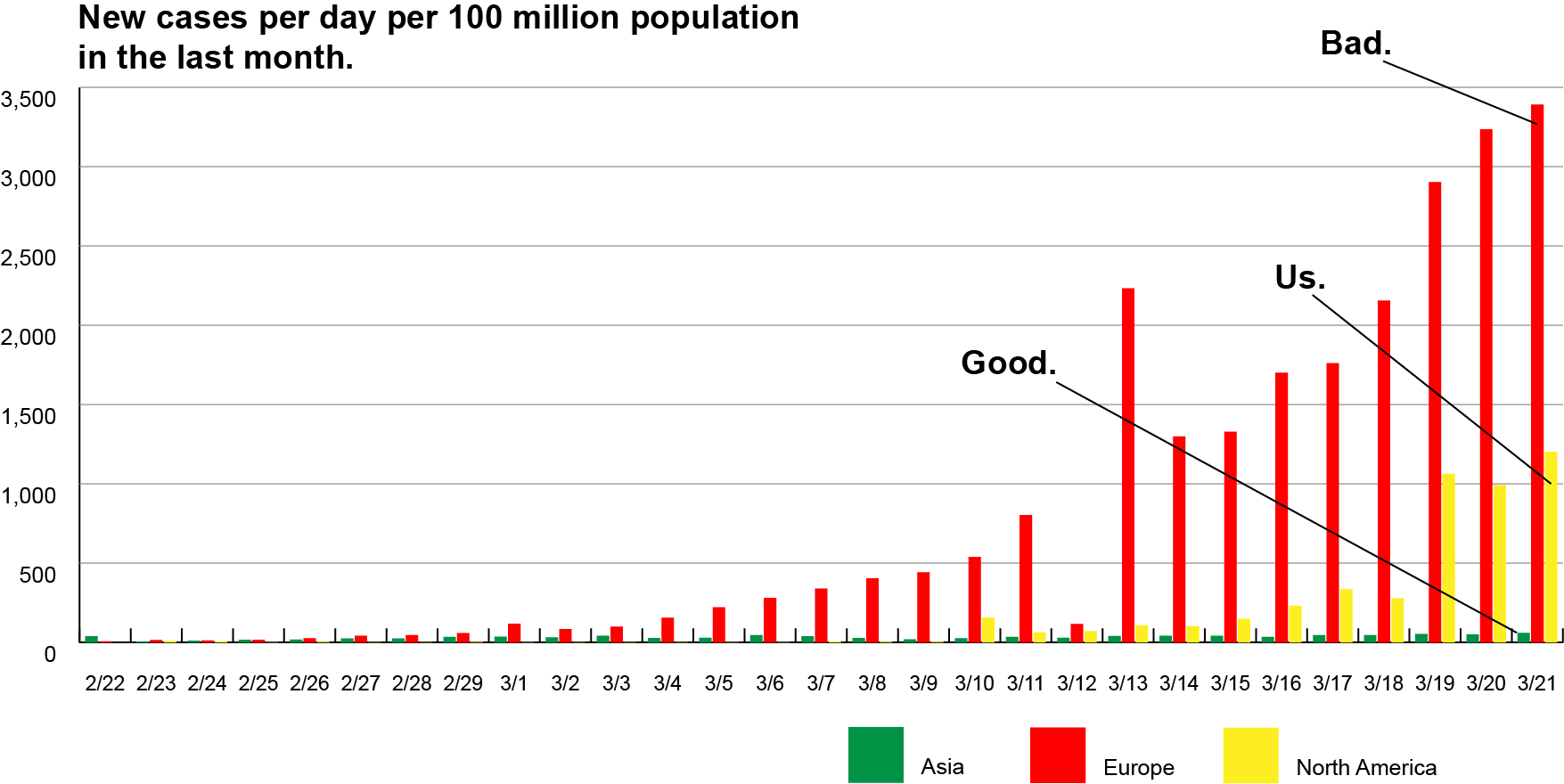

The chart in figure 1 is showing us the hot stove. We’re at a tipping point right now in the U.S. We can slow the spread like they did in Asian countries, or we can let it blow up like in Europe, every infected person infecting multiple people along the way. And we don’t even know how many cases of COVID-19 are really out there. Health officials said over the weekend that there could be 10 times or 100 times as many cases out there walking around Minnesota that we don’t know about because of the shortage of testing.

Figure 1: Over the last month, new daily cases in Europe have spiraled upward while in Asia, they have stayed under control. Numbers of cases are per 100 million population to adjust for differences in population size. Data source: Johns Hopkins University, coronavirus.jhu.edu.

And we’ll say it again: you don’t have to be showing symptoms to get other people sick. That’s the reason for the strategies that were implemented statewide a week ago, back when only a few counties had any official cases. The COVID-19 virus doesn’t care about municipal, county, or state lines. It’s going to hitch a ride with anyone willing to provide one. Think of the truck driver traveling from Seattle to Chicago along I-94 who may get off at a truck stop somewhere. What about friends gathered at a bar for the evening? The family reunion at a hotel in the Twin Cities? The kids coming home from spring break? Everyone leaves and spreads out across the state or nation, encountering other people along their way and after they get home. Vectors.

To be fair, health experts believe that for people who are in generally good health, COVID-19 won’t be life-threatening. Mild to moderate symptoms will range from like having a cold to having the flu. But if you still truly believe it can’t happen to you or it won’t be that bad, try thinking about someone else: your elderly parents, grandparents, friends and neighbors and those with health conditions like heart disease or a compromised immune system. For them, COVID-19 could be far more serious.

Consider this: An analysis conducted by the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team in London used infection and death rates from Italy, China, and Korea to model what would happen in the United States if no strategies were implemented to slow the spread of the virus.

The findings of the report are pretty dire: in an Italy-type scenario, where no effort was made to get ahead of the disease, 80% of Americans would be infected and about 1% would die. The results of their model were far worse for populations 70 years old and older: between 4% and 8% would die. For a summary of the findings, check out this article.

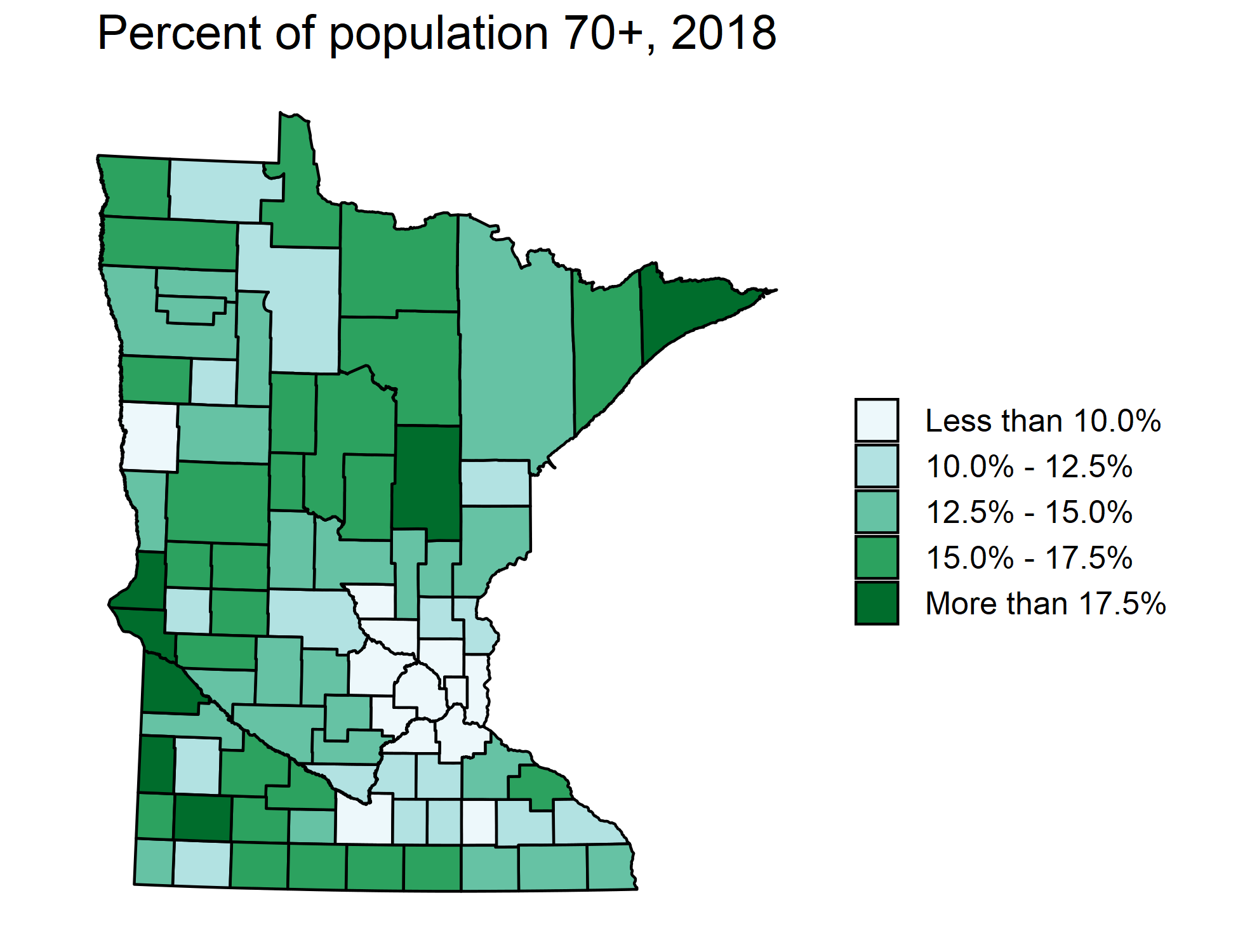

What should give rural Minnesotans pause is that older adults make up a significantly higher percentage of our population than in metropolitan areas (fig. 2). In counties outside of the seven-county metro, individuals 70 years old or older make up 15% of the total population compared to less than 10% in the metro. Aitkin County has the highest percentage of 70+ residents, at 23%.

Figure 2:The percentage of the population 70 years old or older make up a significantly higher percentage of the population outside the seven-county metro area. Data source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 Population Estimates

If we had implemented none of the strategies to limit the spread of COVID-19, the estimated death toll in Minnesota, according to the Imperial College research model, would be over 60,000 people, about 1.1% of the population. The impact would be felt even more in the rural counties where older adults make up a larger percent of the population.

We are in uncharted territory. If COVID-19 follows the usual pattern of pandemics, it could return in one or two more—albeit smaller—waves over the next 12 to 18 months. The decisions we make now will have serious ramifications for the health and economic stability of our state and nation. And even if we do make it through relatively unscathed, there will be other states and other countries that need help.

Think in the long term

The best possible outcome would be that we find ourselves sitting around in the coffee shop next fall complaining about how the government completely overreacted. That’s how we’ll know these measures worked. It’s better than complaining about the loss of life because the government didn’t act fast enough.

We’re not saying be terrified. That leads to stupid decisions like hoarding hand sanitizer and face masks so that now our healthcare workers can’t access the safety items they need to protect themselves and others as they help all the sick patients they’ll be encountering every day, including patients suffering from illnesses other than COVID-19.

We’re just saying, take this seriously. Be concerned but not panicked. Be alert but be sensible. Don’t be Chicken Little, but don’t be a red shirt and blow it off either. If you have your two-month supply of toilet paper, stop buying it and give others a chance. What’s the hotline number your clinic or doctor want you to call if you become sick? What does a six-foot distance look like?

Above all, think about the good of your neighbors and community, and don’t become a vector. For the next few weeks, stay close to home, and for heaven’s sake, keep your distance from your elderly friends and relatives. But don’t cut them off completely. Now would be a great time to introduce them to video chatting or even just more frequent phone calls. Even though we’re all separated right now, we can still be a connected world. Let’s use that to our advantage and stay close. Online.