By: Kelly Asche, Research Associate

The most recent report in our Finding Work or Finding Workers series shed light on what it takes to train and help keep employed that percentage of the population that seems to have the hardest time getting and holding jobs: people with high barriers to employment. With the extremely tight workforce shortage right now, workforce development organizations have shifted their focus from helping laid-off workers find new jobs to connecting this group of individuals with not just jobs but services that will help them keep their jobs.

Everyone involved has recognized the need—whether it’s because of disabilities, a language barrier, a criminal background or extreme poverty, this group needs extra help—and organizations, businesses and the state and federal governments have done an about-face in focus that’s amazingly fast by public sector standards. But like everything that is forced to change quickly, not everything has worked quite as planned.

In “Engaging Workers with High Barriers to Employment,” we discussed what appear to be disparities in workforce development funding that have emerged between Greater Minnesota and the Twin Cities in the past few years. In this post, I want to go a little deeper into how those disparities have come about and what might fix them.

Who distributes the funds impacts where funds go

With the sudden shift in a matter of a few years from finding employment for displaced workers to finding workers for businesses, funding has had to be nimble to provide appropriate programming. Fortunately, funding programs from both the federal and state governments are flexible enough to shift funds toward programming that provides what’s needed in the new environment.

• WIOA and workforce development councils

One of the main sources of funding for workforce development comes from the federal government through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. WIOA has been around since the 1930s, and since the 1970s, it has been gradually decentralizing workforce programs, moving decision making on where and how the money is used increasingly away from the federal government and toward local control.

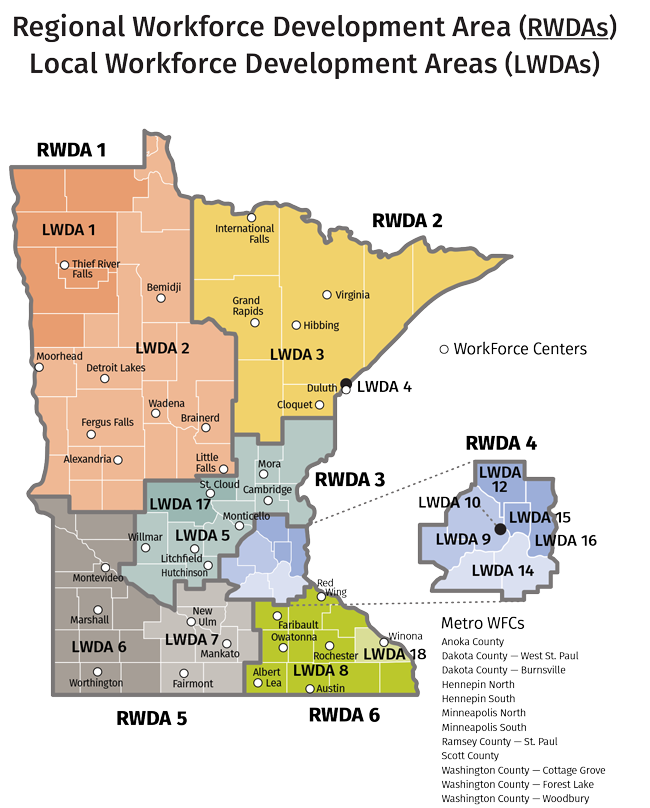

Figure 1 shows how Minnesota is divided into six regional workforce development areas (RWDAs), and each RWDA is divided into one or more local workforce development areas (LWDAs). Each LWDA is managed by a local Workforce Development Board, and the federal government distributes WIOA funds directly to each board based on an allocation formula.

From there, each region’s board distributes the dollars to local public or private workforce development organizations that provide training, and also organizations that provide related support services such as supported housing, transportation or counseling.

• Workforce Development Fund: Disbursed by the state

On the state side, Minnesota is unique in that it supplements these federal workforce development dollars. Minnesota’s contribution takes a rather circuitous route, starting with Minnesota businesses that pay into the state’s Unemployment Insurance Program. A portion of the money from that program then goes to the state’s Workforce Development Fund. From there, dollars go to the state’s various dislocated worker programs, along with the WIOA money.

The fact about the state’s Workforce Development Fund is that it grows significantly during good economic times; fewer dislocated workers need help from state programs, so more money stays in the fund. Recognizing this, money that would otherwise go to dislocated worker programs has over the last few years been diverted to programs that help businesses find workers, including programs helping workers with high barriers to employment. These programs fall into a category at DEED labeled “State Adult” programs.

The devil is in the details

The process used to decide which programs these dollars go to, however, is what seems to have given rise to the apparent geographic disparity that is leaving Greater Minnesota’s workforce professionals shortchanged.

Most of the dollars that go from the State Adult category to workforce development organizations providing services are allocated using either legislative direct appropriations or a competitive grant process administered by the Department of Employment and Economic Development.

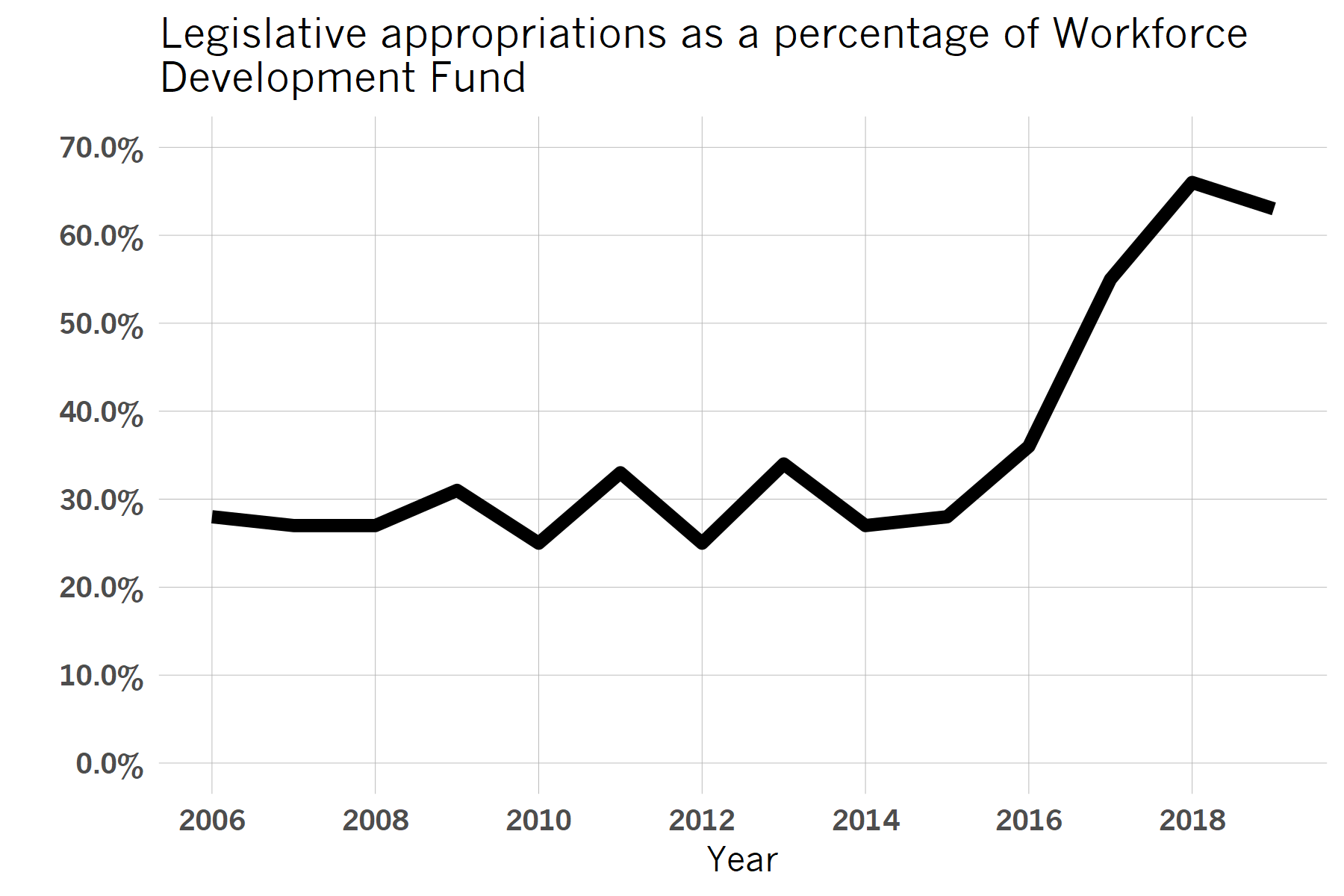

Direct appropriations: Since 2015, the percentage of the Workforce Development Funds being moved from the Workforce Development Fund to programs in the State Adult group via legislative direct appropriation has nearly doubled, going from 28% in 2006 to 55% in 2017 (Figure 2).

Competitive grants: The rest of the funds being moved are allocated using a competitive grant system set up by DEED that disburses funds from programs in the State Adult category to individual organizations doing workforce development.

The strength of both methods is that they allow workforce development organizations outside the typical government agencies to access workforce development funds to provide services, especially those that wouldn’t otherwise be available through traditional workforce training agencies. The grants also encourage competition and experimentation that could lead to innovative solutions.

The issue, however, isn’t who distributes the funds, but rather the instrument used to distribute them.

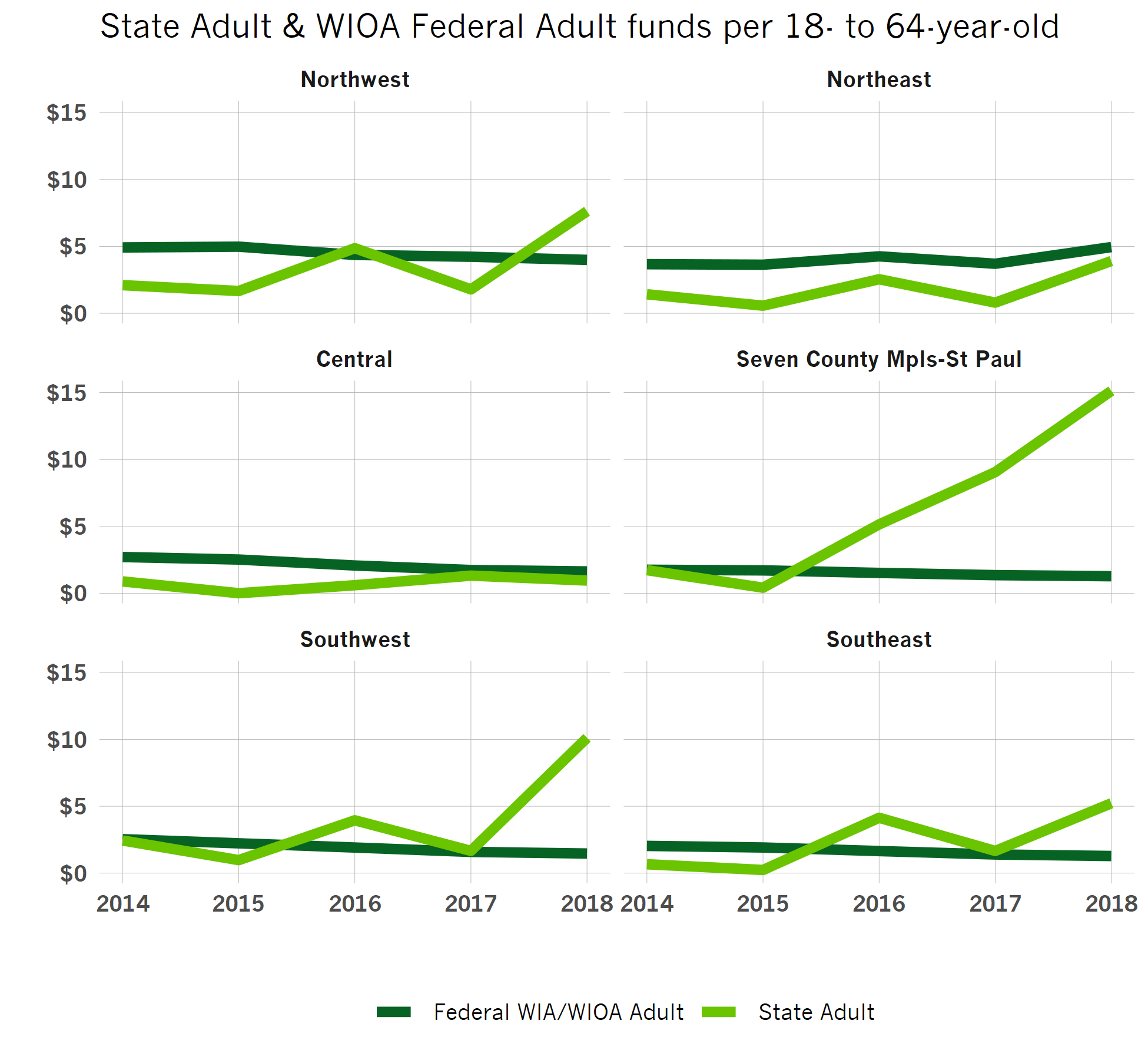

Figure 3 shows that since 2015, there has been a drastic increase in how much State Adult funding is going to the Twin Cities metro area ($15.13 per working-age adult) compared to the rest of the state, even though the proportion of the population using the services has not changed significantly.

The problem, we have found through interviews with workforce development professionals and through our research, is that unlike the federal WIOA funding, there is no geographic factor built into the allocation system for these State Adult dollars. For the competitive grants in particular, the scoring system takes into account many factors, but not location. Therefore, there is no criteria to ensure that the money doesn’t end up all in one place.

Because of this fact, several criteria in the scoring system of the competitive grants process actually work against Greater Minnesota organizations. For example, besides the government-based workforce boards, the Twin Cities also has a much higher number of private nonprofits and community-based organizations providing services compared to Greater Minnesota. The sheer concentration of non-profits and community-based organizations in the Twin Cities increases the odds that more funds will go to the region.

In addition, many organizations in the Twin Cities serve specific populations, but there are almost no corresponding organizations serving Greater Minnesota, even though those same populations also live in Greater Minnesota. Therefore, if the competitive grant process favors organizations serving specific groups, any dollars those groups are awarded would very likely stay in the Twin Cities.

Workforce development professionals in Greater Minnesota also pointed out to us that the scoring system did not take into account the unique challenges of providing services in rural areas, where it costs more per program enrollee because of distance. Because of the more dispersed population, it is also next to impossible to provide the kind of “best practices” the scoring awards more points for, such as the cohort model discussed in our main article.

By and large, workforce development organizations in Greater Minnesota know they have the tools and programs to help people with high barriers to employment and they are building partnerships with other organizations to provide the services, but what they feel like they don’t have is a fair shake when it comes to receiving the funding needed to provide those services. Allowing organizations to compete against each other within their own regions or using some kind of a formula to allocate funds based on geography would go a long way in making sure those dollars meant to help people find and keep jobs gets to those who need them, regardless of what part of the state they live in.