By Marnie Werner, Vice President, Research, & Jordon Barthel, Research Intern

To listen to a conversation with Marnie Werner about this research, check out our podcast – Episode 11: CRPD Research – Census and redistricting in Rural Minnesota.

After months of back-and-forth wrangling among different groups and interests the 2020 Census count finally came to an end last week.

That little postcard that came in the mail inviting you to fill out the Census online may have seemed forgettable, just one more demand on your already-busy day, but next to voting and short of fighting in a war, being counted in the Census is the most important duty residents of the U.S. can perform. Census data is used by everyone from health care researchers to marketing firms to local nonprofits writing grant applications and school systems planning their building capacity for twenty years into the future. Thousands of programs, millions of people and billions of dollars depend on the numbers collected on those Census forms.

But despite all the ways Census data is used today, its most important use is still its first one: the U.S. Constitution requires that every ten years the nation conduct a census of the population for the purpose of readjusting and rebalancing our Congressional districts.

As the founders of our nation expected, populations shift over time, and eventually every voting district, from Congressional down to city council and school board seats, can become unbalanced. The rebalancing process, known as reapportionment, makes one of our nation’s most important principles possible: one person, one vote.

To achieve this equal representation, Congressional districts must all contain as close to the same number of residents as possible, and therefore they must be periodically reapportioned and district lines redrawn, or “redistricted.” In Minnesota, the legislature is charged with the task of redistricting, but despite the importance of this duty, our state’s constitution and statutes offer few explicit rules regulating the process. Redistricting statutes speak more in terms of what is not allowed, namely “malapportionment,” the practice of purposely drawing districts so that, for example, some districts contain more people than others or more voters of a particular party. A landmark ruling in 1964 helped clarify the issue of malapportionment: in the 1964 Supreme Court case Wesberry v. Sanders, when the court ruled that the population of voting districts must be as equal “…as nearly as practicable,” and any difference in population count from the target ideal must be “specifically justified in state policy.”[1]

Minnesota’s statutes require that “…all districts consist of convenient contiguous territory substantially equal in population, and that political subdivisions should not be divided more than necessary,”[2] referring to the idea that all parts of a district must be adjacent (not separated by parts of other districts), and as compact as possible to protect against “gerrymandering,” a practice where parts of a district meander off in order to take in a strategic community or group of people.

The looseness of the rules, though, belies how complex and contentious the redistricting process has been in Minnesota. Since 1958, the state Supreme Court has intervened in every redistricting, making or recommending the final decision, simply because like clockwork, every redistricting bill produced by the legislature has either failed to pass or has died on the Governor’s desk, resulting in lawsuits and accusations of political opportunism by one side or the other or both.

What makes 1958 the watershed year when the courts started stepping into the process? How did apportionment work before that?

The short answer is that it didn’t. Until the 1950s, legislative districts in Minnesota were reapportioned only occasionally and from 1911 to 1958, not at all. During that time, especially after World War II, the state’s population growth had started shifting from rural counties to urban ones. Starting in the mid 1950s, a number of lawsuits were filed demanding that the voting districts be redrawn to be in compliance with the current Census counts. The outcome was a shift in the legislature—rural districts grew in area while districts in population centers, especially in the Twin Cities counties, shrank in area, which resulted in more legislators from the Twin Cities and fewer from Greater Minnesota.

Since then, population growth in the Twin Cities metropolitan area has continued to outpace growth in the rest of the state, which for Greater Minnesota, then as now, has meant a decreasing number of legislators representing the region.

|

Table 1: Twin Cities legislators held the majority in the legislature briefly after the 1970 Census, then for good after 1990. |

|||

|

Year of Redistricting |

Legislative seats in Twin Cities seven-county region |

Legislative seats in Greater Minnesota |

% of all Legislative seats in Twin Cities metro |

|

1958 |

73 |

128 |

36% |

|

1962 |

73 |

129* |

36% |

|

1972 |

102 |

99 |

51% |

|

1982 |

96 |

105 |

48% |

|

1994 |

104 |

97 |

52% |

|

2002 |

109 |

92 |

54% |

|

2012 |

114 |

87 |

57% |

This happens because while the population of the state has continued to grow (from 4.8 million in 2000 to an estimated 5.6 million in 2019), the number of state senators and representatives stays the same at 201, meaning the target population of each district will increase. The target population of each Minnesota House district based on the 2000 Census was around 36,000, while the target population resulting from the 2020 Census is expected to be around 42,000. When it comes time to redraw the districts in 2022, many rural districts will turn out to have fewer residents than the target population and will need to expand in geographic size to take in enough people to reach the target. Districts that have grown in population, meanwhile, will have too many residents and will need to shrink to get down to the right number.

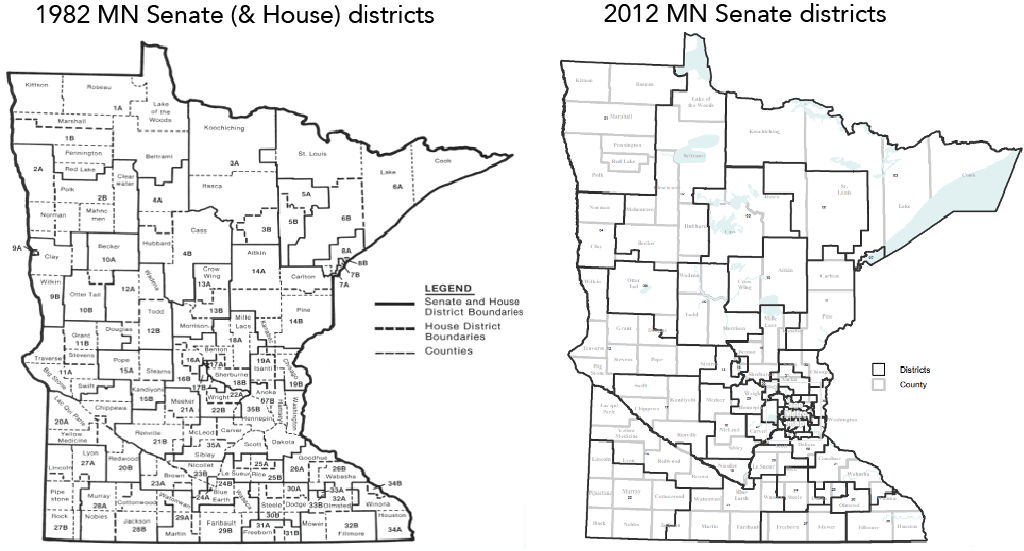

The two maps below comparing 1982 legislative districts to current districts show just how the districts have shifted and changed shape over the years.

A tilting balance of power

When the number of Greater Minnesota and Twin Cities legislators was mostly balanced and both parties represented both rural and urban/suburban districts,[3] legislators could form alliances across political and geographic divides to get bills important to both urban and rural districts passed. As the number of Twin Cities legislators grows past 50%, however, this practice of reciprocal support becomes less important for urban/suburban legislators.

The growing number of urban districts can in fact impact the ability of largely rural issues to even “make the agenda.” The legislative system relies on filtering bills through committees before they go to the full legislative body. Recognizing that it is simply not possible for all issues to go before a committee or to receive equal time, it is up to those committees to choose which bills will be considered.

Individual members of these committees play a significant role in deciding which issues advance (or are left on the table). As more and more legislators come to the House or Senate from urban and suburban districts, the number of members on these committees will likewise lean toward urban and suburban districts. A quick look at the chairmanships of four key committees in the House and Senate since 1957—Agriculture, Education, Taxes and Transportation—shows that over those 63 years, rural legislators have been as likely as urban legislators to control the chairs in those committees in each session. (Except in Agriculture, which understandably has been chaired by rural legislators almost exclusively.)

Much of that consistency, though, is due to the fact that for many years, legislative seats were non-partisan. Legislators didn’t have to align with one party or another, and so with no one party “in power,” it was possible for a single individual to hold a committee chair for a very long time. So instead, let’s compare two time periods—1957 (just before reapportionment began happening again) to 1990 and 1991 (when the Twin Cities metro began representing 50% of legislators) to today. The shift in chairmanships is noticeable.

|

Table 2: Between 1957 and 1990, a majority of chairs in these key committees came from Greater Minnesota. That trend started to change after 1991. |

||||

|

Committee |

1957-1990 |

1991-2020 |

||

|

Committee chair lives in: |

Twin Cities metro |

Greater MN |

Twin Cities metro |

Greater MN |

|

Agriculture |

12% |

88% |

10% |

90% |

|

Education |

44% |

56% |

83% |

17% |

|

Taxes |

26% |

74% |

47% |

53% |

|

Transportation |

12% |

88% |

53% |

47% |

It’s logical that urban legislators would focus more on urban issues. They are after all tasked with representing their constituents. But the situation becomes a problem if Twin Cities legislators no longer see an incentive to cooperate with rural legislators.

Ultimately, our population trends aren’t going to reverse, at least not drastically, which means an urban-rural divide, no matter how it is framed, will eventually pit the social, political, and economic needs of each region against the other. While urban and rural citizens likely have similar ideas about the fundamental services their governments should provide, the intensely competitive nature of politics inevitably results in winners and losers.

Now would be a good time to start conversations with our local government and community leaders to work on solutions to our problems, shared or otherwise, that don’t involve pitting rural interests against urban and suburban interests, and to talk with our neighbors in the Twin Cities about where our interests align and the important roles each region plays in the ongoing health of our state as a whole.

Revised Oct. 22, 2020.

* There were 202 legislators in 1962.

[1] For example, in the case of Shelby County v. Holder.

[3] Minneapolis Star Tribune, “Trump supporters eye disenchanted Democrats in greater Minnesota,” Aug. 25, 2020.