by Marnie Werner, VP, Research & Operations

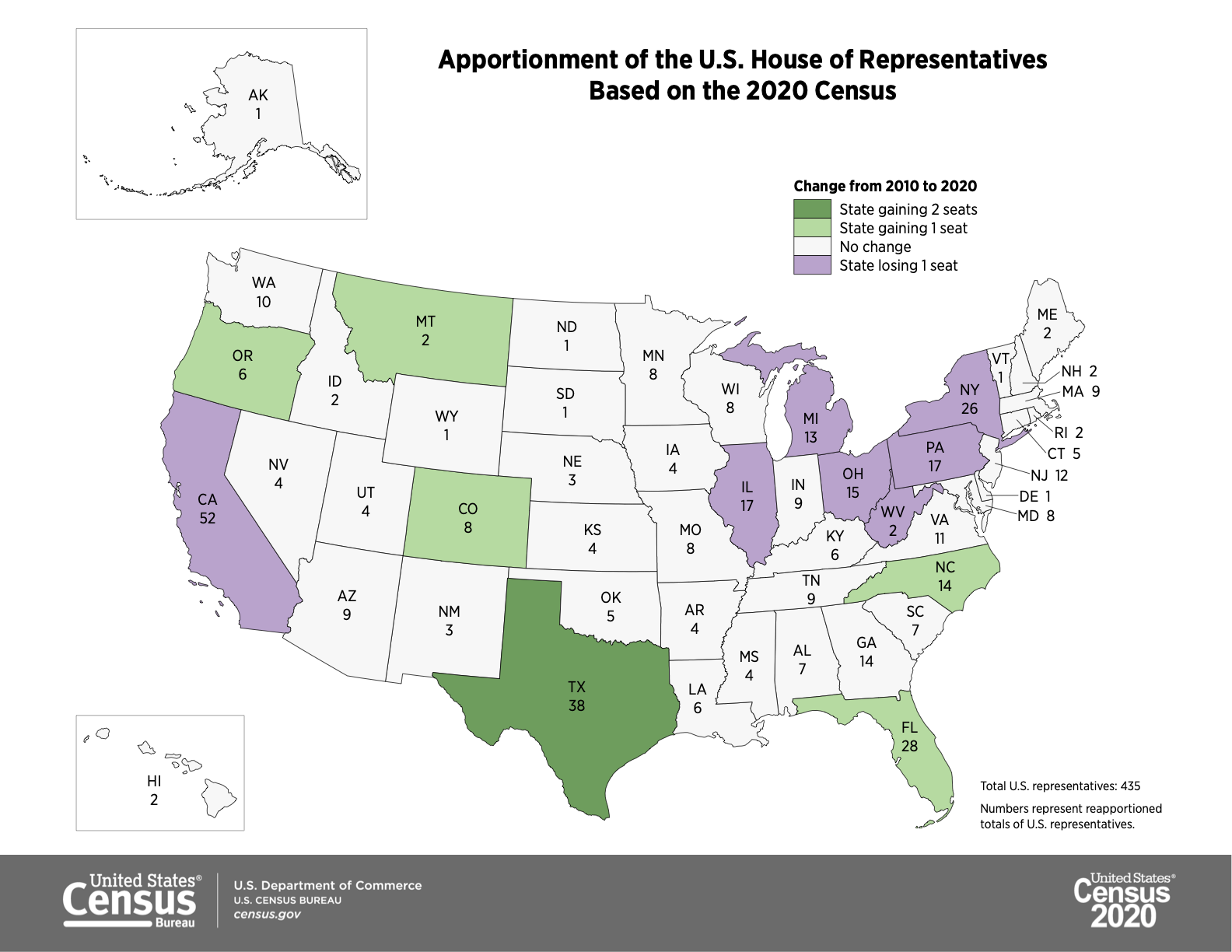

The Census Bureau released the first round of data from the 2020 Census last week, and it was a nail-biter. These are the basic numbers, the new 2020 population of each state, which is used to determine how many seats each state will get in the U.S. House of Representatives.

A close call

For Minnesota, this year’s Census outcome was a genuine squeaker. Everyone who pays attention to this sort of thing thought Minnesota was going to lose a Congressional seat. But we didn’t. Instead, we scooted past New York, managing to keep all eight of our districts, but by the narrowest of margins: if Minnesota’s count had totaled 26 fewer people or if New York had come up with 89 additional people, we and New York would have flip-flopped, leaving them with the same number of districts and us with one less.

Like we wrote about last October, the Census’s first and most important purpose is to determine how to divide up the 435 seats in the House of Representatives. The number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives is fixed. As the size of the nation grows, they don’t add more desks to the House chambers.

The nation’s population fluctuates, though, as people move to this state or out of that state, so the purpose of the Census is to ensure that the representation of each Congressional district stays as balanced as possible. If this every-ten-year adjustment didn’t happen, quickly growing states like Texas and Colorado would be dominated in the House by states that were once big but were now losing population, holding steady or just not growing as fast.

So instead, once the Census Bureau has collected all the data and has determined the populations of each state, they calculate a ranking based on that population to determine which states gained population fast enough to hold onto their seats or even gain one and which states would lose one.

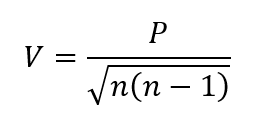

Here’s the equation used to calculate the rankings. Don’t ask me to explain how the Census Bureau’s demographers arrived at this particular formula, but the resulting values give a numeric rank to each Congressional seat in every state. Put in order, the state with seat 435 gets a seat inside the House chambers. Seat 436 is stuck on the outside. And so, this time, unlike so many Minnesota sports teams, we as a state managed to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat by coming in 435th out of 435. Our eighth district got the last seat. New York’s 27th district was number 436.

Every person counts

Losing a seat is kind of a big deal, although for New York, going from 27 to 26 seats, it’s probably more hurt pride than any loss of actual representation. Losing a seat in Congress looks like you’re losing population even if—as in New York’s case—you’re growing. It feels like being relegated to the minor leagues. Lots of head-shaking and tsk-tsks. Poor New York. If they had only had 89 more people.

But when you have to draw a hard line somewhere, in this case just under Seat 435, every person really does count. That’s why here in Minnesota, we made a big public push to make sure everyone was counted. There’s no “oh, you’re close enough—we’ll let you keep that Congressional seat.”

Ideal district size and the work of representation

Losing a seat in Congress does amount to a little bit more than hurt pride, though, even if you’re New York. When your state loses a seat in Congress, we as individuals lose a bit of our representation.

If Minnesota had lost a seat, we would have lost our eighth district and therefore one eighth of our votes in Congress. (This is why the founders of our nation also created the Senate, so that even little states would have an equal voice against the big states.)

We wouldn’t literally lose the Eighth District, of course, which covers essentially the northeast quadrant of Minnesota. Instead, the shape of our Congressional districts would have had to change, and the ideal district size for each of our districts would have grown substantially, from 663,000 residents per district based on the 2010 Census to a whopping 815,000 per district. So every Minnesotan would have had a little less representation.

But we didn’t lose our eighth district, so now Minnesota’s new “ideal district size”—how big each of our eight districts should be to be even—is a little over 713,000 people, and Minnesota’s Congressional districts will still have to be redrawn to account for our growth in population over the last ten years, a little over 400,000.

Over the next year or so, there will be a lot of district borders shifting around, not just for Congressional districts but for all elected districts, from the state House and Senate right down to city and township precincts. Districts with populations smaller than the ideal district size will have to expand to take in more people, while districts with populations above the ideal district size will have to shrink their borders to get down to the right number. Some elected officials may find themselves redistricted into a different district, possibly even with a fellow official from the same party. Other districts may find themselves without a representative, and so a new candidate must be found for that seat.

It’s a lot of work and there will be many contentious days (and nights) while officials hammer out the new boundaries, but fortunately this only happens every ten years. But hey, Minnesotans’ hard work paid off and we kept a Congressional seat! It’s all good.