May 2017

In 2014, the Center took a serious look at the issue of water in Minnesota. Can the Land of 10,000 Lakes really have a problem with its water supply? It turns out that yes, it can.

In a follow-up to this article, we partnered with the Center for Small Towns at the University of Minnesota—Morris to take a closer look at the issue of water. Wastewater treatment is not an attractive topic, but it is one of the most important components of a functioning community, protecting the health of residents and the larger environment. A functioning system is vital to quality of life and to economic stability and growth, but our survey and an accompanying analysis found that smaller communities are having a certain level of difficulty keeping up with maintenance and mandated upgrades, while at the same time they have less capacity to afford this maintenance compared to larger communities.

Wastewater Challenges in Small Minnesota Communities, full report

Operators are facing challenges

The survey conducted by the Center for Small Towns asked operators about specific issues they might have difficulty with and found that certain ones stood out.

Researchers selected and contacted a sample of 200 operators from towns under 20,000 in population (there are 657 cities of that size in the state) to ask them about specific issues they may be facing with the operation and condition of their systems. They received 76 responses.

The most prevalent problem for almost two thirds of the respondents (63%) appears to be that of infiltration and inflow, a problem resulting mainly from storm water and groundwater infiltrating the wastewater system through cracks and breaks in underground pipes. It can also be caused by improperly connected sump pumps.

Only waste solids and wastewater should be entering the system to be processed in the community’s treatment plant. The problem with infiltration and inflow for cities is that as outside water gets into the system, it is also—and unnecessarily—processed through the treatment plant. It’s a waste of chemicals and equipment such as filters and therefore a waste of money, but there is also no way to keep it out except by addressing where it is coming in. Thirty-four percent said their biggest I&I problem was caused by rain, while 26% said aging infrastructure.

Three-quarters of the survey respondents said their communities had plans to address the influent and infiltration problems and were implementing them. Most of the programs involve disconnecting sump pumps, using remote-controlled cameras to check on the condition of pipes, and replacing old infrastructure, including replacing clay pipes with PVC. The biggest hurdle to doing these programs for one-third of the communities, though, was funding, they said.

The primary purpose of a wastewater treatment facility is to remove contaminants before releasing it into back into nature. Regulations give specific limits that contaminant levels should not exceed, but meeting those limits pose a challenge for communities, especially as the target limits change. More than 60% of respondents reported having consistent problems meeting specified parameters for various contaminants that need to be filtered out in the treatment process, and 25% reported dealing with more than one issue. The largest problem cited was that of phosphorus (35% of respondents). At the same time, one third of respondents reported that their communities have had to make expensive upgrades to their systems due to increased and/or new permit limits.

Analyzing the impact on certain households

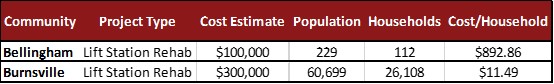

The costs to upgrade, replace, and maintain wastewater infrastructure are usually spread across all households in a community in the form of rates. It may be intuitive to think that smaller communities pay less for infrastructure since there are fewer households to serve. There is a certain amount of overhead with constructing and operating a wastewater system, however, that must be paid regardless of the size of the community. The result in that case is that the cost per household served in smaller communities is generally higher than it would be in a larger community. An example in the report illustrates this with the construction of lift stations in Bloomington, MN, and Bellingham, MN. Even though the Bloomington lift station is larger and costs more in total to build, the Bellingham lift station costs more per household.

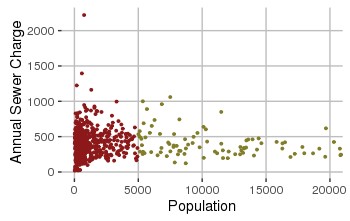

In communities under 5,000 population, the median sewer rate of a typical household (around 60,000 gallons of water annually) was 21% higher than for larger communities (over 5,000). While the chart below shows that annual sewer rates tend to vary more in smaller communities, in general, they decrease with increasing community population.

The researchers also looked at the impact of rates on the household budgets of the population over age 65 and the low-income population using the same 1.4% of income threshold used by the Environmental Protection Agency to represent the amount of income wastewater rates should cost. It’s an important comparison since, compared to larger communities, smaller communities tend to have a higher proportion of elderly households and lower-income households and in turn a lower proportion of higher-income households.

When comparing the medians, researchers found that householders 65 or older in smaller communities were paying on average 0.49 percentage points more of their household income toward sewer rates than the same age group would in larger communities. Sewer rates as a percent of median household income for those 65 and older in general decreased with increasing population.

Researchers found a similar pattern with low-income households. Using a threshold of $35,000, they found that households in smaller community households with incomes less than $35,000 were paying more of their household income for sewer rates than their counterparts in larger communities.

The study comes to the conclusion that while small communities in Greater Minnesota are actively working on their biggest wastewater problem—infiltration into their wastewater systems—lack of funds continues to be a problem. To spread the total cost over the population of a small town results in higher rates for residents and businesses compared to larger communities. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s annual WINS report backs this up with its survey of municipal rates. Higher rates can have an impact on economic development and even livability as families choose where to live. Further attention to this issue is in order to help keep small towns, their residents and their environments healthy and productive.