download a pdf of this two-page infographic.

A discussion on the complex relationship between rural communities and our state’s most valuable resource

by Marnie Werner, research director

Andrew Hayes, research intern

Can people who live in the land of 10,000 lakes really have a water problem?

The city administrator of Worthington says yes, they can.

Worthington, a community of 12,500, sits on busy I-90 in the very southwest corner of the state, not too far from Sioux Falls. It’s an area of high prairie and little groundwater.

“Historically, we’ve always been challenged with water, but it’s really acute now,” says Craig Clark, Worthington city administrator.

The city is now purchasing 500,000 gallons of water every day from neighboring Lincoln-Pipestone Rural Water System while the city’s municipal wells continue to decline. And while the city’s largest business and largest water user, pork processor JBS, has managed to reduce the amount of water it uses per animal, strict USDA standards say the processor cannot use less than a certain amount. Worthington would like to recruit more ag-related businesses, but it’s out of the question right now, Clark says. “The water situation puts us at a competitive disadvantage.”

Now a solution Worthington and others in the region have been working toward for years is being threatened by a decrease in federal funding. The massive Lewis and Clark Regional Water System is supposed to deliver water from the Missouri River to twenty cities and rural water systems in South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota. However, cuts in federal funding have stopped the project dead for the most part, literally at the Minnesota state line.

Meanwhile, in the southeast corner of the state, the problem for the city of Lewiston is not quantity of water but quality. One of the city’s two municipal wells is contaminated with nitrates from agricultural runoff while the other well has been found to be contaminated with radium, a heavy metal that occurs naturally in the region’s sandstone bedrock. The city is currently blending water from the two wells to address the nitrate issue but it also needs further upgrades to take care of the radium.

The city’s original plan involved drilling a new well in the Mt. Simon aquifer and constructing a water filtration plant to filter out the radium, at an estimated price of $3.1 million, a cost that would effectively double water rates and put a considerable strain on the city’s finances. By working with its engineers and the Department of Health, the city devised a new plan to drill a new well in the Wonewoc aquifer, which tests indicate is clear of both nitrates and radium. The cost of this plan, including a line to bring in water from the old well so it can be blended to lower the nitrate levels, is estimated at about $1 million.

And up in Two Harbors, on the north shore of Lake Superior, the issue is bedrock and wastewater. The city sits on a solid shelf of hard rock that underlies most of the Arrowhead region of the state. Here, laying pipe doesn’t mean digging a trench, it involves chiseling a channel out of solid stone, says Bill Dunn, an analyst for the Municipal Division of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. The city found that in a heavy rainfall, the rainwater rushed into the wastewater system and flooded it, stirring up the waste and flushing it out into Lake Superior before it could be treated. To replace Two Harbor’s entire system would have cost $7 million, according to Dunn, but a $2 million solution was built instead: an equalization basin that can be filled when significant rainfall occurs. The water can then be released into the system afterward at a controlled rate.

In addition, data from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources indicates that all over the state an alarming amount of water goes unaccounted for because of leaky pipes or bad record-keeping or both, resulting in a substantial expense in wasted treatment chemicals and pumping costs for cities and potential hazards to the environment.

Water is a vital resource for human and community life, but for rural communities, especially small ones, issues of water are particularly problematic and expensive. The topic of water is vast, ranging from lakes and streams to lawn watering, so we focused on only two aspects of the issue: accessing groundwater and cleaning it up.

The environmental and health impacts of water quality are well known. The Minnesota Department of Health has clear guidelines on what levels of various pollutants are considered safe, and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency constantly monitors the health of aquifers and watches for new “contaminants of emerging concern.”

What is less well known is the impact of water on economic development. How many cities that would otherwise have growing economies are held back because their water supply or their infrastructure is strained to the point where the state must impose a moratorium on adding one more home bathroom or business restroom?

Community leaders “with a can-do attitude, coupled with effective local institutions, can often be the factor that separates those communities that move forward from those that lag behind.”[1] But public infrastructure plays a crucial role. For those communities that do have that mix of leadership and will, having inadequate water and wastewater infrastructure can be the roadblock that cancels out everything else. A municipality has no chance of growing without adequate water or wastewater facilities, says Ruth Hubbard, executive director of the Minnesota Rural Water Association.

The irony, though, is that to make those infrastructure improvements, cities need a tax base from which they can raise funds to pay off infrastructure loans. And to get that tax base, they need economic development. The smaller the city, the smaller the tax base, and therefore, a decreased ability to pay for the necessary improvements.

There are solutions, whether through new technology or conservation methods, but one thing lawmakers must be sure of is that Greater Minnesota’s mid-size and smaller cities are not left behind, particularly the smallest cities. These small towns have on average the oldest infrastructure, the fewest resources to pay for upgrades, and the most fragile economies. But their problems aren’t just local problems. They are everyone’s problem, because the simple fact is that the vast majority of our water resources and our water infrastructure that pumps, moves, and cleans our water is found in Greater Minnesota.

The 800-pound gorilla: wastewater infrastructure

About three quarters of the state’s residents and businesses are served by 680 public wastewater systems across the state, including both municipalities and regional systems. The remaining 25% are served by private residential septic systems, plus private septic systems used by businesses, schools, nursing homes, churches, and other places where people gather.

About three quarters of the state’s residents and businesses are served by 680 public wastewater systems across the state, including both municipalities and regional systems. The remaining 25% are served by private residential septic systems, plus private septic systems used by businesses, schools, nursing homes, churches, and other places where people gather.

Wastewater infrastructure, in particular treatment facilities and sewer lines, are in regular need of maintenance and upgrades, and both communities and businesses depend on it being there. When a community’s treatment facility falls below a threshold where it can no longer function at the necessary capacity, the PCA is required to pull that city’s permit, effectively imposing a moratorium on adding any additional lines, and therefore stopping any development.

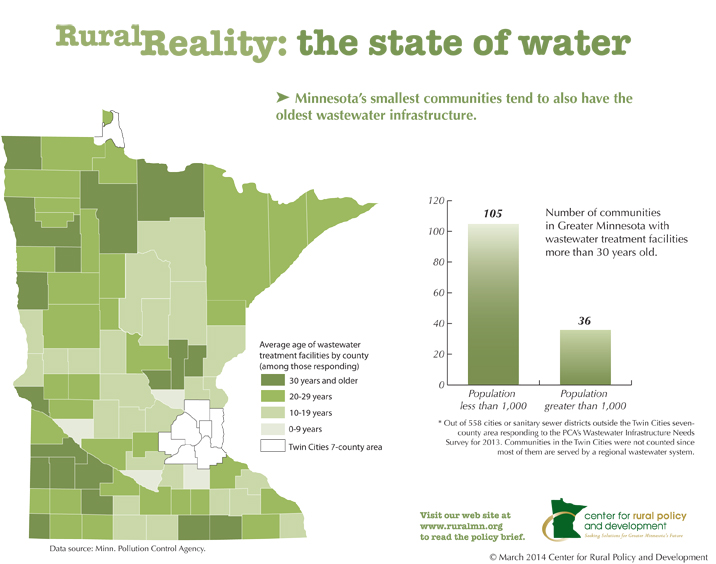

The PCA conducts a Wastewater Infrastructure Needs survey of systems every two years, and the data collected shows that Minnesota has a large number of very small cities operating their own wastewater treatment facilities.[2] Almost 60% of the Greater Minnesota cities that responded to the PCA’s infrastructure survey—270—have populations of less than 1,000.

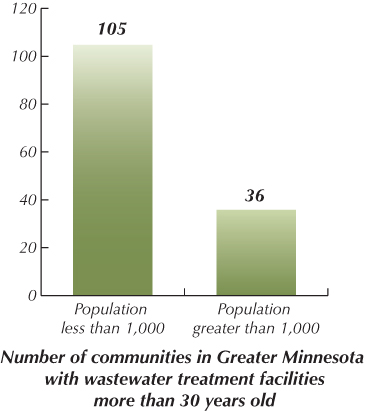

facilities by county.

These communities also tend to have the oldest infrastructure. Out of those 270 small communities, 105 reported their wastewater treatment facilities as being at least 30 years old, which is approaching the end of a wastewater facility’s normal lifespan of 30-40 years. Of the 190 communities larger than 1,000, only 36 reported their facilities to be more than 30 years old. Indeed, on average the oldest wastewater treatment facilities can be found in the most rural counties (see map).

Water-rich regions? Water-poor regions?

Approximately three fourths of the state’s population uses groundwater, including virtually all of Greater Minnesota. The ability to access it, however, varies drastically around the state. Where you are makes a difference. The city of Worthington has spent more than $500,000 over the decades exploring for new places to put wells with little success. According to Minnesota Department of Natural Resources official Jason Moeckel, the water of southwestern Minnesota is not plentiful and it’s not of great quality, making it less than ideal for humans and livestock unless it is treated. But Worthington is a city poised for growth. Their water, or lack of it, is holding them back.

The quantity and quality of groundwater vary considerably from region to region. Because of geology, groundwater is harder to access—and easier to contaminate—in some parts of the state compared to others. The map at right shows the layout of Minnesota’s “groundwater provinces,”[3] which are determined by two layers of earth—consolidated (bedrock) and unconsolidated (sand, gravel, dirt). How the bedrock and soil layers come together in any one part of the state determines how plentiful water is there and how easy it is to contaminate. (Click here to learn more.)

U of M Water Resources Center

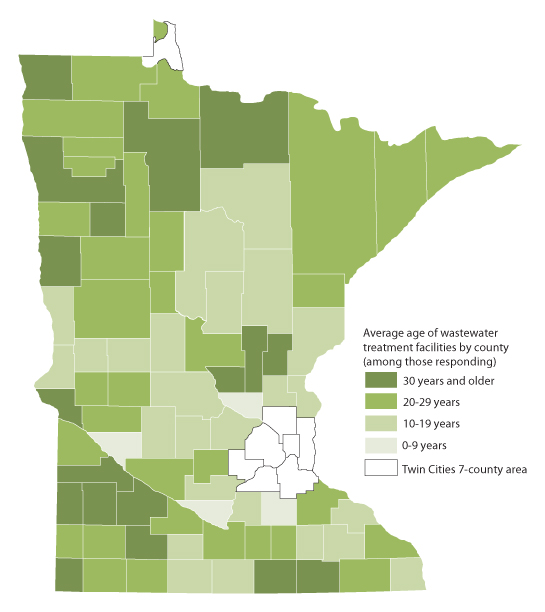

For example, the Twin Cities metro area sits in the sweet spot of the state water-wise. With a combination of sedimentary bedrock that holds water like a sponge and sandy, gravelly soil that allows rainwater to recharge those aquifers quickly, the Metro area has access to an abundant supply of clean, fresh water. The strain from population growth over the decades, though, is starting to show. Part of the reason White Bear Lake is disappearing has been attributed to the drought of the last few years, but experts are also speculating that as suburbs spread further out around the margins of the Twin Cities area, serving their growing populations with new wells sunk into the same aquifers that feed the rest of the metro, the water supply is going down faster than it can be recharged, especially in drought years.[4] The situation has become severe enough that the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has created a “water management district” in the northern and eastern metro that includes all or some of 51 cities and townships. The DNR has the authority to create these districts and impose special water use regulations within them when their monitoring indicates the situation is serious enough. Two more water management districts have been designated in Greater Minnesota, one in the Park Rapids area and another in the Bonanza Valley area of central Minnesota that will address groundwater contamination.

The amount of groundwater being used in Minnesota is growing faster than the growth in the state’s population, says Moeckel, manager of Inventory, Monitoring and Analysis for the DNR’s Division of Ecological and Water Resources. The DNR tracks water levels using 750 monitoring wells around the state. DNR data shows that the amount of groundwater being pumped out and used grew 41% between 1990 and 2012, while data from the U.S. Census indicates the state’s population grew by only 23% in that time. The DNR is currently analyzing twenty years’ worth of detailed data, and while they can’t yet say conclusively that sinking levels in some areas are ongoing trends or that it is caused by human activity, Moeckel does say that Minnesotans are using more groundwater than ever.

Lost water

There also appears to be an alarming amount of water going unaccounted for because of leaky pipes. All water infrastructure leaks, says Moeckel, and for each community, any leakage means dollars down the drain in wasted treatment chemicals and pump fuel. It can also mean a significant savings when the problem is fixed. For some communities the amount of current water loss is critical.

Anyone with a permit to pump groundwater (and anyone who pumps more than 10,000 gallons a day is required to have a permit, from a municipality to a farmer),[5] must report to the DNR how much they have pumped. A check of data supplied by the DNR shows that among the 264 communities under 1,000 population with permits for their public water systems, 192 didn’t report either the amount of water pumped out of the ground or the amount used by the end user, or their reports showed more water used than pumped.

Of the 72 communities remaining, the median percentage of water pumped then apparently lost along the way was 20%, meaning half of the 72 communities on the list were losing more than 20% of their water in transit. The highest calculated losses were 62% and 63%. Some of that apparent loss is due to inaccurate meters, unmetered use, or using estimates when reporting, says Sean Hunt, with the DNR’s Water Regulation division. Yet while there may be extenuating circumstances, it’s still a staggering figure, totaling a combined 18 million gallons unaccounted for by the two cities.

A related threat to groundwater is that of unpermitted pumping. A recent review of state data by Minnesota Public Radio revealed that an estimated 200 wells have been pumping millions of gallons of groundwater without the required DNR permits, hindering the agency’s ability to monitor groundwater quantity and quality.[6]

Contamination

Different areas of the state also deal with different types and levels of contamination in their groundwater. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture are responsible for monitoring water for contaminants, while the Minnesota Department of Health determines what are safe levels. The PCA watches for anything considered a non-agricultural contaminant, says Sharon Kroening, the PCA’s research scientist who oversees the agency’s monitoring well network. The PCA has a network of 115 wells statewide, measuring levels of nitrates, phosphates, trace heavy elements such as cadmium, lead, and arsenic, and volatile organic compounds such as those found in gasoline and benzene, plus naturally occurring contaminants like radium. The PCA is also collecting and analyzing data on the trends in “contaminants of emerging concern,” Kroening said. Some of the chemicals trending upward are insect repellants such as DEET, detergents, road salt, and medications.

While communities usually draw their water from deeper wells, the PCA monitors shallower wells, Kroening says, allowing scientists to see and do something about contaminants before they have a chance to filter down into the deeper reaches of aquifers later on. Contaminants deeper down are much harder if not impossible to address, Kroening says.

The city of Lewiston, with its problems of nitrates and radium, is very susceptible to contamination in its water supply because not only does it sit in an agricultural area, it is also in the middle of the “driftless” region of Minnesota, an area that was not overrun by glaciers. Rainwater soaks through the limestone and sandstone bluffs within hours, carrying contaminants with it. As part of their plan to address the problem, the city has adopted a Wellhead Protection Plan that regulates land use in areas where activity can especially affect the groundwater beneath. (Minnesota Public Radio has a collection of examples of rural residents working to protect their water supplies from contaminants.)

Paying for it all: economies of scale

Maintaining and improving infrastructure is made more difficult for smaller cities because of economies of scale, which work against small communities when it comes to financing large capital expenses. The smaller the population, the larger the cost per household; small communities also tend to have small tax bases, often based on property values that are lower compared to those in larger cities. Small rural cities also tend to have lower median household incomes and more people on fixed incomes. Tackling a major upgrade can result in a significant increase in water and sewer rates. Raising rates is not only a burden for communities, but it can make the city uncompetitive compared to surrounding towns.

The force behind economies of scale is distance. Distance between communities and between paying customers means the project requires more resources, adding to its cost. The Twin Cities has seized on the power of economies of scale through regionalization under the auspices of the Metropolitan Council. Metropolitan Council Environmental Services serves 112 communities in the seven-county area, handling wastewater at seven treatment facilities around the metro. Calculations done by the PCA show that MCES communities have the lowest average sewer rates in the state.[7] The MCES system serves about 250,000 residents per treatment facility. In comparison, the 270 facilities in cities under 1,000 mentioned above serve on average 681 residents.

To determine which communities have the greatest need when it comes to funding infrastructure, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency maintains a Project Priority List, using a point system based on several factors, including age and potential for pollution. This year’s Project Priority List shows a total of 330 projects ranked from 105 points down to 1 point. Of the top 50 projects on the list, 43 are in small cities, townships and sewer districts in Greater Minnesota.

Here’s the stark reality of the cost, however: Seven out of the top fifty projects are in Minneapolis (3 projects), Duluth, Mankato, Loretto (in rural Hennepin County) and Afton (in rural Washington County). These projects together will serve around 1.3 million people at an estimated cost of $19 million. The other 43 projects will serve an estimated 60,000 people[8] at a projected cost of $149 million. This is the power of population density and economies of scale at work.

To help communities pay for these capital costs, the state offers an array of financing options that cover everything from wastewater to drinking water to straight pipes and septic systems. The state’s Public Facilities Authority manages loan programs and a grant program, the Wastewater Infrastructure Fund.[9] The Minnesota Rural Water Association and the Pollution Control Agency also offer funding assistance.

The problem is, to obtain a loan, a city needs to be able to repay it, and that becomes a problem for very small cities that are suddenly looking at raising their water and sewer rates 200%, 300% or 400%. These increases not only put a burden on the rate payers, they can make the town uncompetitive. In the struggle to hang onto population, officials are keenly aware of anything that might drive people away, including the cost of utilities. Small communities will sometimes put off maintenance because of concern about an increase in water rates, the PCA’s Dunn says.

And once the infrastructure is built, maintaining water and wastewater infrastructure can be a very expensive commitment for small communities, says Craig Johnson, an intergovernmental affairs staffer specializing in land use, environment, and energy for the League of Minnesota Cities. Cities should estimate the cost of ongoing annual operations and maintenance of a wastewater treatment facility to be 10% of the initial cost of the project, Johnson says. Cities are then also expected to set aside funds for planning and future upgrades.

Each year the Minnesota Public Facilities Authority receives funding requests totaling about $200 million for wastewater facilities and $100 million for drinking water facilities, says PFA executive director Jeff Freeman. These requests come to about twice as much as what the state receives from the federal government for the Clean Water and Drinking Water revolving loan funds. The state supplements the federal funds with its own matching funds (an 80% federal, 20% state split), plus funds from loan repayments and from bonding. For the funds’ lending capacity to become sustainable, federal and state funding need to remain at current levels, Freeman says.

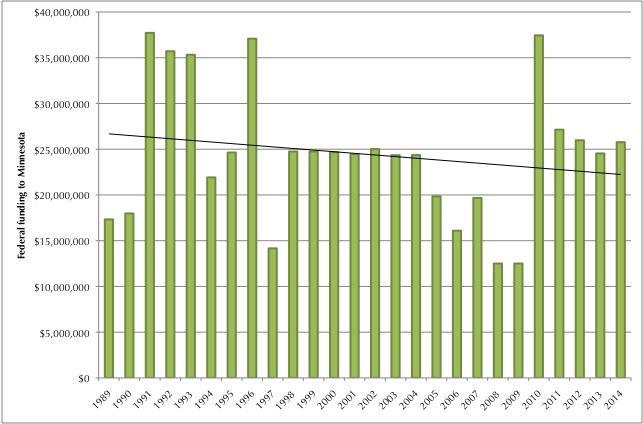

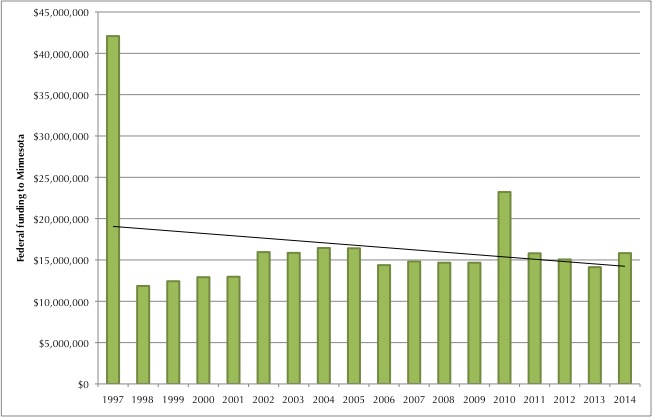

A look at federal funding levels, however, shows that while dollars for two of the largest federal infrastructure loan funds, the Clean Water Loan Fund and the Drinking Water Loan Fund (funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), has gone up and down a great deal in the last 25 years, the trend overall is downward.

USDA Rural Development is the other major funder of water and wastewater projects to rural areas. The amount the Minnesota office gives out in loans and grants each year varies considerably depending on how much money is appropriated to the state and whether there are other opportunities for funding, such as unspent funds available from other states.[10]

Does the current system encourage crisis thinking?

The PCA’s Project Priority List, while very good at what it does, ranks communities by level of crisis, which “promotes waiting until the entire system fails so a project is large and needy enough to be eligible for sufficient state and federal grants to become affordable,” says Dan Folsom, president of Design Tree Engineering in St. Cloud.

The PFA’s Jeff Freeman says that’s not quite true. The priority list’s ranking system is more complicated than that, he says, but it does in a way favor new treatment plants over routine maintenance, and grant dollars are limited ($11 million this year), meaning the farther down the list a city finds itself, the less likely it is to receive grants. Really small cities need all the supplemental grants they can get, Freeman says.

Much of the crisis feeling could be avoided through better planning. Asset management planning and capital infrastructure planning are tools that can show cities what they have now, what they will need in the future, and when they will need it, giving them the ability to understand and anticipate future costs. Developing a plan allows the city to get the maximum useful life out of its infrastructure. Oftentimes, when one thing breaks, a city will want to replace the entire system when it isn’t necessary, Freeman says. An asset management plan would break the system down into more affordable stages. “The idea is to encourage cities to plan ahead before there’s a crisis.”

Lewiston and Two Harbors are examples. Both were looking at options that involved larger, much more expensive replacements of systems. By working with their engineers and state agencies, they were able to come up with solutions that cost far less.

Planning could also reveal alternatives to the way things have been done. Cities are becoming more interested in sharing drinking water facilities, says Hubbard of the Minnesota Rural Water Association. While regionalizing wastewater facilities isn’t as practical, says Freeman, “we need to encourage cities to look at options for fixing existing septics rather than building a publicly owned system. Once you get one, you’re in it for the long haul.”

At the level of the individual small city, however, there is not a lot of comprehensive planning going on, and there are not many places cities can turn to for help, says Freeman. Planning costs money, and cities can be reluctant to take that cost on, even though there are grants and loans available to cover it and it may mean cost savings in the long run.

While all water issues are local, the consequences are statewide

In the 1980s the state made a concerted effort in funding and construction to get rid of combined sewer overflow systems around the state. These systems, common before the 1950s, combined the run-off of stormwater with the movement of wastewater. As a result, during times of heavy rain, storm water would overwhelm the wastewater system, flushing the untreated waste out into the environment. According to the PCA, because of the campaign to replace these systems thirty years ago, combined sewer overflow problems are now relatively minor compared with the rest of the nation.[11]

How then can the case be made to legislators and taxpayers to take on a similar large-scale campaign to address water and wastewater needs, particularly in small rural communities, and the costs associated with it? One compelling thought is that while all water issues may be local, their impacts are statewide. Water treatment infrastructure is expensive, but so is the impact on the environment and quality of life for those living in the immediate area and those living downstream. If rural communities cannot afford to fulfill their basic municipal infrastructure needs, “residents will find other places to live,” says engineer Dan Folsom, specifically population centers, placing further strain on the urban and suburban infrastructure in those places. Loss of population and loss of business means loss of tax base to an otherwise viable community, which in turn means loss of revenue to the state.

Considering the hurdles small communities face and the consequences both economically and environmentally when their systems are allowed to fail, the discussion on water begs a couple questions:

Is it time to invest again in an overhaul of the way we handle water and wastewater infrastructure in Greater Minnesota—particularly in how it’s funded? If so, who has the will to lead the way?

Recommendations to the Legislature:

- Re-establish the Legislative Water Commission and ensure it includes rural representation. There is movement at the State Legislature to re-establish the Legislative Water Commission. The issue of water in Minnesota is too complex, too important, and too expensive for legislators to make decisions based on too little information. A commission dedicated to studying water issues would be able to pull together the volumes of research data produced by state agencies and properly educate legislators on the issues before they come up for votes. However, given how the water situation differs around the state and the amount of infrastructure in Greater Minnesota, any commission or similar group must include rural representation, including by individuals who understand the unique circumstances of small communities in rural areas.

- Recognize that regulations and standards are needed to protect our water resources, but changes in these regulations and standards can come at a significant cost for small communities. The PCA must follow the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in setting standards and regulations for water quality, which impacts potential sources of point and non-point source pollutants such as businesses and farmers, but also wastewater treatment facilities. As standards change, usually in the direction of tighter regulations, communities are expected to upgrade their facilities accordingly. These changes can comprise a significant portion of a small city’s budget, and cities may be required to upgrade their infrastructure before they have finished paying off the previous project. While we do not advocate that smaller cities be allowed to operate at lower environmental standards, policymakers should take into consideration that these changing regulations can create a substantial burden for small communities.

- Start a discussion on whether long-term planning can help the smallest communities manage their infrastructure needs and costs. Should long-term planning be made a higher priority in small cities? Should we be considering regional planning in Greater Minnesota? There are several organizations already trying to help cities with planning, including the Minnesota Rural Water Association and West Central Initiative. A healthy discussion on the pros and cons of long-term planning with the right practitioners should reveal whether cities should pursue this and how to encourage it without creating more costly mandates.

- Support state agencies in sharing research and information that helps us all understand better the future of water in Minnesota. Given the stress we’re already seeing on the state’s water supply and given the expected trends in population growth, our state agencies involved in protecting the state’s water need and want a better understanding of just what is going on out there. While they do communicate and collaborate now, more is better. Agencies should be supported in their efforts to monitor water usage, their search for best practices in areas like conservation and technology, and their ability to share that information with each other.

- Be aware of and prepared for federal funding for rural projects to continue going down. Appropriations for some of the larger funds for rural projects have been trending downward slowly but steadily. State lawmakers should be aware that this will have have a significant impact on funding for water-related infrastructure in Minnesota and as a consequence, development in rural communities.

- We don’t necessarily have to pull the plug on some small towns. The question permeating the discussion on water and wastewater is whether we as taxpayers should continue to support water/wastewater infrastructure for the very smallest towns. It is hard to admit, but there are some towns that do not have a realistic chance of growing. However, it does not have to be an all-or-nothing future for them. There are alternatives to a traditional full-scale wastewater treatment facility. Encourage state agencies like the PCA and the PFA to continue working with the smallest communities and their engineers to explore these alternatives first.

To Learn More: For more information on helpful web sites and reports.

[1] Halstead, J.M., Deller, S.C. Dec. 2009. “Public Infrastructure in Economic Development and Growth: Evidence from Rural Manufacturers.” Journal of the Community Development Society, 150.

[2] The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency surveyed a total of 802 communities for its 2014 WINS report; 690 were outside the Twin Cities seven-county area. Of those communities, the PCA received 558 responses from Greater Minnesota. Out of that pool, 460 of them reported operating their own wastewater treatment facilities. The rest were either part of a larger sanitary sewer district or did not have a wastewater treatment facility or chose not to answer those questions.

[3] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, “Ground water provinces.” http://dnr.state.mn.us/groundwater/provinces/index.html

[4] Minnesota Climatology Working Group, “Ground Water Level Data Retrieval.” http://climate.umn.edu/ground_water_level/

[5] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, “Water Use Permits,” http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/watermgmt_section/appropriations/permits.html

[6] Minnesota Public Radio, “Unchecked irrigation threatens to sap Minnesota groundwater,” April 7, 2014. http://www.mprnews.org/story/2014/03/31/ground-level-beneath-the-surface-permits?from=hp

[7] Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2014 Wastewater Infrastructure Needs Survey, p. 26. http://www.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/view-document.html?gid=20506

[8] Populations couldn’t be determined for four of the projects.

[9] Minnesota Public Facilities Authority, “Infrastructure Funds and Programs.” http://mn.gov/deed/government/public-facilities/funds-programs/index.jsp

[10] The amount of dollars appropriated from Washington to Minnesota over the years wasn’t available at release time, but will be included when it does become available.

[11] Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2014 Wastewater Infrastructure Needs Survey, p. 22. http://www.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/view-document.html?gid=20506