Demand for nursing facility beds is growing while the supply is shrinking

November 2024

By Kelly Asche, Senior Researcher

Click here for a printable version of this report.

All of us are guilty, at one point or another, of taking our health for granted. We lean into the belief that we will always be able to take care of ourselves or our loved ones until the very end. Statistically, however, this type of situation isn’t likely. Many Minnesotans will need to use some form of professional long-term care, either through agencies providing home health care or by taking up residence in an assisted living or nursing facility. The long-term care industry is critical for providing care to our loved ones when their needs surpass what a family member can provide.

So it’s concerning when more and more stories are being told about elderly individuals not being able to access the care they need. We are hearing frequently from rural leaders and residents that access to home care is becoming difficult, assisted living may be too expensive if it even exists in a rural area, and that nursing facilities are either shrinking the number of beds they have available or closing completely.

This report focuses on bringing these stories from being not just anecdotes but to being facts by using the Department of Health’s provider data (helpfully provided by the Care Providers of Minnesota). The statistics are quite clear: the number of beds in rural licensed nursing facilities (commonly referred to as nursing homes) has declined between 30% and 100%, depending on the region, since 2005. Many of these declines are due to facilities closing and not just operators shrinking the number of beds available. And all of this is happening while demand for these beds is increasing and is expected to keep increasing until 2045.

The reason for these declines are two-fold:

- A long-time shift in consumer preference for alternatives to nursing facilities, which led to policy and financial shifts allowing home-care agencies and assisted living to take a larger portion of the elder care pie, and

- A more recent, severe shortage in staffing.

This perfect storm threatens to leave rural areas underserved. Not only is nursing facility capacity shrinking at a higher rate in rural areas compared to larger population centers, there are significant differences in the supply of assisted living beds and home care agencies as well.

This report is the first report addressing a research theme the Center for Rural Policy and Development will be diving into over the next few years: “Remaining resilient in an aging, rural Minnesota.” It will put numbers and context to this issue, setting it up for discussions on solutions later.

Demand for nursing facility beds is increasing and will vary across Minnesota

In 2024, the oldest members of the Baby Boomer generation turned 75. In the healthcare industry, this is a significant milestone. It’s a reminder that demand for long-term care among our elderly population is going to skyrocket over the next 20 to 30 years.

However, demand for these beds will not peak at the same time across all of Minnesota. It will actually peak much sooner in rural Minnesota, largely due to the older average age in rural areas.

To estimate peak demand, we used the 2023 Profile of Older Americans,[1] which provides the percentage of the U.S. population age 65+ being cared for in nursing facilities.[2] The data broke down this way:

- 65 to 74, 1%

- 75 to 84, 3%

- 85+, 8%

Applying that to Minnesota’s population projections provided by the Minnesota State Demographic Center,[3] we can see that demand will increase significantly statewide until about 2045. It’s estimated to peak in 2047 with an estimated 37,234 individuals needing nursing facility beds. Demand plateaus from there until 2055 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Demand for nursing facility beds is projected to increase significantly until 2040, when it will begin to plateau, then peak in 2047 and gradually decrease. Data: Profile of Older Americans; Minnesota Demographic Center Population Projections

If we break the data down across rural-urban categories based on population density, however, demand looks very different. Figure 2 shows that entirely rural counties will be experiencing peak demand significantly sooner than other county groups: 2037 compared to 2047 and 2055 in the other county groups.

Figure 2: Entirely rural counties will experience peak demand for nursing facility beds among population 65+ significantly sooner than other county groups. Data: Profile of Older Americans; Minnesota Demographic Center Population Projections

Figure 3 shows that the counties in the northwest and southwest corners of the state will experience peak demand for nursing facilities significantly sooner than the rest of Minnesota. These counties are estimated to have peak demand between 2025 and 2030, while other rural regions of Minnesota will peak five to ten years later, 2040 to 2045.

Figure 3: Northwest and Southwest Minnesota are estimated to experience peak demand for nursing facility beds about 10 years before the rest of the state. Data: Profile of Older Americans; Minnesota Demographic Center Population Projections

This means that rural areas have much less time to make changes in their capacity to serve their elderly population, but any changes will be difficult given the trends occurring in nursing care facility capacity.

Declining capacity in nursing facility beds

While the number of available nursing facility beds has been declining across Minnesota, the reasons why vary between rural and urban Minnesota.

Figure 4: The number of nursing facility beds has declined by a third since 2005. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

As of February 2024, Minnesota had 33% fewer nursing facility beds compared to 2005 (Figure 4). This decline isn’t consistent across the state, however. The most severe drops have occurred in rural Minnesota, where entirely rural counties have 41% fewer nursing facility beds compared to 2005, followed by 40% in town/rural mix counties, 33% in urban/town/rural mix counties, and 29% in entirely urban counties.[4] Figure 5 shows how this loss has progressed over the last twenty years.

Figure 5: The declines of nursing facility beds have been more severe in rural Minnesota. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Figure 6 shows where the most severe declines are currently happening: in northwest, southwest, and the north central lakes region of Minnesota. Red Lake County experienced the most severe decline – they lost all of their nursing facility beds since 2005. This is followed by Cass County—in 2005 they had 489 nursing facility beds, but by 2024 only 33 remained—a loss of 93%. Several other counties aren’t far behind, including Grant County (-75%), Swift (-69%), and Pine (-65%). Chippewa County is the only county to have more beds in 2024 than in 2005, due only to a new nursing care facility built by the Minnesota Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Figure 6: The largest declines in nursing facility beds are spread across Greater Minnesota. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Closures versus shrinkage

Although capacity has been decreasing across all of Minnesota since 2005, the loss of beds isn’t evenly distributed and neither is the cause of that loss. Besides the loss of beds, there is the loss of the facilities themselves. Entirely rural counties had 26% fewer nursing facilities in 2024 compared to 2005, while entirely urban counties were down by only 9% (Figures 7 & 8).

Figure 7: The decline in the number of nursing homes becomes more severe as the county group becomes more rural. Entirely rural counties have lost 26% of their nursing facilities since 2005. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Figure 8: Half or more of the nursing facilities have closed across much of greater Minnesota. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

This is important because, within the nursing facility issue, the loss of beds isn’t always caused by a facility closing. A nursing facility struggling financially also has the option to reduce costs by “unlicensing” a portion of their beds, essentially reducing their capacity.

But whether beds are lost because the facility closed or those beds were just unlicensed can affect a region’s ability to add beds in the future. A skilled nursing facility that has unlicensed capacity can reopen all or some of those beds again if circumstances warrant, but if the facility closes, those beds are lost. The data show that in rural areas, a larger share of the decline in beds is due to facilities closing. In fact, 58% of beds lost in entirely rural counties was due to facilities closing compared to a little over 40% in the other county groups (Figure 9).

Figure 9: A larger share of the decline of nursing facility beds in our most rural counties is due to facilities closing rather than shrinking. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

The map below shows that many counties scattered throughout rural Minnesota lost 50% or more of their beds due to facilities closing (Figure 10). Red Lake County lost all of their beds when one facility closed—as of 2024, there are no beds available in that county. Other notable counties include Nicollet, Lyon, and Kandiyohi, which lost over 95% of their beds from closures.

Figure 10: Over half of nursing care bed decline in many rural Minnesota counties is due to facilities closing. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Long-term and short-term factors converge

If demand is increasing, why then are facilities closing and/or shrinking their capacity?

The decline in nursing care capacity, both in terms of beds and facilities, has been driven largely by two factors, each with their own timeline in terms of impact:

- Long-term impact: a shift in consumer preference away from nursing facilities as technological, financial, and policy advances have allowed home-based care and assisted living to take bigger pieces of the elder care pie.

- More recent impact: Workforce shortages.

Historical challenges have caused declines, shifts in consumer preferences

In the 1970s and ’80s, nursing facilities played a much larger role in the physical and mental healthcare industry. In the past, nursing homes were the only option for post-surgery rehabilitation, care for individuals with dementia and less severe physical disabilities, and for people with mental disabilities.

However, that began to change in the early 1980s with the growth in assisted living communities and home- and community-based care agencies. Research attributes this growth to some key factors:

- A growing negative perception of nursing facilities among consumers starting in the ’80s and ’90s.

- Technological, policy, and payment shifts that allowed assisted living and home-based care to play a more prominent role in long-term care.[5]

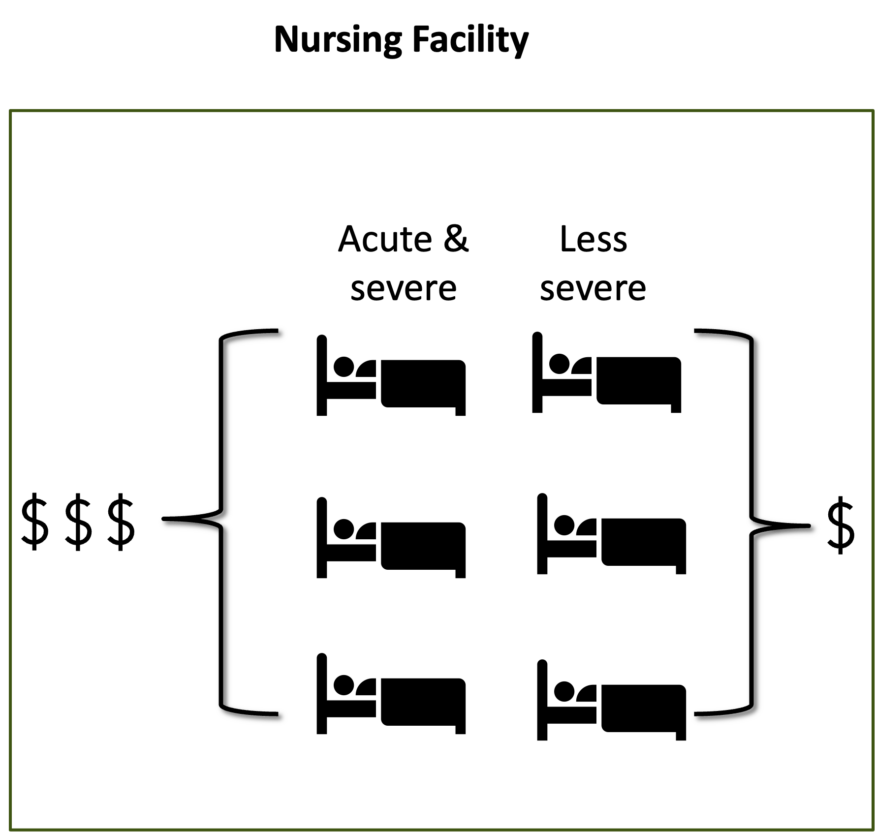

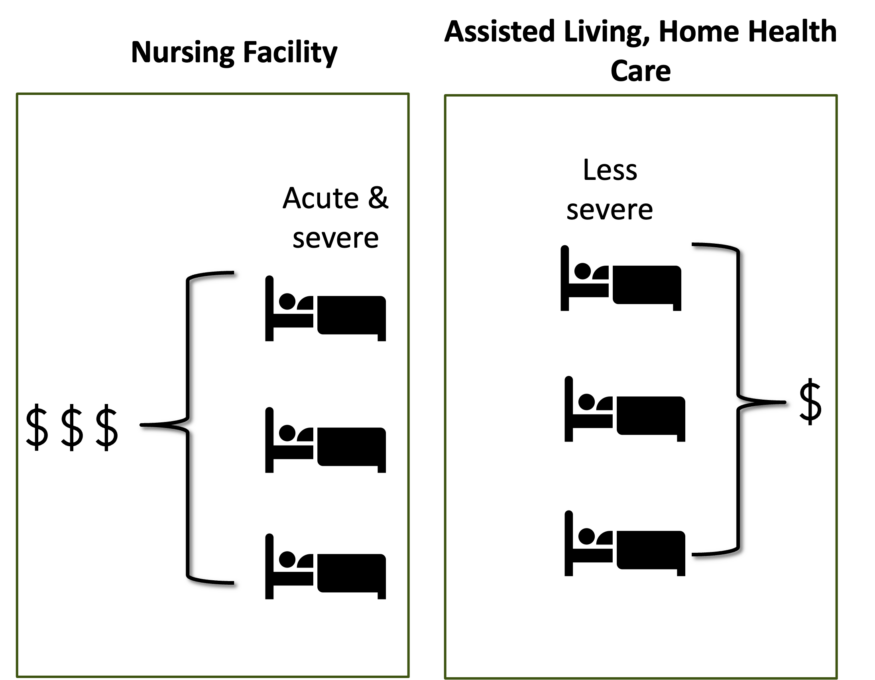

This combination of factors likely decreased demand among nursing facilities’ earlier consumers throughout the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s, leaving mostly people with the most acute issues. Unfortunately, caring for the most acute patients is an expensive business model, and, according to nursing facility operators, reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid haven’t kept up with the cost. In addition, nursing facilities in Minnesota are not allowed to charge more to privately insured patients (unlike assisted living facilities) to help make up for some of the financial loss from inadequate reimbursements.

Figure 11 provides a very simplistic view of the shift. Skilled nursing facilities used to serve a larger portion of the long-term care population—individuals with acute and chronic illnesses and individuals with less acute illnesses (on left). Less acute cases cost less to care for, allowing facilities to manage their costs across a variety of patients, balancing out profits and losses. Now that the patient pool is split among the various long-term care providers, most of the patients cared for by nursing facilities are the most severe and most expensive to care for (right image).

|

|

Figure 11: A very simplistic representation of the shift in the types of patients cared for by nursing facilities over the last 30 years.

So not only have nursing facilities experienced a shift in the overall makeup of their patients, but that shift has impacted revenue and expenses, making it more difficult to cover increasing costs. Todd Berstrom, Director of Research and Data Analysis at the Care Providers of Minnesota, said, “It used to be common that there were individuals staying at nursing homes that would still have drivers licenses and were still mobile. Now, it’s not uncommon to walk into a nursing facility and everyone needs a wheelchair.”

All of this is leading nursing care operators to look for economies of scale to make their business model work, a difficult proposition for small rural facilities. Figure 12 shows the licensed bed capacity of every facility that was open in February 2024 for each rural-urban county group. The light red line going across the chart is the average bed capacity of facilities that have closed in Minnesota since 2005, while the dark red is the median bed size of those facilities. The chart shows, unfortunately, that the more rural a nursing facility is, the more likely it is to be small, and more likely to be similar to the average size of facilities that have closed. That’s concerning for the future sustainability of rural facilities.

Figure 12: Each dot represents a facility located in each of the rural-urban county groups. The dot’s location on the y-axis is the licensed bed capacity for that facility. The light green and dark green lines represent the mean and median capacity, respectively, of the nursing facilities that have closed since 2005. Data: Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Interviews with nursing care operators in rural Minnesota also highlighted the challenging business model facing these facilities. Kari Swanson, CEO of Cornerstone Nursing and Rehab Center serving Bagley, Fosston, and Kelliher says, “Cost of supplies are up, wages are up, but payments have not increased enough… Lots of rural facilities are small and can’t scale down enough to make the finances work.”[6]

It’s worth noting that this shift to more acute care isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The change in consumer preferences helped create the assisted living and home-based care industry, which research has shown to be a better fit for individuals with less severe or chronic conditions.

The problem is that nursing facilities still play a vital role in long-term care, but their sustainability is in question due to the lack of diverse revenue streams to help cover the high costs of providing healthcare to more severe patients. It’s a problem all across rural Minnesota: economies of scale can be a nemesis when attempting to reduce costs. However, on top of this is an even more severe issue that has grown over the last ten years and entered crisis mode during the pandemic: workforce shortages.

The other challenge causing declines: Workforce Shortages

The most common challenge brought up by nursing care facility operators is their inability to find workers. For many, it’s getting to be a crisis: one nursing home operator said, “We are screening patients to make sure we have the workforce to meet their needs, and we are turning people away daily due to the lack of workers.”

It’s well known now that workforce shortages are a big issue in rural Minnesota across all industries and occupations. The shortage is particularly acute in healthcare, and unfortunately, skilled nursing facilities are feeling the pinch. Figure 13 shows the number of job vacancies in three occupations related to nursing home care: registered nurses, nursing aides, and personal care aides. Since 2012, the number of vacant positions has increased significantly across Minnesota. Vacancies shot up during the pandemic and have since recovered a bit, but the vacancy numbers are still very high across Minnesota. In rural Minnesota, the number of job openings in these occupations makes up between 10% and 15% of job openings across all occupations.

Figure 13: The number of job vacancies in the registered nurse, nursing aide, and personal care aide occupations. Data: MN DEED Job Vacancy Survey

Only part of the growth in job vacancies can be attributed to growth in demand for elderly care. A larger portion of the growth in vacancies are positions that were once filled but now sit unfilled. Greater Minnesota saw growth in occupations found in skilled nursing facilities—registered nurses, nursing assistants, personal care aides, and orderlies—from 2005 to about 2015, but that growth has since reversed (Figure 14). Our most rural regions of the state have only 25% more employment in these occupations than they did 20 years ago. And over the last ten years that employment has been declining due to the challenges in finding labor. This trend in demand for these services is just the opposite, however. Nursing facilities alone are expected to see demand for their services increase between 20% and 100% over the next ten years across rural Minnesota, as Figures 2 & 3 show.

Figure 14: Growth in occupations related to elderly care in nursing facilities grew steadily from 2005 to 2015 but has since been declining. Lines have been “smoothed” to show trends, not specific values. Data: MN DEED Occupational Employment and Wages.

Nursing care facility operators are trying many different ways to recruit more workers, including:

- Being more active in high schools to introduce these careers to younger people.

- Offering education incentives to individuals who want to become a registered nurse or other related licensed occupation.

- Pay increases and other monetary incentives.

But there are many factors that make filling these jobs particularly difficult. The primary issue is that rural Minnesota is facing a historic shortage of workers overall. To combat this, employers in other industries have been able to increase their pay, benefits, and other incentives, strategies many nursing facilities can’t compete with since their rates are locked in via Medicare, Medicaid, and state policy. In addition, small rural facilities struggle to improve their economies of scale to make more funds available for higher wages (refer back to Figure 12).

Especially challenging is the competition from other employers in the healthcare industry. Sometimes offering educational incentives only results in poaching when another healthcare employer can pay more once an employee finishes their schooling.

What many rural nursing facilities want is fewer barriers to providing service. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are implementing, in stages, new staffing minimums for nursing facilities. This could have serious ramifications for all nursing facilities, adding an additional challenge on top of current workforce shortages.

Anthony Shaffhauser from MN DEED is currently studying what this new directive would mean in terms of more pressure on an already strained workforce and whether nursing facilities would be able to continue to provide services. He was kind enough to share a draft of his report with the Center for Rural Policy and Development, and his numbers are alarming. Be on the lookout for his report, due in December 2024. Subscribe here to be notified when the report is published.

Another issue at hand is the Minnesota Nursing Home Workforce Standards Board, created by the state legislature in 2023. It was established to “conduct investigations into working conditions in the nursing home industry and adopt rules establishing minimum employment standards reasonably necessary and appropriate to protect the health and welfare of nursing home workers.”[7]

One of the sets of rules the board is statutorily obligated to examine is initial standards for wages (Minn. Stat. § 181.213 (b)). It is generally recognized that wages for workers in our nursing facilities are too low. Due to the way nursing facilities are paid and the extremely high costs to provide care, however, there is significant concern among nursing facility operators around how an unfunded mandate such as a minimum wage for skilled nursing facility workers would impact small rural nursing facilities’ ability to stay afloat, given their current lack of margin.

The role of non-institutional care

A primary reason for the loss in nursing facility beds is the larger role that assisted living and home health care are playing in providing long-term care. Compared to two decades ago, a significantly larger percentage of people who would have been living in nursing facilities are now living in other non-institutional facilities or at home.

In many ways, this has been a good thing. Research has shown that individuals with less severe ailments or less intense recovery reap many benefits from being cared for at home or in an assisted living facility, including cost and health outcomes. But the role of these types of facilities is limited and may not be what the patient needs in more severe cases, especially those needing 24-hour care, and there are significant concerns regarding access to these non-institutional care services in rural Minnesota.

Assisted living facilities

The State of Minnesota began tracking the capacity of assisted living facilities after 2020, so unfortunately we only have one year of data (2024). Although we know anecdotally that the number of assisted living facilities being built has grown substantially over the last ten years, we aren’t able to get exact numbers. A simple way to compare supply across rural and urban Minnesota would be to calculate the number of people age 65 or older per assisted living bed in that region. As Figure 15 shows, entirely rural counties have more than twice as many people age 65+ per assisted living bed compared to entirely urban counties.

Figure 15: There are 33 people age 65+ per assisted living bed in entirely rural counties compared to the much lower 15 in entirely urban counties. Data: MN State Demographic Center & Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Another way to look at it is whether assisted living beds can make up for some of the decline in nursing care facility beds. Again, this is not a one-to-one comparison since nursing facilities treat a very different population, but it can help us compare access to elderly care across rural and urban counties.

The chart below shows that in 2024, assisted living capacity in the entirely rural counties covered only 93% of lost nursing facility beds; in the entirely urban counties, assisted living made up for over 800% of that region’s loss in nursing facility beds.

Figure 16: The capacity for assisted living doesn’t even make up the loss of nursing facility beds in our most rural counties of Minnesota. Data: MN State Demographic Center & Care Providers of Minnesota; Minnesota Department of Health, Nursing Home Licensing

Home care

Currently, there is no public data available to measure the capacity in home care services. However, interviews with officials in the healthcare industry suggest that home care is facing challenges in keeping up with demand, too. Like any organization trying to provide services in rural Minnesota, it’s a difficult business model.

The table below provides a snapshot of the number of member agencies (there could be more non-members) providing home-based nursing care services in counties in the corners of the state, plus Carver County, representing the Twin Cities region.

Table 1: The number of home-based care agencies that are members of the MN Home Care Association providing nursing care services to selected counties. Data: MN Home Care Association Member Directory

Like nursing facilities, home-based care agencies struggle with economies of scale in rural areas, too. Staff must travel long distances to reach a few patients, increasing costs to operate, not to mention weather, which can make providing services an ongoing issue in winter.

In addition, rural patients are more likely to be on Medicaid, and Medicaid reimbursements don’t match the costs. Kathy Messerli, executive director of the Minnesota Home Care Association, says that one of her agencies estimates that they would lose $1 million annually if they only took on Medicaid patients.

Lastly, home health services face the same workforce shortage in rural areas when it comes to recruiting and retaining staff. To try to keep from losing people to hospitals, which pay more, home health care agencies may offer flexible schedules and other unique benefits.

It’s important to note that Table 1 doesn’t capture the individuals who provide nursing care themselves and don’t employ anyone else.

On the flip side, though, even if the agency is listed as providing services in particular counties, it may not currently have the staff to take on more clients. A number of interviewees told stories of people they know who are currently stuck in hospital beds because they can’t find appropriate services to care for them at home.

What to do?

The data presented demonstrates that the current supply of long-term care services, especially for nursing facility beds, isn’t likely meeting demand in rural areas now. The problem will only grow as demand for services increases over the next 20 years. Rural areas, with their larger senior populations, are going to feel the pinch first, which means they also have the least amount of time to prepare.

Every policy being discussed around long-term care must take into consideration the wide variety of facility capacity serving rural Minnesota and the geographic differences that affect the industry and its ability to operate. Raising standards and pay could help these facilities and agencies provide even better service, but the data show that these changes can’t be done based on the current business model. The economies of scale are such that without a large population to spread the risk over, long-term care facilities will only continue to struggle and close, leaving few options for rural residents.

Now more than ever it’s important to dig deep into this issue to find lasting solutions, both quick and slow, to address the barriers that are making it difficult for facilities and agencies to meet demand. The Center for Rural Policy and Development will be digging deeper into these specific issues to help provide further guidance and policy options over the coming year.

Bibliography

“2023 Profile of Older Americans.” Administration for Community Living, May 2024. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Profile%20of%20OA/ACL_ProfileOlderAmericans2023_508.pdf.

Lord, Justin, Ganisher Davlyatov, Kali S. Thomas, Kathryn Hyer, and Robert Weech-Maldonado. “The Role of Assisted Living Capacity on Nursing Home Financial Performance.” Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing 55 (August 24, 2018): 0046958018793285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958018793285.

MN State Demographic Center. “Data by Topic: Age, Race & Ethnicity.” ,. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://mn.gov/admin/demography/data-by-topic/age-race-ethnicity/.

[1] “2023 Profile of Older Americans.”

[2] Special thanks to Anthony Schaffhauser at MN DEED for providing guidance on these estimates. Look for his upcoming report diving deep into workforce shortages in the long term care industry being released in December 2024.

[3] “Data by Topic.” MN State Demographer

[4] These categorizations are from the Minnesota State Demographic Center explained in their report – “Greater MN: Refined and Revisited”.

[5] Lord et al., “The Role of Assisted Living Capacity on Nursing Home Financial Performance.”

[6] This quote has been updated from the original version.

[7] https://www.dli.mn.gov/about-department/boards-and-councils/nursing-home-workforce-standards-board