Limited resources are putting growing pressure on rural communities

May 2017

By Marnie Werner, Research Director

The mobile crisis and outreach teams of the Northern Pines Mental Health Center in Brainerd are busy. In 2016, they made 1,200 calls in the counties they cover—Aitkin, Cass, Crow Wing, Morrison, Todd and Wadena—and most of those calls were to emergency rooms at the counties’ seven local hospitals.

“That’s a lot,” says Northern Pine’s director, Glenn Anderson, more than Dakota County, which has more than double the population of Anderson’s six-county region, but Northern Pines has a good crisis response program, he says.

Other communities in Greater Minnesota aren’t as lucky. Mobile crisis teams are part of a continuum of care for people with mental illnesses called community-based services, and these services are vital to helping people manage their symptoms and recover from their mental illnesses. (Learn more about mobile crisis teams.)

As the name suggests, these services are offered through clinics and private offices in the community, where the person lives, rather than via an institution. Unfortunately, community services are inconsistent around the state, ranging from adequate to non-existent. No region is immune from a shortage in at least some services, forcing the people who need them to travel long distances or not access them at all.

Mental illness and how we as a society handle it is a sensitive subject. But even a quick look at the situation shows that lack of access to mental health care has real impacts. Without it, the seriously ill can find themselves debilitated, unemployed, homeless, in a revolving door of incarceration or worse. At the same time, first responders, hospitals, general practice doctors, families, teachers and employers are finding themselves increasingly on the front lines, confronting and trying to help those whose symptoms have gone out of control.

The fact is that we have a system that is incomplete, underfunded, woefully understaffed and unable to serve many of the people it is supposed to help, which in turn leads to higher costs for us all as we deal with the fallout in inappropriate ways.

“What we do have (in services) is pretty good, especially compared to other states,” says Sue Abderholden, director of the Minnesota branch of the National Alliance for Mental Illness, but those services aren’t consistently available or robust enough to meet demand.

The role of community services

There has been some improvement in recent years with increased funding, studies by two state task forces, some new innovative workforce programs and community efforts, but they have been mostly isolated fixes, according to those involved in mental health services.

From above, the mental health care system looks like a web of services covering the state, anchored by private, mostly nonprofit providers and a handful of state-operated facilities. The strands holding the web together are community-based adult mental health services, ranging from outpatient therapy to intensive residential treatment. (See here for definitions of the different community-based services.[1])

And these services are needed. It’s estimated that 20% of the population has some type of diagnosable mental illness, but only about half are receiving treatment. It’s also estimated that a large percentage of people in county jails (as much as 60%, says Abderholden) and people with substance abuse issues have mental illnesses that are likely diagnosable and treatable.

Until the 1970s, society addressed mental illness by housing people in institutions, or “mental hospitals.” At that time, the federal government began directing the closure of these institutions.

The plan was that instead of housing patients at large, distant, isolated facilities, people would instead be able to access the services they needed close to home through a network of community-based services.

Most Minnesotans with mental illnesses are much better off now than they were under the old system of large institutions, says Abderholden.[2]

The number of mentally ill patients in Minnesota’s state hospitals went from a peak of over 10,000 in the 1950s to less than 2,000 in 1980. By 2008 the state had closed all but two of its large hospitals, leaving only facilities at Anoka and St. Peter. Work started on community-based services in 1976, but in 1987, the Legislature put the responsibility for developing them on the Minnesota Department of Human Services and the counties.[3]

According to a report by the Office of the Legislative Auditor, though,[4] 30 years later, the web of services across the state still looks thin and inconsistent in many areas, with large gaps that the ill can easily fall through.

Spotty services in rural areas

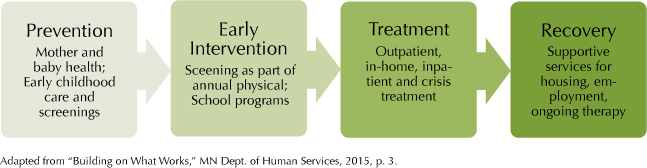

In general, about 3% of the population has a “serious” mental illness and about 2% suffer from a “serious and persistent” mental illness. Ideally, a person would seek care (fig. 1) early on, when illnesses are the most treatable. But at whatever point individuals enter the “continuum of care,” they would receive a combination of treatment and services to help them move through the stages of recovery.

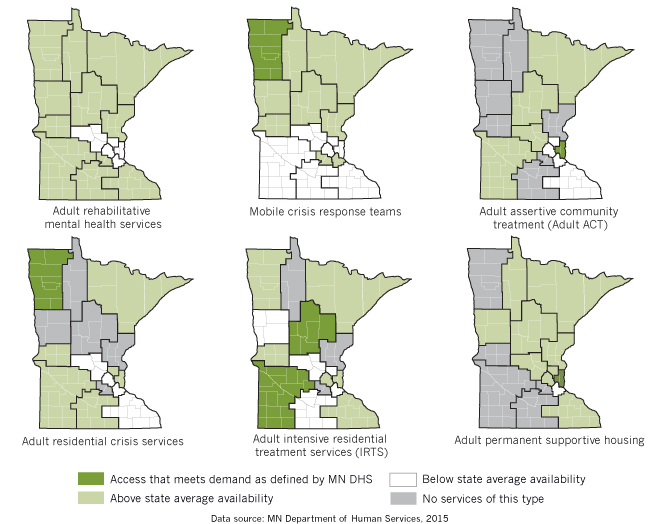

A 2015 report from the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) shows the spottiness of services (fig. 2). Looking at their availability by adult mental health service region (formed to help counties by pooling resources for more efficient service—fig. 3), no one region meets demand for every service,[5] and almost all of them are lacking in at least one critical service.

For instance, as of 2015, more than 50 counties had no permanent supportive housing for mentally ill adults, and nearly 40 had no adult assertive community treatment services.

Region Northwest 8, the adult mental health service region serving the counties in the northwestern corner of the state, had a level of access in 2015 that met demand for adult residential crisis services (a place where a person in crisis can safely stay overnight) and mobile crisis response teams, according to DHS. The region also had limited access to adult rehabilitative mental health services and adult intensive residential treatment services, but no access to adult permanent supportive housing services or assertive community treatment services, where health care professionals treat a person at home, making a hospital stay unnecessary. (Things may have changed since 2015.) Every region has similar gaps in services.

Services for children are even rarer. “In outstate, you have to start talking about the sparsity of providers, about how far away they are, how far parents have to drive, especially up north. The question then is how to make sure (children) and parents get there,” says Tom Delaney, supervisor of Interagency Partnerships in the Special Education division of the Minnesota Department of Education.

Minorities and immigrants face even larger barriers to services.

“Cultural communities are diverse—their faith, their values may be different from ours,” which can make these groups difficult to reach, says Louisa D’Altilia, senior director for Behavioral Health Services at Lutheran Social Service, which provides mental health counseling services around the state.

Minnesota needs to create diversity in its mental health system, but it’s slow to happen, D’Altilia says.

The rural conundrum: An unsustainable business model

While the problem in urban areas is not enough services for the volume of people, in rural areas the issue is not enough services because of a lack of people.

“One of the biggest challenges is viability for providers,” says Eric Ratzmann, director of the Minnesota Association of County Social Service Administrators. Counties are responsible for ensuring services are available, especially to those who do not have insurance, but they are not required to provide the services themselves.

“It’s hard (for counties) to set up contracts with providers if there’s no one there to contract with—if the provider can’t develop a viable business model for that area,” says Ratzmann.

The six north central counties forming Region 5+ contract with Northern Pines, which is working on becoming a full-service provider for the region. “It’s a neat trick when you don’t have a big population center,” says Anderson.

And herein lies the problem at the core of providing services in Greater Minnesota.

Sparse populations, the stigma of mental illness, long distances between communities and the resulting transportation difficulties in rural areas all contribute to fewer people seeking treatment. Fewer patients mean fewer services provided and therefore fewer reimbursements from insurance companies and Medicaid, leading to less revenue overall and less money to provide a full array of services.

In 2014, Riverwood Centers, which operated five clinics in five east central Minnesota counties, closed abruptly after one of the counties opted not to renew its contract.[6] While the area had private mental health clinics, “Riverwood was more accessible, used sliding-scale fees and served the uninsured,” Minnesota Public Radio reported at the time. Counties had to scramble to find services for Riverwood’s 3,000 clients.

In the absence of services, clients either don’t get them or local hospitals become the catch-all in mental health care. “It’s the same problem when people without insurance get health care from an emergency room. They think it’s the only place they can go,” says Anderson.

“The most common source of mental health services in rural areas is the family physician,” says Mark Schoenbaum, director of the Minnesota Department of Health’s Office of Rural Health and Primary Care. “Lack of other mental health providers means the primary care physician and medical clinic are called on to treat most mental health cases. It creates workload issues, and many physicians feel they don’t have the expertise.”

As workforce shrinks, salaries grow

Nowhere does this revenue issue have a bigger impact than in the mental health workforce. A shortage of doctors, nurses and other staff has been developing in most health care fields for many years now, especially in rural areas. (See, for instance, The Coming Workforce Shortage and The Long-term Care Worker Shortage at ruralmn.org.)

In mental health care, it is approaching a crisis. The situation is considered acute for psychiatrists, psychologists and advanced practice nurses (APRNs) in all of Minnesota except the Twin Cities and the state’s southeast corner.[7] Psychiatrists and APRNs are especially important because they are the only mental health professionals able to prescribe medication.

It’s not easy to pin down just how many psychiatrists are currently practicing in Minnesota. As of April 2017, the Board of Medical Practice recorded 631 licensed doctors with a Minnesota business address listing psychiatry as their first, second or third specialty (although this does not guarantee they are working as psychiatrists).

The number of psychiatrists specializing in child psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry is much smaller: only 139 licensed Minnesota psychiatrists listed child psychiatry as a specialty, while 21 listed geriatric psychiatry and 18 listed a specialty in addiction psychiatry.

The clock is ticking. Nearly half of the psychiatrists responding to a 2011 survey by the Minnesota Department of Health were 55 or over and most were planning to retire in fewer than ten years.[8] Also in 2011, there were only 303 licensed advanced practice psychiatric nurses, and 57% of them reported themselves as over age 55.

The Northwestern Mental Health Center in Crookston is recruiting and hiring constantly, says Shauna Reitmeier, the center’s director, and they’re having a difficult time affording salaries that are rising as the supply of professionals shrinks. Other expenses, like insurance, are going up, too, all while reimbursements from Medicaid and private insurers stay almost level.

For example: At Reitmeier’s clinic, psychiatrists’ services are effectively reimbursed 30 cents on the dollar, which means that for every one dollar the clinic spends on services delivered by a psychiatrist, the clinic receives 30 cents in reimbursement. Other services that are not performed by a psychiatrist are reimbursed at about 70 cents on the dollar. The clinic makes up the gap in both cases with grants and donations.

The reason for the difference? Psychiatrists are generally the highest paid individuals in the clinic, have the most years of training and are in a very specialized field, and yet the services they provide are reimbursed at a rate not much different from other staff members.

People who started out wanting to work for organizations like Lutheran Social Service are being lured away by higher salaries elsewhere, which is creating an issue, says LSS’s D’Altilia, when it comes to maintaining continuity of services.

The Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development’s Employment Outlook data projects that between 2014 and 2024, the size of Minnesota’s psychiatric workforce would need to grow by 18% above what it was in 2014 to meet expected demand. However, to also fill in vacancies left by people exiting the workforce, including due to retirement, the growth need increases to 44%.

Residency and clinical opportunities, where doctors, nurses, psychologists and social workers receive their required supervised practice training, play a crucial role in the supply of mental health professionals. In 2015, 2,445 students applied for the 1,353 available positions in U.S. psychiatric residency programs, and 1,339 of those positions (99%) were filled.[9]

Residencies are also important in that students have a tendency to stay near where they served their residency. Hospitals need some incentive to provide residencies and other supervised training opportunities, however, says Teri Fritsma at the Minnesota Department of Health. For mental health providers who are not doctors (e.g., psychologists, counselors or social workers), supervision is generally not a reimbursable activity. Therefore, time spent by them overseeing a student means less revenue coming into the facility.

Impact on the community

This shortage of services and the people who provide them is having a very real impact on law enforcement, ambulance services and local hospitals as they are increasingly asked to deal with people with untreated or difficult-to-manage mental health issues.

One tricky aspect of treating mental illness is that many people are undiagnosed, and it can be hard to detect building mental health issues, says Schoenbaum. By the time a person has come to the attention of the police, the severity may be higher than it would have been with early diagnosis and treatment.

While data recording just how many police encounters involve mentally ill persons is hard to find, there is data on drug use and alcoholism, which go hand in hand with mental illness, say both Schoenbaum and Anderson. The Minnesota Department of Public Safety announced a record amount of drugs seized in 2016.[10] In addition, the Centers for Disease Control reports that while Minnesota’s population grew by 13% between 1999 and 2015, suicides increased by 67%, alcohol-induced deaths by 97% and drug-induced deaths by 286%, from 169 to 653.[11]

Law enforcement on the front lines

The intensity of the symptoms a person experiences with untreated mental illness can rise and fall over time. When severity spikes enough, it becomes a crisis, which can be anything from a deep suicidal depression to a full-on psychotic episode, where the person is reacting to things only he or she sees or hears. These situations can be extremely dangerous for both the person and those around him, as news stories over the last few years have shown. In these cases, the first call is generally to the police.

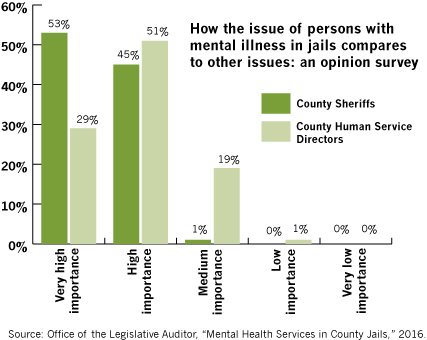

Law enforcement agencies are spending a growing amount of money on training in peaceful de-escalation methods, but once that person is under control, officers must decide what to do with him. In most parts of the state, according to the Office of the Legislative Auditor, they are pretty much limited two options: jail or the local hospital.[12]

If a law enforcement officer, family member or anyone else believes a person presents a danger to himself and/or others, the officer can take that person to an approved facility to have a qualified health care professional determine if the person should be held 72 hours for further psychological evaluation. In rural areas with few mental health care facilities and fewer open at night, and since injuries can be involved, the community hospital’s emergency department is often the most expeditious place to take someone for immediate evaluation.

Ideally, the hospital would have a psychiatric unit with staff trained to handle people who are out of control physically and emotionally, so if the hold is approved, the person would be admitted there.

If the hold is approved and the hospital does not have psychiatric beds or none available, it then becomes the responsibility of the law enforcement agency and hospital staff to locate a facility that can hold the person for further evaluation and stabilization.

That’s how it’s supposed to work. “There are statutes, and then there’s the reality of how those statues actually impact people’s lives,” says Angela Youngerberg, Director of Business Operations for Blue Earth County Human Services.

The reality is that law enforcement agencies are spending an increasing amount of time and funding on transporting people, sometimes for hours across the state or out of state to a qualified facility with an opening.

In 2014, there were 1,249 available psychiatric beds in Minnesota (not including Anoka-Metro Regional Treatment Center); 530 of those beds were outside the Twin Cities metro area, with 28% located in Rochester and Duluth alone. Only six of the state’s 79 critical access hospitals had any psychiatric beds (60 beds in total).

The problem, of course, is not only a lack of physical beds but a lack of personnel. A certain number of staff, depending on training and qualifications, can handle only so many patients safely.

Bed availability and transportation are huge issues, says Schoenbaum. To transport an acute case safely, the local ambulance and EMTs are often pulled in, too, putting pressure on small communities and counties with small forces and few EMT personnel.

“Safe, qualified transport is usually the ambulance. With the shortage of beds, the ambulance and its patient can be hours away from an available bed,” Schoenbaum says.

The Minnesota Hospital Association and the Minnesota Department of Health maintain an online directory law enforcement and health care staff can use to search for available beds online instead of making numerous phone calls. But once an available bed is identified, it may be on the other side of the state or in North or South Dakota, and even if the facility has an opening, it is not required to take in a new patient.

The Legislative Auditor’s report draws the connection between community services and the psychiatric bed shortage: “A state with strong nonresidential mental health services (such as mobile crisis teams) might need fewer inpatient beds…” [13]

According to a 2015 Minnesota Hospital Association report, a large gap exists in services especially for individuals with mental illness combined with violent and aggressive symptoms because of the limited number of inpatient beds in community hospitals, a lack of access to state-operated facilities and few community providers willing or able to accept these clients.[14]

Patients with difficult symptoms pose major problems for local hospitals that are not staffed or equipped to handle them, especially smaller hospitals. “(H)ospitals have reported instances of closing beds to additional admissions because of security concerns stemming from one patient on the unit,” MHA reported. “This means that other individuals cannot be served and staff may be at higher risk of injury.”

The Office of the Legislative Auditor’s report states, “One community hospital administrator told us … he has experienced significant staff turnover due to the hospital’s inability to transfer aggressive patients out of the hospital.”[15]

If a person is too aggressive when brought to the hospital or if he becomes aggressive while there, he may find himself in jail.

Unintended consequences: the 48-hour rule

An effort was made in 2013 to reduce the growing number of individuals with mental illnesses ending up in county jails by passing “the 48-hour rule.” The results, though, have only brought the shortage of resources into sharper focus.

Under the 48-hour rule, a person in jail must be moved to a state-run treatment facility within 48 hours of being found incompetent to stand trial, not guilty, or the charges dismissed for reason of mental illness. As of August 2015, nearly 85% of people being moved under the rule were being moved because of incompetency to stand trial.[16]

The 48-hour rule gives these individuals priority placement at a facility, and because of capacity issues or restrictions at other state-run facilities, the Anoka-Metro Regional Treatment Center has become the default facility for 48-hour transfers.

The trouble is that community hospitals are trying to get their difficult patients into AMRTC at the same time. AMRTC takes people on civil commitment who don’t warrant the “mentally ill and dangerous” designation that would send them to the St. Peter Security Hospital, but who have some type of high need or acute disorder, says Blue Earth County’s Youngerberg.

And as the line of patients gets longer, AMRTC has been operating well below its 175-bed full capacity (110 beds in 2015) because of staff shortage. From 2013, when the 48-hour rule was enacted, to 2015, the median number of days a person had to wait—usually at a community hospital—to get into AMRTC went from 33 to 53.[17]

Once individuals at AMRTC receive treatment and no longer require its high level of care, they can be sent home, provided community services like assertive community treatment, supportive housing, and transportation are available there to support their recovery.

A lack of community services at home, however, means the individual is not allowed to leave AMRTC and thus continues to occupy a bed that could be used for someone who does need to be there. This situation accounted for 35 percent of the center’s patient days from January 2014 to mid-2015, according to the Legislative Auditor’s report.

These delays now cost counties. In 2015, the Legislature began requiring counties to pay for the full cost of a patient’s care at Anoka for every day after the person was determined to no longer need hospital-level care. In 2016, CBHHs were added to the list. For fiscal year 2017, county governments are projected to spend $24 million on “medically unnecessary” days at AMRTC and state community behavioral health hospitals, says Eric Ratzman, director of the Minnesota Association of County Social Service Administrators. That’s as much as $1,800 a day per patient. The money goes into the general fund, where originally it was not designated toward anything specific. In the 2017 legislative session, however, policy was changed to dedicate some of those funds toward grants aimed at developing community services.

Working on solutions

To paint the whole picture of our mental health system is beyond the scope of this article, but it’s clear that it is a large, complicated issue, and it cannot be put right with quick fixes here and there.

However, there are many examples from around the state of how local providers are working to improve access to community services.

Yellow Line Project

Blue Earth County Human Services is working with the sheriff’s department and other law enforcement agencies to develop the Yellow Line Project, a jail diversion program that places a social worker “at the front door of the jail,” says Blue Earth County’s Youngerberg.

When a person with a mental illness is picked up by law enforcement, officers have few options, says Youngerberg, basically the emergency room, detox or jail. From the human services perspective, though, “there are lots of options. It’s a different way of looking at things.”

The social worker can contribute options on what would help and what’s available. Ultimately, it is the law enforcement officer’s decision to decide whether or not to divert from a criminal charge, but the discussion between the two disciplines makes for a more informed decision.

“With police and human services, the goal shouldn’t be to make one the same as the other,” she says. “They should work together.”

Interactive video

Interactive video technology is one of the most promising strategies for rural areas, where distance is a major consumer of time and money.

“It’s hard to have professionals on the road” visiting clients, says Dave Lee, Director of Public Health and Human Services for Carlton County. Those hours spent in the car could be used seeing more clients.

Carlton County is part of Adult Mental Health Initiative Region 3, comprising six counties and three tribes in northeastern Minnesota. The region covers 23% of the state’s land and only 6% of its population, so distance is the issue. The region is experimenting with the State of Minnesota’s internet-based telemental health system, Vidyo, to connect people with mental health providers.

For example, county jails sometimes have difficulty safely transporting inmates with severe mental health symptoms to a psychiatrist for diagnosis. The telehealth equipment installed in the jail allows the inmate to meet remotely with the psychiatrist, who can make a diagnosis and prescribe medication.

Schools in the region are also using the system, allowing kids to keep their appointments without the disruption of a long car trip, which can be upwards of 60 miles, Lee says.

“Patients are almost universally positive about it, and any resistance fades quickly,” says Lee. “It doesn’t replace face to face, but you can do more to help people when you have it.”

Childhood prevention and early intervention

School-Linked Mental Health Services already has a track record of improving access for children to mental health services.[18]

According to DHS, in Minnesota, mental health problems affect about 20% of children, and about 9% of school-age children have a serious emotional disturbance that interferes with their ability to function at home and at school.

The School-Linked Mental Health Services program funds the co-location of mental health services in local schools.[19] Community mental health agencies provide the staff at each school, who work directly with kids there.

The program has increased access to mental health services for children, especially those on Medical Assistance programs and those who had never accessed mental health services before.

Treatment courts

Mental health courts are one variety of treatment courts and are modeled after the state’s longer-standing drug courts.[20] Similar to drug courts, the idea behind mental health courts is to divert defendants with mental illnesses away from jail and into treatment and hopefully away from the cycle of behaviors that brought them to court in the first place. Mental health court is voluntary and invitation-only. Those who choose to participate agree to the conditions of community-based supervision. Court staff and mental health professionals then work together to develop individualized plans for treatment and supervision in the community.

While drug courts are more common, currently only Hennepin, Ramsey and St. Louis counties have mental health courts.

Certified Peer Specialists

Individuals who have experience with mental illness can receive training and be qualified as Certified Peer Specialists by DHS to work with individuals with mental illnesses, helping them discover their own strengths and work on recovery goals. CPS’s can work in a number of service areas, including assertive community treatment, crisis response and intensive residential treatment services.

Minnesota Management and Budget’s research into the cost-benefit comparison of CPS[21] showed a decrease in hospitalization and homelessness and an increase in employment and general functioning for individuals. Providers are optimistic about the CPS idea, especially as a connection to diverse cultural groups, but unfortunately it is difficult to find individuals who meet the present qualifications, MMB’s report stated.

“We’re not satisfied.”

Health care issues for rural people are everybody’s business, says Steve Gottwalt, president of the Minnesota Rural Health Association. “How can you accomplish anything else for economic development if you don’t have a healthy population with good health care? It’s everybody’s business to be concerned.”

According to Rep. Clark Johnson, who served on the Governor’s Mental Health Task Force, a lot of good things are going on to improve services for people with mental illness, “but we’re not satisfied, nor should we be. These are our family members, our neighbors, people we love.”

Recommendations

- See the big picture: Understanding the big picture is important and will help in understanding how potential solutions fit into the larger picture—and what impacts they may have in both rural and urban areas.

- Workforce is a top priority: Consensus among those interviewed is that workforce is the biggest problem, particularly the lack of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses (APRNs). Addressing workforce issues is crucial, especially in ways that bring workforce to rural areas.

- Dedicate funds: Counties—and county taxpayers—are required to pay for the medically unnecessary days people spend at AMRTC because of a lack of community services in their county, but these funds go into the general fund. It is important that they be dedicated to some purpose that improves community services.

- Build trust I: The mental health system involves many separate groups with different levels of knowledge, interest and trust, and some are only beginning to talk to each other. Be cautious of assuming everyone is in the same place, which will help with keeping the paths of communication open and constructive.

- Build trust II: In particular, while it was difficult to track officially, there was a perceptible level of friction between law enforcement and the mental health community, brought on by conflicting interests and regulations as the two groups tried to go about doing their jobs. Given the current state of the system, these two groups will continue to be thrown together. Some care can be taken to make their jobs easier by helping them work together.

- Diversity: Immigrants and refugees are a growing part of Greater Minnesota’s population. Long-term planning should include addressing their mental health issues, too, especially since many of them went through traumatic experiences to get here.

[1] MN Department of Human Services, “Understanding the Adult Mental Health Service Continuum,” 2015. http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/countyaccess/documents/pub/dhs16195685.pdf

[2] Des Moines Register, April 14, 2015. http://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/2015/02/14/minnesota-iowa-mental-hospitals/23430427/

[3] Minnesota statute 245.464; https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=245.464

[4] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[5] MN Department of Human Services, “Building on What Works,” March 2015.

[6] MPR, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2014/03/18/health/riverwood-centers-close; Minneapolis Star Tribune, http://www.startribune.com/minn-mental-health-center-shuts-down-stranding-thousands/250719041/

[7] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Building on What Works.”

[8] “Gearing up for Action,” Appendix A, 21. http://healthforceminnesota.org/assets/files/GearingUpForAction.pdf

[9] National Resident Matching Program, “Results and Data: 2015 Main Residency Match,” April 2015. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2015final.pdf

[10] Minnesota Department of Public Safety, March 6, 2017. https://dps.mn.gov/divisions/ooc/news-releases/Pages/record-amounts-of-drugs-seized-in-minnesota.aspx

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death database. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

[12] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[13] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016, 29. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[14] Minnesota Hospital Association, “Mental & Behavioral Health: Options & Opportunities for Minnesota,” 29. http://www.aha.org/content/15/minnmentalhealthwhiteppr.pdf

[15] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016, 31. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[16] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016, 91-92. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[17] Office of the Legislative Auditor, State of Minnesota, “Mental Health Services in County Jails,” March 2016, 31. http://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/2016/mhjails.htm

[18] Minneapolis Star Tribune. http://www.startribune.com/minnesota-sensibly-bolsters-funding-to-provide-expanded-services-for-kids/259462871/

[19] Minnesota Department of Human Services. https://mn.gov/dhs/partners-and-providers/policies-procedures/childrens-mental-health/school-linked-mh-services/

[20] Minnesota Judicial Branch. http://www.mncourts.gov/Help-Topics/Treatment-Courts.aspx

[21] Minnesota Management and Budget, “Adult Mental Health Benefit-Cost Analysis,” December 2016. https://mn.gov/mmb/results-first/