Ulises Linares, Zoe Martens, Kerim Örsel

In collaboration with: Dr. Greg Lindsey, the University of Minnesota Humphrey School of Public Affairs, and the Center for Rural Policy and Development

In 2021, the Center for Rural Policy and Development worked with students at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs to publish, “Building Community Embracing Difference,” which studied the relationship between local government outreach and equity and inclusion in four racially-diverse rural meatpacking towns. While last year’s report found that the relationship between trust, access to services, and community cohesion was strong, this year CRPD once again partnered with UMN master’s students to investigate childcare access barriers specific to rural BIPOC populations. CRPD’s most recent childcare report, “Childcare in rural Minnesota after 2020,” established that the rural childcare deficit is impacting employer’s ability to attract and retain their workforce. As such, immigrant access to childcare services is an important backbone of both social and economic mobility, and the rural economy.

The following report is an excerpt of significant findings from this most recent collaboration with the Humphrey School. For access to the full report including the literature review, methodology, and detailed analysis of findings, click here.

Trust, cost, availability, and information are top-of-mind for immigrant families seeking childcare

Limited access to child care in rural Minnesota is a well documented problem; however, immigrant communities face particular and compounded barriers to access. We explore the experiences of Latino immigrant families in the city of Worthington in Nobles County, a community rapidly diversifying in response to the needs of meatpacking employers. This report draws upon academic literature surveying child care deserts, immigrant access to child care, and the experiences of child care providers, in addition to original quantitative and qualitative research. GIS maps highlight the state of child care access in Nobles County in terms of geolocation, costs and capacity. Findings from 26 interviews with Latino immigrant families, child care providers, and local officials and administrators illustrate understandings of child care barriers, access and quality.

Analysis of US Census data shows that despite large parts of Nobles County having a provider nearby, capacity and cost often limit access. While Nobles County is a borderline child care desert, the city of Worthington is a child care desert under federal definitions. Further, child care costs exceed the affordability threshold of 7 percent of annual household income for the majority of the county. In Worthington, all census tracts with the highest childcare price burden correspond to areas with significant Latino populations.

Interviews with families, providers and officials highlighted 14 barriers to child care access, 9 of which fell into barriers already established in the literature, and 5 that were unique to this study. Of note, Latino immigrant families brought up barriers that other groups did not recognize, such as lack of access to information and the unknown safety of providers, suggesting different interpretations of barriers and trust across the 3 groups interviewed. Interviews also revealed some of the ways that Latino immigrant families access care in light of these barriers, and the ways they define quality care.

Interviewee profile

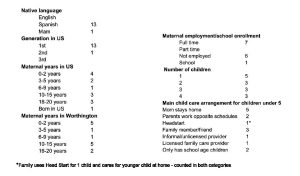

We conducted 26 semi-structured interviews (see Figure 3) with 3 groups that have distinct perspectives and experiences engaging with and overcoming child care access barriers. Immigrant families provided important insights about personal experiences using child care or

providing their own care. Child care providers shared varied experiences depending on the type of child care they offer, its level of formality, and their personal experiences interacting with children from different cultural backgrounds. Lastly, interviews with county officials at different service levels provided information about child care licensing processes, child care assistance, and policymaking.

In consultation with the Center for Rural Policy and Development, we decided to interview a higher number of Latino immigrant families than any other category of interviewees. We wanted to highlight the lived experiences of families, given the current lack of information regarding

Latino immigrant families’ child care experiences in Nobles County. In conducting this study we interviewed 14 1st generation immigrants families, 4 local government officials, and 8 child care providers in the county. The majority of childcare providers we interviewed were home-based family childcare providers.

We collected data over about two months, through virtual video or phone interviews of approximately one hour each. The interviews were in Spanish or English, depending on the interviewee’s preference. The audio of the interviews was recorded with informed consent from the participant and the interviewer took notes. The notes were then summarized into contact notes used for coding. A summary of the characteristics of Latino immigrant families interviewed follows.

Figure 1. Latino Immigrant Family Interviewee Characteristics

Nobles County is poorer, more Latino, than most of MN

The demographics of Nobles County highlight some of the challenges that immigrant families may face in gaining access to child care. Nobles County is a Southwestern county in Minnesota, characterized by a mix of city and rural areas (Center for Rural Policy and Development Rural Atlas). Nobles County and its largest city, Worthington, have a high concentration of Latino residents, foreign-born residents, and residents that speak a language other than English as compared to the 3 counties bordering it in Southwest Minnesota and Minnesota as a whole, as seen in the figure below.

Table 1. Nobles County Demographics

| Percent foreign-born | Percent Latino | Percent that speak a language other than English at home | |

| Worthington | 32 | 40 | 48 |

| Nobles County | 21 | 29 | 32 |

| Rock County | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Jackson County | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Murray County | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Minnesota | 8 | 6 | 12 |

Data: 2020 American Community Survey Since 2000

Nobles County’s population has been rapidly diversifying and the White population has been in decline (Minnesota Employment and Economic Development 2021). Nobles County is home to large employers like the JBS meatpacking plant and Highland manufacturing, as well as seasonal farm work, which attract many immigrant workers. Despite the presence of significant employers, Nobles County and the city of Worthington have lower socioeconomic status, as compared to its neighboring counties and Minnesota as a whole, as seen below.

Table 2. Nobles County Socioeconomic Status

| Median household income | Percent of people in poverty | |

| Worthington | $49,550 | 15 |

| Nobles County | $56,000 | 9 |

| Rock County | $65,744 | 8 |

| Jackson County | $62, 479 | 8 |

| Murray County | $62, 839 | 8 |

| Minnesota | $73,382 | 8 |

Data: 2020 American Community Survey

Nobles County’s childcare capacity desert

In our interview results below, limited childcare capacity is cited as a major barrier to childcare access by all three types of interviewees, which the quantitative data supports.

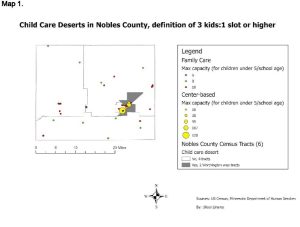

A given community is considered a child care desert when it meets a ratio of 3 children to every 1 childcare slot. Analysis of capacity data using census tracts and licensed providers shows that while Nobles County is a borderline child care desert, Worthington is, by definition, a child care desert (Table 3). Breaking the county down into smaller spatial units shows that Census Tract 1055 within Worthington has a statistically significant ratio of children to slots, illustrating that capacity challenges are not equally distributed across the county nor city.

Table 3. Worthington is a childcare desert

| Census Tracts | Children 0-5 | Childcare Slots | Children: Slots Ratio |

| Nobles County | 1869 | 678 | 2.8: 1 |

| Tract 1051 | 125 | 110 | 1.1:1 |

| Tract 1052 | 190 | 74 | 2.6:1 |

| Tract 1053 | 185 | 70 | 2.6:1 |

| Worthington* | 1369 | 424 | 3.2:1 |

| Tract 1054 (W)** | 524 | 173 | 3:1 |

| Tract 1055 (W) | 353 | 65 | 5.4:1 |

| Tract 1056 (W) | 492 | 186 | 2.6:1 |

*Estimate for Worthington from the sum of Census tracts within the city, as tracts do not align exactly with city boundaries. **(W) indicates Census tract overlaps with Worthington area; however, tract boundaries do not align with city boundaries and part of the tract may lay outside of Worthington boundaries.

Map 1 shows the child care capacity at the county level. The map reveals that on a Census tract level, 2 Census tracts in the city of Worthington are child care deserts, despite the fact that providers tend to be concentrated in the city. In contrast, none of the Census tracts outside of the city are considered child care deserts due to the lower number of children 0-5 residing in those tracts. Importantly, the 2 Census tracts which qualify as a childcare desert overlap with areas occupied by Latinos.

The data above shows that childcare capacity is a prominent barrier to childcare access for all families in Worthington, a fact which interviewees from all 3 groups reiterated. However, capacity challenges are not the same for all age groups. While finding open slots for infants might be extremely difficult as the number of infants that providers can care for at once is the most limited, providers may have multiple open slots for school-age children. For example, a family care provider who is licensed to care for up to 14 children at a time can have no more than 10 children under school age, and of these 10 children, no more than 4 can be infants and toddlers. Of those 4, no more than 3 can be infants. This is because child care licenses restrict the number of children providers can care for within the age categories of infant, infant and toddler, and children under school age.

Families echoed providers’ challenges with age-restricted capacity limitations and said that finding care capacity for infants was difficult. They struggled to find providers who would take infants across all types of child care providers- child care centers, licensed family care

providers, and informal providers. Families had particular capacity concerns with regard to informal care providers because, at one extreme, some informal providers cared for too many kids at once and at the other extreme, they could care for very few children due to constrained

living conditions, such as living in small apartments or sharing homes with other families. One mother commented on her experience considering informal providers, explaining that while some care for too many kids, the fact that others have very few kids in their care can raise concerns about the quality of their care, suggesting they were not a provider preferred by other families: “There are those that already have a lot of kids and can’t take more and those that have only a few kids- do I use them, do I not, or do I stop working?”

Barriers to childcare access for rural first-generation Latinos

Beyond capacity limitations due to Worthington’s childcare desert status, other barriers to childcare access discussed across all three interview groups include transportation, language, schedules, and immigration consequences. However, Latino immigrant families expressed some unique understandings of barriers, access and quality that providers and officials did not mention. Different interpretations of these themes have significant implications for the appropriate actions to address the child care crisis, and therefore, it is essential that Nobles County and Worthington respond to the lived experiences of Latino immigrant families to shape their response to the child care deficit.

Barriers to childcare access and the way that families navigate them often mean that Latino parents do not have access to care that they consider high quality, as they may face trade-offs between life circumstances like socioeconomic status and language ability on the one hand, and quality and licensure on the other. Our findings largely focus on these barriers, given this is a baseline study to start to understand the experiences of Latino immigrant families in Nobles County. While we also explore access to care and understanding of quality, limited time and resources mean that information on barriers has the greatest breadth and depth, and future research should continue to explore the elements of access and quality in immigrant families’ experiences with child care.

Our interviews revealed 14 barriers, 5 of which were mentioned by all 3 groups, 2 of which were mentioned by 2 groups, and 7 that only 1 group mentioned, illustrated in the following figure (Table 3). This summary of findings below will cover the 4 barriers mentioned by all interview groups beyond capacity limitations, and the 3 findings only identified in speaking with immigrant families. See the full report for a complete analysis of interview data.

Table 3. Barriers to Child Care Access for Latino Immigrant Families in Nobles County

| Latino Immigrant Families | Childcare providers | Local officials/administrators | |

| 1. Capacity | X | X | X |

| 2. Transportation | X | X | X |

| 3. Language | X | X | X |

| 4. Schedules | X | X | X |

| 5. Immigration consequences | X | X | X |

| 6. Bureaucratic burdens | X | X | |

| 7. Cultural preferences | X | X | |

| 8. Cost | X | ||

| 9. Lack of information | X | ||

| 10. Unknown safety | X | ||

| 11. Licensing process | X | ||

| 12. COVID-19* | X | ||

| 13. Location | X | ||

| 14. Limited Outreach | X |

*We asked providers directly about COVID-19 due to the challenges the literature describes for providers during the last two years, but did not ask these same questions to families and officials, meaning we cannot facilitate a direct comparison regarding COVID as a barrier

Transportation

Providers and local officials and administrators shared that, given capacity challenges, some families with multiple children have to distribute them amongst more than one provider. This brings with it further difficulties relating to transportation as the distance they are needing to travel in a single morning or evening is significantly increased. They have also highlighted the matter relating to the lack of transportation options families had and how it has made it additionally difficult for families to find ways of transporting their children within the city and county limits. However, families talked about their experiences with transportation barriers, not in terms of driving children to multiple care locations, but rather according to the mode of transportation they tend to use, informal ride services.

Most families interviewed did not have a car and/or lack the immigration status to obtain a driver’s license and therefore, pay others with access to these resources to drive them. This means that transportation to and from care can be an additional expense in terms of daily ride costs, something that middle to high-income families do not experience. Transportation to and from care also could be constrained by the availability and schedules of ride providers, as families pay to get rides to get to work along with others going to the same place, and detouring to drop kids off at daycare may not be feasible depending on other passengers’ work schedules.

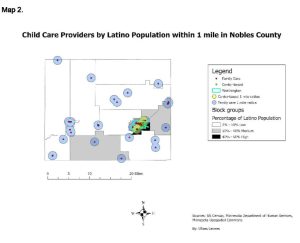

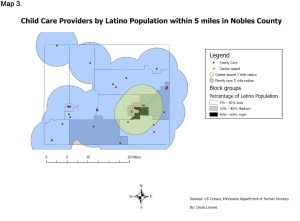

To deepen our understanding of potential transportation barriers, the following maps illustrate the geographic location of child care providers in Nobles County. Maps 2 and 3 show child care providers at the county level and the areas of the county within a 1 and 5-mile radius around their locations, respectively. While the majority of the county is within 5 miles of a provider, very select locations are within 1 mile, raising transportation issues. Further, even if a family is able to drive 5 miles to the nearest providers, this does not mean there is the capacity or that other barriers to care are not present.

Language

Language is another principal barrier to child care access that child care providers, local officials and administrators, and Latino immigrant families all mentioned. Considering nearly a quarter of the county’s population speaks Spanish at home (ACS 2020), the lack of Spanish language abilities among providers poses a challenge to the families when trying to find providers in their vicinity.

Only one family care provider spoke Spanish in addition to English, which highlighted language as one of the most prominent barriers. Providers recognized that their lack of language skills made them less accessible to Spanish-speaking families. On the other hand, while most local officials and administrators themselves did not speak Spanish or other languages, they pointed out their ability to access interpreter services, as well as members of their staff who speak Spanish to act as interpreters if needed. They indicated that although these methods can be useful, they still need to rely on an additional individual to communicate with families. Families shared their experiences navigating substantial language barriers. One mother explained that during her child care search, she prepared with her English teacher beforehand to try to communicate with monolingual English speaking providers, but still felt the language was a major barrier to securing good care for her daughter:

“She [the English teacher] wrote down the questions I wanted to ask, the possible responses and I was studying it for days before showing up. I was there, like maybe 20 percent clear, but I thought if they understood one word, that’s good. I always had a notebook with me where I wrote down words I heard to ask my teacher. It was very hard- I felt, I don’t know, sometimes I felt like I could cry in the line at work because I imagined my poor daughter there and I said, ay no.”

Another mother talked about language barriers as an immigrant whose first language is Mam, an indigenous dialect. For her, even if providers and county programs had robust Spanish language access, she would still lack access in her native language. She explained feeling intimidated by going to child care providers, since she does not speak English, does not feel confident in Spanish, and does not read. She summed up her hesitation to use services even where there is Spanish access based on her experience with Spanish-speaking service providers: “there are people who have patience and people who don’t.”

Schedules

Another major barrier posed is the discrepancy between the schedules of child care offered and families’ work schedules. Many families worked the first shift, which tends to start around 6 or 6:30 am. Some families worked first shifts in other communities, such as Windom, Minnesota or Lake Park, Iowa, which required up to an hour of commute time. One mother reflected on the relationship between being an immigrant and working shifts that make finding child care more challenging, stating: “most American people have more accessible work schedules and it’s more feasible to find care.”

Both providers and local officials and administrators were aware of the varying schedules families had due to their work hours. While providers indicated that they were willing to be flexible by 15 to 20 minutes with their drop-off and pick-up times, officials pointed out that adjusting drop-off and pick-up times by a few minutes is often not sufficient for work schedules and more drastic changes to the hours child care is provided would be necessary. In contrast to English-speaking providers, the Spanish-speaking informal care provider interviewed and the one Spanish-speaking family care provider reported 10 to 12-hour days, in an effort to accommodate the work schedules of their clients. They both reported accepting children starting at 5 am, aligning with the start times that most Latino immigrant families stated. However, this was a strain on the providers, posing a potential barrier to the sustainability of their businesses.

Immigration Consequences

A further barrier highlighted mostly by families and local officials is the potential for adverse immigration consequences as a barrier for families using care and related assistance programs. One mother reflected on avoiding the county due to its association with potential immigration consequences, stating, “when I looked for a babysitter for my daughter, no I never went to the county. Honestly, when Latinos hear ‘family services’, we enter in panic.”

Another mother had used a short-lived child care program through the Tri-Valley Opportunity Council and had partnered with staff to address this very barrier by reaching out to other immigrant moms in the community. She explained this was important “because you don’t hear about that [child care centers] a lot or it’s something new, so the moms were distrusting and they were like what? Is it true? And why?” As part of this program, families had to present pay stubs and other documentation to establish their eligibility, as the care was free and funded through a government grant that Tri-Valley had received. She stated: “people mistrusted that and asked why? Maybe they will get us in legal or immigration trouble and stuff like that.. it’s difficult- the fear invades us, that they will return us to our country.”

Providers did not talk about this barrier, with the exception of the one Spanish-speaking family care provider. She shared her experience offering care to undocumented immigrant families, explaining that despite her services being accessible due to her native Spanish skills and early start time, “when they realize they have to fill out an application with me, they don’t come back.” She explained further:

“I think the people without papers go with people without licenses- or with people who don’t ask for an application… I understand they are afraid and it’s easier for them to bring them to a person and it doesn’t matter if they have to pay a little more, they want to avoid filling out applications.”

Officials and administrators were almost all aware of the fact that Latino families were at the risk of putting their immigration status in jeopardy in a myriad of ways, from driving without a driver’s license to working without a work permit. They also mentioned the potential distrust immigrant families may have towards local officials depending on their immigration status, making it more difficult with regard to engagement and outreach.

Cost

Of the 3 groups interviewed, only families emphasized the prohibitive cost of child care. Families generally considered daycare centers the most expensive, as one mother interviewed considered these providers as “private,” meaning they had a higher price. They also reported that child care costs more for younger ages and becomes more of a burden when families have more than 1 kid. One mother commented:

“But in a daycare, it’s much more expensive…. I haven’t gone there because they charge a lot, but a woman told me she brings her child there and they charge $3 an hour, something like that- it’s a lot per week, only for 1 kid. And I have 4 no, I don’t know how much they’d charge!”

Child care costs for families also often include the price of rides that parents pay for in order to get to and from the child care provider. This is an added cost associated with child care, as parents have to consider the price of rides not just to and from work, but also dropping off and picking up their children each day. Families view these costs within the context of their salaries and it can be challenging to pay for care when it means that you only earn half your paycheck “because the other half goes to the babysitter.”

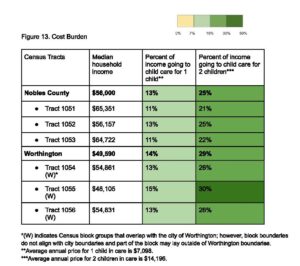

Figure 13 illustrates the price burden for families paying for child care across Nobles County, which is consistently far above 7 percent of annual household income that the US Department of Health and Human Services would consider affordable.

Lack of Information

Another prominent barrier named by families is lack of information. Many families had only general ideas that there were likely care providers and day care centers in the area, but were uncertain of their exact location or how the pricing worked. Lack of information was also often related to social isolation, as many mothers reported mostly staying at home, not knowing a lot of people and lacking information about the child care infrastructure in the US. One mother commented:

“Sometimes you don’t really get out much and you don’t know a lot about day cares…I never knew about a day care until after, when my son was born and I started going to the [early childhood education] school and there I learned more about day cares. Sometimes you don’t inform yourself.”

One area in particular where many families lacked information was the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), which has the potential to make child care more financially accessible. For nearly every mother interviewed, the interview itself was the first time they had heard of the program. This was especially striking because nearly every mother interviewed had received Women, Infants and Children (WIC) assistance through Nobles County, suggesting that they had children were born in the US and were income eligible for assistance programs, yet the vast majority did not know that CCAP was a resource available for their children.

Unknown Safety

Related to the lack of information and social isolation that many families experienced, families also reported the unknown safety of providers as a barrier. Many families worried about using care providers that they did not personally know or had not been personally recommended, posing an obstacle for families with minimal social connections. One mother commented:

“They have told me: ‘yeah, I know places where you can leave your baby,’ but my question is- what is the person like? I don’t know them. Who else lives there?”

This report is an excerpt of significant findings from the 2022 study. For access to the full capstone thesis including the literature review, methodology, and detailed analysis of findings, click here.