Greater Minnesota is not one homogeneous region, but all parts of the region will feel the coming change from shifting demographic trends sooner and in many places more acutely than the Twin Cities metro area.

By Megan Dayton, Minnesota Demographic Center

Minnesota is in the midst of a number of large, demographic shifts that will continue to unfold over the next several years. In response, the state will be driven in an array of new directions. Public budgets and narratives, policies, practices—all will need to re-align to meet the needs of the communities that evolve. Over the next administration’s term, all of Minnesota will experience demographic changes—some dramatic—but as this brief will show, many of these trends will be amplified in Greater Minnesota.

Of course, in reality, there is no homogenous “Greater Minnesota.” Instead, Greater Minnesota is a patchwork of many different communities, regional centers and college towns, agricultural strongholds, and recreational treasures. While no two Greater Minnesota communities will experience the demographic change we expect in exactly the same way, a number of trends will exert pressure over a large swath of the state, and as with each of the trends discussed below, Greater Minnesota is poised to feel many of these shifts more acutely than the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

Along with the broad shift away from the agricultural dominance of the 1900s, Minnesota has seen its population increasingly tilt toward denser communities. Many Minnesota counties with rural characteristics are losing population share relative to more urban counties, as well as to their earlier selves. Examining population totals from 1950 to the present reveals that 36 of Minnesota’s 87 counties peaked in population in the 1950 or 1960 decennial Census count. As the shift toward greater urbanization occurs in Minnesota, state policymakers must attend to the diverse and sometimes divergent needs that exist in both urban areas and Greater Minnesota.

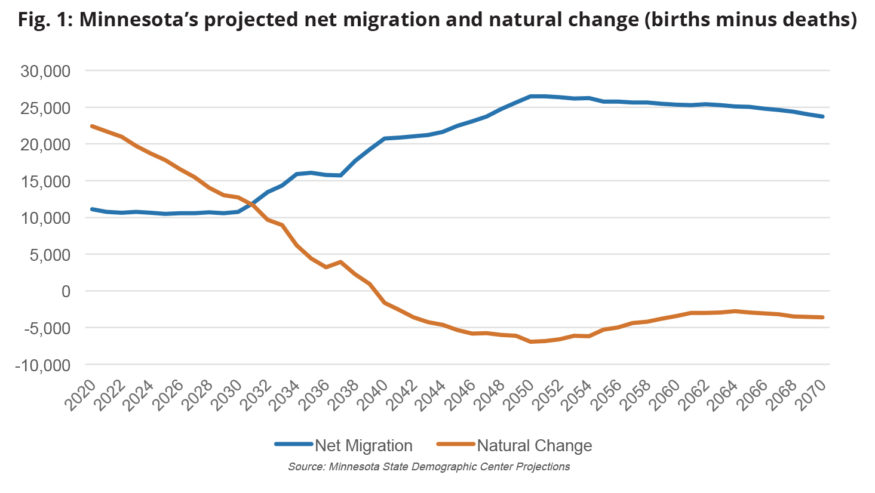

The residents of Greater Minnesota today are not the same ones as yesterday, nor tomorrow. The composition of our state is being continually transformed by demographic changes—births and deaths (the difference between the two is called “natural change”), along with migration. Projections from the Minnesota State Demographic Center show that by 2040, if our state is to experience any population growth at all, it will necessarily be from migration (Figure 1). In the coming decades, Minnesota’s population and its workforce will become increasingly older, and growth in the labor force will slow dramatically as a result. These statewide trends will of course shape any particular localities that remain above or below the overall average.

Against this shifting landscape, residents and leaders in some parts of Greater Minnesota worry about retaining and attracting working-age adults, preserving community vitality, securing a sufficient tax base to offer needed public services, and maintaining a thriving economy. In response, many communities have sought to build upon their strengths—spurring local entrepreneurship, enhancing arts and cultural offerings, and promoting their quality of life and natural amenities to attract newcomers.

Aging population

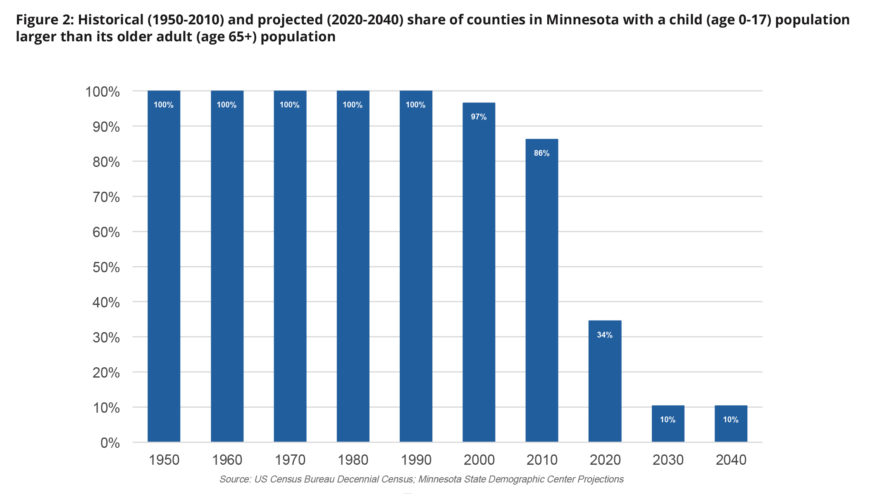

Right now, Minnesota is on the cusp of an era in which its older adult population (ages 65+) will surge to a figure that is several orders of magnitude larger than what our state experienced just half a century ago. Furthermore, the outsized influence of the Baby Boom generation (those born 1946-1964) in Minnesota means that their share of those residents who are 65 and older will also attain new highs in the coming decades. This demographic shift is not only unprecedented in Minnesota, but its implications are numerous and long-lasting. As recently as 1970, as the Boomers were coming of age, the child population in Minnesota was 3.4 times as large as the 65+ population. By 2030, nearly the entirety of Greater Minnesota will be experiencing just the opposite.

From 1950 to 1990 all 87 of Minnesota’s counties had a larger population of children (age 0-17 years) than older adults (age 65+) (see Figure 2). In 2000, three counties of Greater Minnesota (Aitkin, Lincoln, and Traverse) were the first to experience the shift of an older adult population that outnumbered the entire child population. While the size of Minnesota’s older adult population has been growing modestly since 1950, its growth is now accelerating rapidly as the Baby Boomers continue to push into this age group. The oldest Boomers turned age 65 in 2011. By 2030, the entire Baby Boom generation will be age 65+ and that is anticipated to leave only one in ten Minnesota counties—nine in total—left with a larger child population than older adult population. Seven of the nine counties are situated in the Twin Cities Metro (Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties). The remaining two are Mahnomen County and Nobles County. Nobles County, a population of over 20,000 residents, has the highest share of foreign-born residents (20% of the total population) in the state.

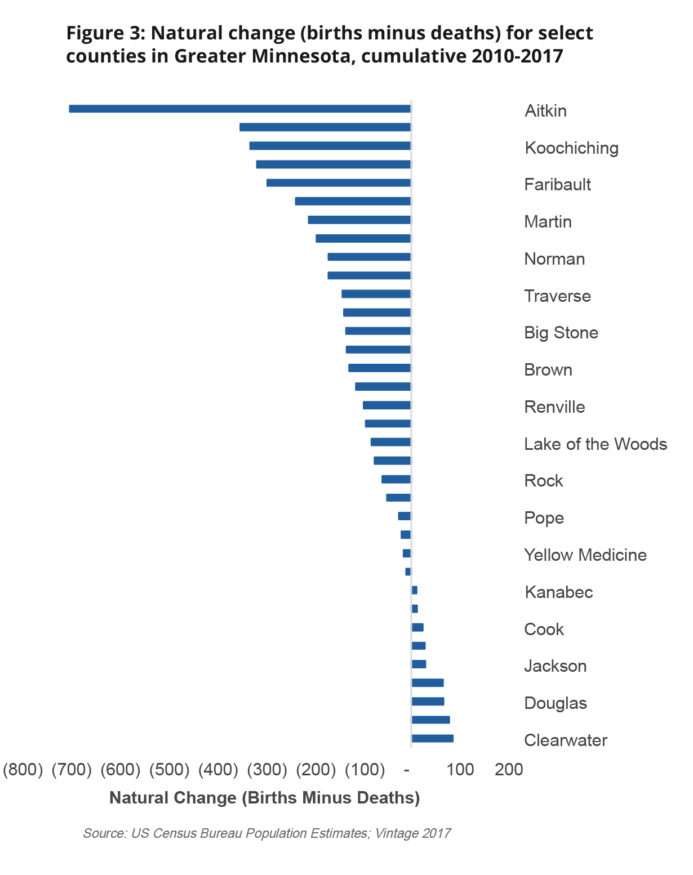

Population aging is not simply a short-term phenomenon to be weathered; rather, we are beginning a shift toward an older society that will be the reality well into Minnesota’s future. Older generations are being replaced by generations of people with different characteristics, and this change will alter our landscape in myriad ways. Between 2010 and 2017, 26 of Greater Minnesota’s counties experienced natural decrease—meaning the number of deaths in the county outnumbered the number of births (see Figure 3). Another nine were close, with fewer than 100 net additional residents due to natural change. This trend is slowly inching its way across our state. For the first time in our state’s history—by 2040—deaths are expected to outnumber births statewide, meaning that in order for population growth to occur, that growth will need to come from migration—from people currently residing beyond the borders of Minnesota and even the United States.

The strains on public and private organizations brought about by population aging will be felt disproportionately in Greater Minnesota communities. Aging will have implications for demands on public programs and services, urban/city planning, housing stock, health care, economic purchasing programs, and a range of other areas relevant to state leaders. As Baby Boomers move into retirement, an immediate implication that is already being experienced in Minnesota is the challenge among employers to properly staff and train the workforce that will replace them.

Migration

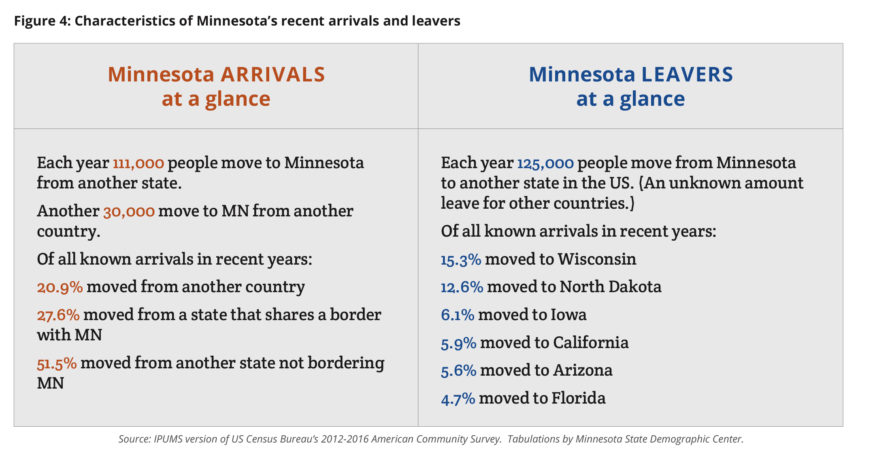

While Minnesota has experienced decades of continuous net in-migration from international arrivals, net losses from state-to-state migration have been observed since 2001 (except for 2017). Each year, about 140,000 people move to Minnesota from another state or country. Of all of our state’s newcomers in recent years, 20.9% moved from another country, 27.6% moved from one of the four states that share a border with Minnesota (North or South Dakota, Iowa, or Wisconsin), and 51.5% moved from a state that does not share a border with Minnesota. Nearly one-quarter of newcomers (23.3%) were Minnesota-born residents, returning after a spell away. Half were born in another state, while over one-quarter were born outside of the United States.

At the same time, about 125,000 people left Minnesota for another state in the US (see Figure 4). Many do not go far. The most common destination for recent leavers is Wisconsin (15.3% of all out-migrants), followed by North Dakota and Iowa (12.6% and 6.1% of all out-migrants, respectively). The next most common destinations include the sunny states of California, Arizona, and Florida (5.9%, 5.6%, and 4.7%, respectively). Recent leavers were almost equally likely to be Minnesota-born (43.1%) as they were to be born in another US state (46.2%). In addition, about 1 in 10 individuals leaving Minnesota for another state was born outside of the United States.

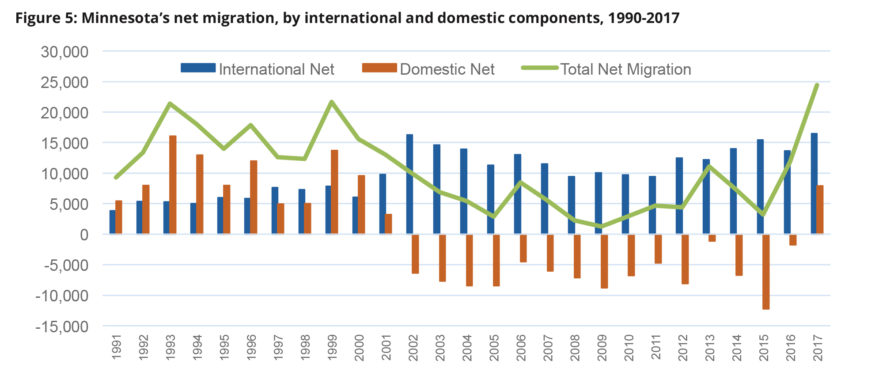

Over the past two decades, Minnesota has consistently gained more people than it has lost to other places. In the 1990s Minnesota gained an average of 15,500 people each year due to migration (see Figure 5). Since 2000, annual gains have been much slower, dipping to just 2,000 during the Great Recession—between 2007 and 2008—and the years immediately following—2009 and 2010. These gains were made entirely by international migration—occurring between Minnesota and other countries outside the U.S. For at least the last two and a half decades, Minnesota’s net international migration has been unfailingly positive. Since 2010, the number of people Minnesota gained, on net, from other countries has averaged nearly 13,000 annually. The growth in international migration has more than compensated for the recent losses Minnesota has experienced to other states. In 2017, for the first time since 2001, Minnesota experienced net positive levels of both international and domestic migration. While 2017 could signal a turning point for Minnesota, it will take a few more years before we will know whether this is the beginning of a new era of greater domestic migration to Minnesota or just a temporary anomaly.

States with high population growth are sustained by migration—international and domestic—and Minnesota has been a long sought-after destination for migrants of many backgrounds. As the numerous members of Minnesota’s Baby Boom generation move into the later seasons of their lives, death totals will rise. As previously discussed, within the next three decades, the number of births in Minnesota will be eclipsed by the number of deaths for the first time in our state’s history (see Figure 1). The prospect of a declining population base would have several natural consequences—reduced consumer spending and tax revenues, with the attendant challenges to maintaining economic growth and fulfilling public priorities. Given this confluence of demographic and economic factors, migration will be increasingly important to Minnesota’s future.

Workforce changes

Over the past few years, Minnesota has ushered in a new era of slow labor force growth. This slow growth is not unexpected. The demographic trends at the root of this change are large, slow-moving, and relatively straightforward to predict. Neither is the slowdown limited to a single area of the state. In fact, parts of Greater Minnesota have already begun to feel the pinch and indeed are poised to experience mounting pressures in the coming years. From the Iron Range to Central Lakes Region to the farms and agricultural businesses of southern Minnesota, employers across a range of industries are now reporting difficulties finding workers—a situation brought on, in part, by demographic trends that have been decades in the making. At the same time that the demographic makeup of Minnesota is putting the brakes on labor force growth, strong economic growth statewide has sustained a growing need for workers and increased the pressure many employers are experiencing as they search for the workers they need to sustain and grow their businesses.

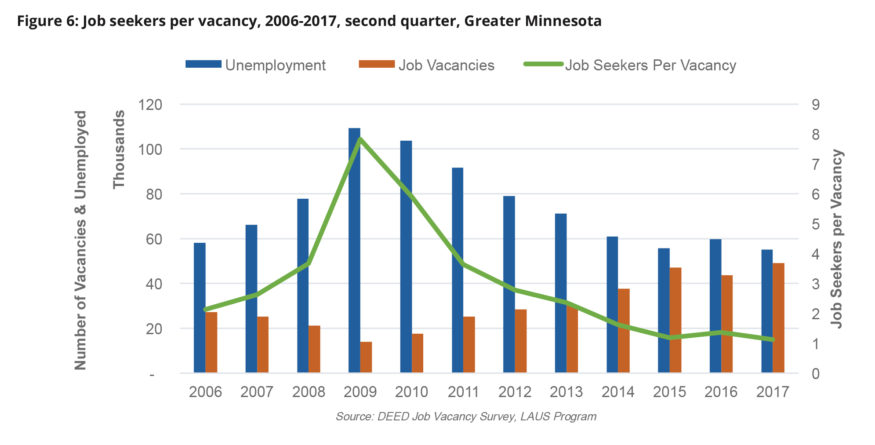

In 2009, Minnesota experienced unprecedentedly high numbers of unemployed persons and low levels of job vacancies. During that year, there were 7.8 job seekers per vacancy (see Figure 6). Since 2009, job vacancies in Greater Minnesota have increased and the number of job seekers has plummeted to a record low of 1.1 per vacancy.

The Minnesota State Demographic Center has projected labor force numbers for each of Minnesota’s 87 counties. As well as projecting the total workforce, also available is a prediction for a total of ten age cohorts in each of the 87 counties. The labor force participation rate declines rapidly in older ages—from a peak average of nearly 90% participation for all Minnesotans aged 25 to 29, down to just 6% for those aged 75 years and over (American Community Survey 2012-2016). Because of these lower rates of participation, the massive number of aging Minnesotans simply will not be able to buoy up the labor force like they once did. While replacement generations are anticipated to have identical rates of participation, because these groups are considerably smaller in number, the labor force growth will halt. This dataset fetters the health and vitality of our workforce with the most foundational aspect of an economy—the very availability of workers.

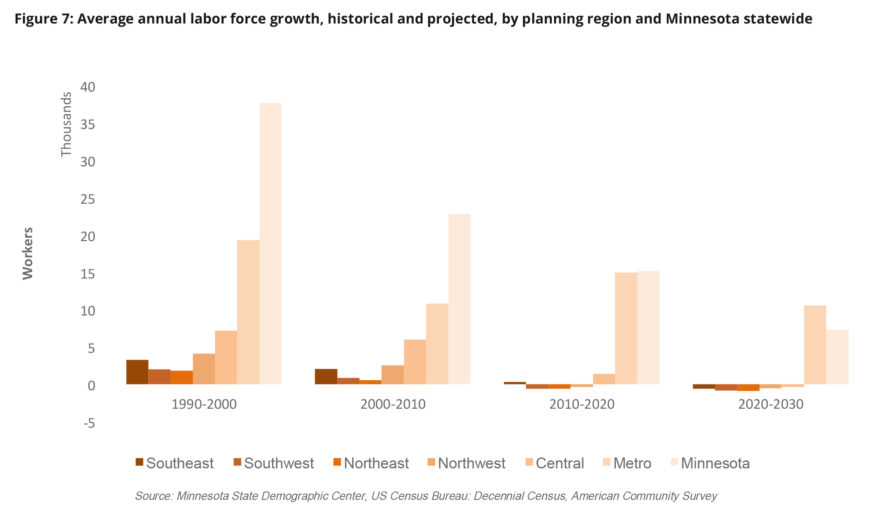

Every region of Greater Minnesota is projected to have a declining labor force between 2020 and 2030 (see Figure 7). Over 80% of our counties will be losing workers, meaning only 10 counties in Greater Minnesota are expected to maintain labor force growth. Overall, the workforce of Greater Minnesota is expected to decline through the next decade by a total of around 32,500 workers.

Some areas of Greater Minnesota have done well in recent history to attract workers. Many other areas have experienced ongoing losses of their youngest workers, and these losses are reducing the size of the workforce. Added focus on stemming and reversing domestic losses is required. Maintaining or increasing international gains while invigorating efforts to attract and retain homegrown workers of the current resident population is going to become absolutely essential for Greater Minnesota’s labor force.

As supply of jobs surpasses available workers, businesses may be compelled to increase wages to find suitable candidates. Businesses concerned about inflation and uncertain about their future may wish to avoid building high wages into their permanent cost structure. Instead employers may try to make one-time bonus payments and offer other non-monetary benefits to entice workers. A few examples are recognition and reward, flexible work environments, job laddering opportunities, rewards for qualified referrals, and recruiting remote workers.

For various reasons, not every working-age adult is currently working or seeking work. A tight labor market may lead to workers finishing school more quickly, or even delaying a degree entirely, while retired Minnesotans might be lured back to work. If businesses were to loosen some workplace requirements and ease minimum job qualifications, we could see an increase of workers with traditional barriers to employment entering the labor force. If a skills gap remains between workers re-entering the labor market and the job vacancies, training and educational opportunities—such as certificate programs or on-the-job training—will be key to ensuring workers are ready and suitable for open positions. It will also be critical that workers have the housing, transportation, and childcare options needed.

Many of the consequences of the tight labor market benefit workers, such as higher wages and more employment options. However, they can also lead businesses to invest in automation or relocate to an area with more available labor and higher population growth as costs rise. Ultimately, these trends are mitigated by other forces. Inflation-adjusted wages for the typical worker have been relatively stagnant across the last few decades due to union decline, slow productivity growth, low business dynamism, and the decline of inflation-adjusted minimum wage. Businesses may resist inflationary wage pressures if new domestic or international workers are drawn into the labor force who have less experience than retiring Baby Boomers. Employers could also find mechanisms other than wage increases to recruit and retain workers if businesses find ways to increase efficiency, economic growth is anemic, or workers are not employment-ready. While each industry will have different challenges and strategies in hiring and maintaining their labor force, workforce training, re-skilling, and diversity initiatives will aide in meeting the changing realities of labor force demographics and maximize the human potential currently available in the state.

Conclusions

Minnesota is truly on the cusp of a new era. The population is aging quickly and for many communities any growth at all will have to come from the individuals who are currently residing and working beyond our state and national borders. The demographic trends, set in motion decades ago, are now shaping the availability of workers and ultimately the health and vitality of Greater Minnesota communities. As the demographic changes highlighted in this brief play out, Greater Minnesota will have a choice to make: communities will either need to recruit new residents—from another part of the state, a different state, or abroad—or realign expectations, budgets, and institutions around a slow- to no-growth future. Minnesota leaders are encouraged to consider these emerging demographic environments and their social and economic consequences in order to shape proactive responses to the challenges and opportunities to come.

Megan Dayton is the Minnesota State Demographic Center’s Senior Projections Demographer and is responsible for preparing the state’s annual population projections.