Minnesotans may wonder why they should care about what happens to one lake on the southeast border of Minnesota, but Lake Pepin’s unique structure and position on the Mississippi River makes it a canary in the coal mine for water and environmental health across the state.

By Rylee Main, Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance

Communities around Lake Pepin in southeastern Minnesota have been anxiously awaiting a statewide plan that will reduce the calamitous impacts of accelerated siltation at the head of the lake. The enforcement of Minnesota’s only regulatory solution for non-point source pollution – a strip of vegetation commonly known as a buffer – is a victory for those who care about and depend on Lake Pepin. Yet the question remains: Is it enough?

In the land of 10,000 lakes, one might wonder how any unique lake could represent water quality impairments across the diverse landscape of Minnesota. Then again, Lake Pepin is not your typical lake. At the widest stretch of the entire Mississippi River, Lake Pepin is uniquely positioned to act like a sediment trap, with more than half the land in Minnesota draining its waters into this riverine lake.

Moreover, one might wonder why farmers across Minnesota should care about a body of water up to a few hundred miles away. “Aside from an altruistic recognition of its value, they should care because their future will be linked to the lake’s future,” wrote Mike McKay, former chair of Minnesota’s Clean Water Council and Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance’s first Executive Director. He went on to say:

“As the science surrounding non-point source pollution grows, there will be inevitable pressure on farmers to employ best practices. While the future of Pepin is important on its own merits, its health is also an indicator of larger concerns. After all, the same farm runoff that imperils Pepin contributes to the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Those farmers who choose to take advantage of conservation programs that exist today will have a leg up on their colleagues who don’t. In the years to come, it’s a fair bet that some of those voluntary programs will turn to mandates. Why? When public waters are degraded, after a while people stop asking for change and start demanding it.”

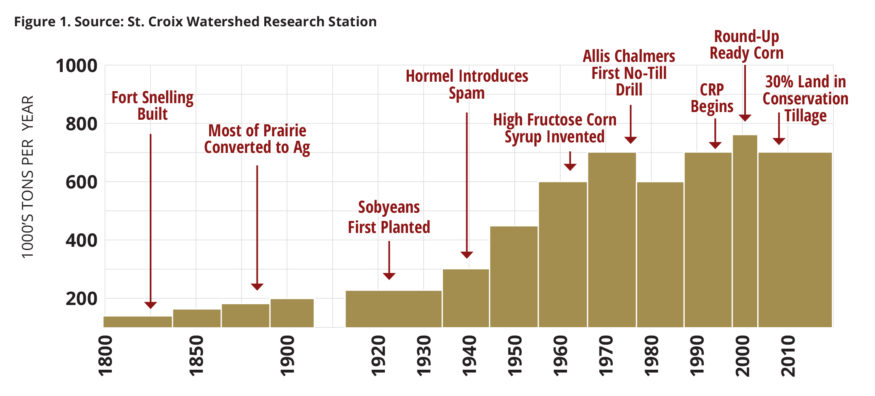

Scientists at the St. Croix Watershed Research Station – part of the Science Museum of Minnesota – believe that Lake Pepin is not only unique in Minnesota, but also unique across the world in its ability to tell the story of human development through sediment cores taken from the bed of the river. These cores are made up of soil that has washed away from land across Minnesota and made its way through ditches, rivers, and streams to Lake Pepin. Once it reaches the lake, the flow slows and sediment drops to the riverbed. The research station has studied these layers of mud extensively to see how the upper Mississippi River watershed has changed in the past two centuries.

The most significant finding from this research shows that major changes in farming technology, policy, and market forces have led to sediment accumulating more quickly. In fact, sediment accumulation at the head of Lake Pepin has increased nearly ten-fold since the mid-1800s, when most of the prairie in Minnesota was converted to agricultural land. Today, approximately one million metric tons of sediment accumulates at the head of Lake Pepin each year. To put this in perspective, that amount of sediment is equivalent to a full city block raised to the height of the Foshay Tower in downtown Minneapolis.

The water quality impairments in Lake Pepin are nearly a direct result of the impairments in the Minnesota River Basin – a primarily agricultural area covering more than 30 counties across the lower third of the state. In any given year, up to 90% of the total sediment load delivered to Lake Pepin originates in the Minnesota River and its tributaries.

Sediment flowing from the Minnesota River to Lake Pepin is not just a problem for the communities experiencing social and economic hardship adjacent the lake, but it also has major impacts upstream where the soil erodes.

Don and Becky Waskosky own a home on the Le Sueur River (a tributary of the Minnesota River) and shared their story with the Minnesota Humanities Center as part of the We Are Water MN initiative. “In 2010, a train of thunderstorms went across the southern part of the [Le Sueur] watershed and we lost 20-25 feet in our back yard within a day and a half,” Don recalled. He went on to describe the experience:

“It went down in clumps. You could hear it and you could smell it. You could smell the dirt in the air. And the river had a growl to it, which was a little frightening when you sit there and watch your land disappear. We didn’t know what we would wake up to in the morning.”

As the edge of the bluff moves closer to their home each year, Don and Becky realized they had to take action, so they teamed up with the Le Sueur River Watershed Network. “We’re working with farmers to set up drainage ponds, so that water can be metered to the river as opposed to it going directly from tile, into ditch, into river,” explained Don.

Don and Becky are not alone in their efforts. Among the many organizations working to improve water quality, soil health, and productivity of farm land, the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance (LPLA) has also heeded the call. In 2010, LPLA collaborated with organizations across the Minnesota River Basin, bringing together agricultural producers, local governments and residents up and down the river to create a shared understanding about water quality issues affecting the Minnesota River and Lake Pepin.

Despite the vast amount of water quality research and data collected over the past ten years, the Minnesota River has only seen a 1% reduction in sediment loading. What the data and scientific recommendations fail to account for is the human element of land use change. Meeting water quality goals under a mostly voluntary plan means that the mindsets of individuals matter.

Over the years, many individual minds have been changed, and while not exactly quantifiable, anecdotally we know that relationships matter. Sharing stories of businesses along Lake Pepin closing because the water is now too shallow for boaters to access adjacent river towns is powerful. Even more powerful is taking the time to listen to the constraints faced by upstream landowners, and then working together to find solutions.

Even with these relationship-building efforts and thousands of successful projects implemented upstream, Lake Pepin remains vulnerable to ecological collapse. The summer of 2017 shed light on just how prolific the issue of siltation has become. Boat groundings at the head of the lake were at an all-time high, with more than 30 boats unable to free themselves without the help of expensive towing equipment. One local resident offered his concerns, “This part of the lake hardly gets used because people can’t get their boats through unless the water is high. So your business can’t make it… Bay City has become kind of second rate, but it hasn’t always been like that. Only since we’ve been increasingly cut off.”

Not to mention how the cloudy water that results from this siltation has decreased the amount of aquatic vegetation present in the area, threatening Lake Pepin’s fish and wildlife populations. Once abundant tundra swans that fed on plentiful arrowhead are now dwindling in numbers, and many backwaters are too shallow for fish to over-winter. Without remediation, Lake Pepin will drastically change from a 26,000-acre lake, with depths of up to 60 feet, to a marshy swamp with only a navigational ditch used for commercial traffic. Local residents may not be wondering what they will wake up to in the morning, like Don and Becky, but they are wondering what will be left behind for their kids and grandkids.

In 2015, Governor Mark Dayton set in motion legislation aimed at improving water quality through strips of vegetation known as buffers, which are now required along all public waterways and ditches. While the implementation of buffer strips represents an important step toward improving water quality, passing of this legislation did not happen without some discontent.

Primarily, many farmers were concerned about the lack of flexibility within the buffer legislation to account for diverse landscapes. LPLA met with farmers in Goodhue County to learn more about their concerns.

“Buffers are absolutely needed, but farmers need flexibility too… upland practices like grassed waterways, no-till, and cover crops (for example) can solve more than half the problem, but buffers are only required along the banks of waterways under the current law.”

This particular farmer is referring to the need to slow down the flow of water across the land before it reaches a waterway. “Water running into ditches, streams, and rivers picks up speed as it flows downhill… By the time it reaches my land, it has already captured all of the runoff from upstream landowners’ properties,” he explained.

While buffers help to stabilize stream banks and have some ability to filter nutrients and loose soil, they tend to be less effective in areas with steep slopes or in places where tile drainage flushes water directly into a river system, bypassing the filtration that buffers can provide. Hence, Don and Becky’s efforts to set up drainage ponds that meter the water.

In one of the most erosive watersheds in the state, a group of researchers involved in the Collaborative for Sediment Source Reduction led a five-year effort to evaluate strategies for sediment reduction in the Le Sueur River Watershed. Among their findings, the group concluded that “a solution to the sediment loading problem must address the largest source of sediment: the steep bluffs along the incised portions of the watershed… Bluffs contribute about 60% of the sediment delivered from the watershed to the Minnesota River.” The findings went on to say that sediment loss from bluffs can be reduced by reducing the frequency and magnitude of flood flows, and actions taken to reduce river floods offer a potentially long-term solution that gets at the cause of the problem.

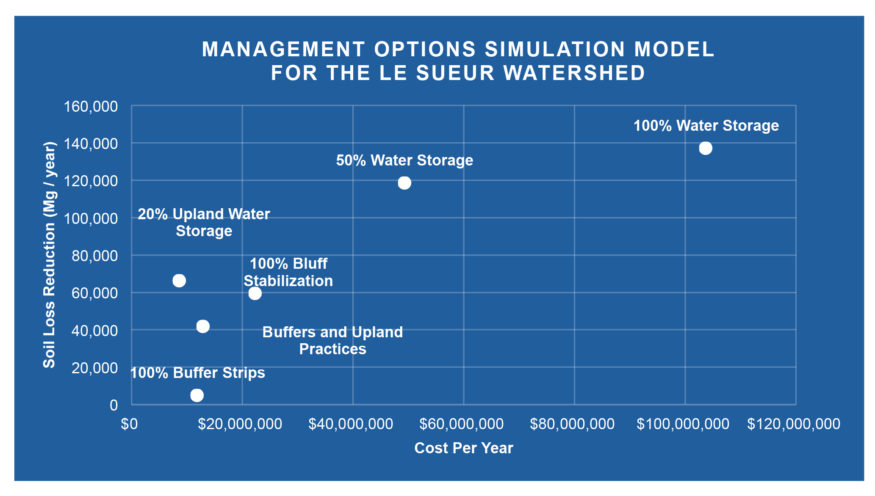

A model developed by the Collaborative allows users to choose management options and compare the reduction in sediment and cost per year. The model takes into consideration a wide variety of factors, including crop prices, land prices, installation costs, maintenance costs, and the availability of land within the watershed to actually implement any of these options. The chart below displays a selection of management options for the particularly erosive Le Sueur River watershed.

Storing water has the greatest potential to reduce soil loss; but taking all suitable land out of production is cost-prohibitive and politically infeasible. Even 20% water storage is not supported by local Soil and Water Conservation District staff as a realistic option for landowners. More practically, if we compare 100% buffer strips (which is the current law) and buffer strips with upland practices (e.g. water storage, grassed waterways, no-till, and cover crops), there is a significant increase in the amount of sediment reduced, with only a minor increase in cost. The point being that buffers are more effective when implemented in conjunction with other practices, and the cost benefit ratio shifts from $2,450 per 1 Mg of sediment reduction with buffers alone to $309 per 1 Mg of sediment reduction when buffers are combined with upland “best management” practices.

All of these numbers are meaningless, however, unless we have clear goals to improve water quality and a willingness from landowners to implement changes. The former, we have, but the latter – being heavily influenced by market forces—still needs work.

A 50-60% reduction in sediment loading from the Minnesota River is needed to meet the site-specific water quality standards set for Lake Pepin. On average, 65% of the suspended sediment leaving the Minnesota River arises from the Le Sueur and Blue Earth watersheds. Local watershed planning efforts in the Le Sueur River watershed call for a reduction in suspended solids of about 150,000 Mg/year (approximately a 65% reduction). Referencing the high costs associated with this level of reduction, as displayed in the model above, one can begin to see why relatively little progress has been made.

Going beyond buffers to support the resiliency of communities upstream and downstream will require innovation and flexibility. As government and non-government organizations alike work towards technical and market-based strategies to improve water quality, Minnesota can provide collaborative leadership to protect Lake Pepin and prevent further loss of farmland to unnecessary erosion. Prioritizing upland practices in conjunction with the current law, emphasizing and investing in water storage, and working to reduce barriers that impact the willingness of landowners to risk changing their production system must all be a part of the strategy.

Rylee Main is executive director of the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance and serves on the Clean Water Council.