Across Minnesota, the “opioid crisis” is so much more than just opioids

June 2018

By Marnie Werner, VP Research & Operations

For the executive summary, click here. For a printable version, click here.

If there were any doubt that opioids are the major health emergency of our time, two facts can put that doubt to rest:

- Of the approximately 64,000 overdose deaths in the United States in 2016, opioids were involved in about two thirds of them,[1] and

- Opioid abuse has been deemed single-handedly responsible for lowering the overall life expectancy in the U.S. for the past two years.[2]

Nationally, the death rate from opioid and heroin use per 100,000 has gone from 6.1 in 1999 to 16.3 in 2015.[3] The situation has become so dangerous, in fact, that first responders carry the opioid antidote naloxone with them, not just to revive possible opioid overdose victims but to use it on themselves in case they come in contact with any of the new, incredibly dangerous synthetic opioids being sold and used out there.[4]

Minnesota is not immune to the opioid epidemic, as evidenced by successive news stories and ongoing discussions on what to do about it.

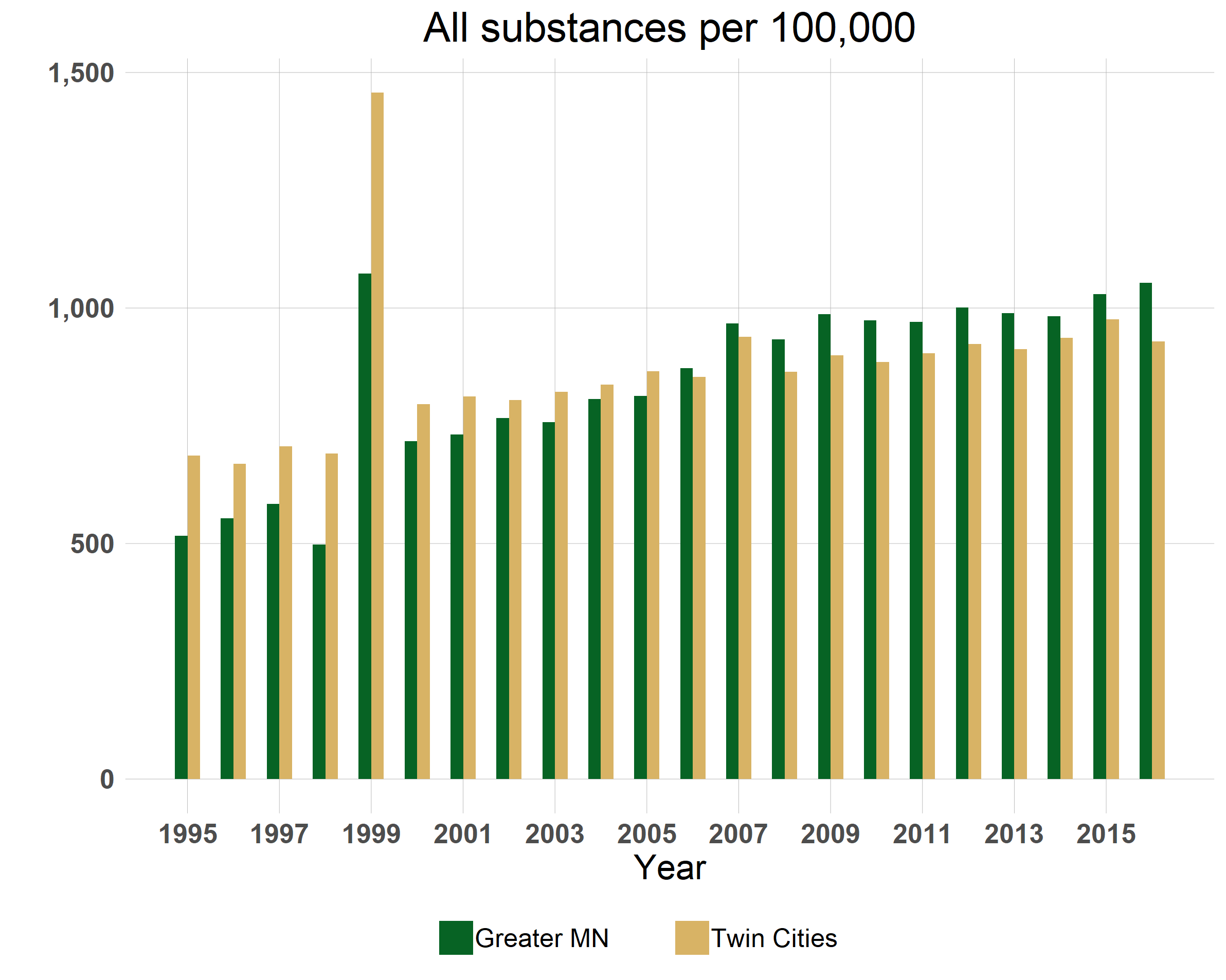

The data on drug overdoses, emergency room visits and admissions to treatment tell a different story, however: one that is more endemic, more varied and definitely more complicated than opioids and farther reaching than the Twin Cities.

What the statistics indicate is that our state isn’t facing an opioid crisis as much as it is facing an addiction crisis, and the drug of choice—for now—is meth. Since 2009, treatment admissions for meth in Greater Minnesota have skyrocketed compared to opioids, including heroin. And while overdose deaths due to opioid use are at alarming levels, deaths due to meth use are on the rise, too.

While counties struggle to keep up with services and control their budgets, law enforcement is seizing record amounts of illegal substances, and the cost is mounting at hospitals around the state. But there is hope. Philosophies and understandings around addiction and its underlying mental and emotional issues are changing, while the increased demand for treatment staff is being met with growing interest from career-seeking students. And communities themselves are working out solutions to their unique problems.

Drug addiction rarely operates in isolation, and it is hardly victimless. It affects generations of families, communities large and small, local government and the state, from the most distanced taxpayer to the smallest newborn baby.

The immediate threat

The opioid crisis dominates headlines for good reason. The death toll is unnerving and the backstory approaches the realm of “you can’t make this stuff up”: an unsuspecting public that would never think of touching illegal substances develops frightening addictions to medication given to them for legitimate pain by doctors who may or may not be aware of the addictive properties of the drugs that have been created and promoted by pharmaceutical companies often portrayed as money hungry.

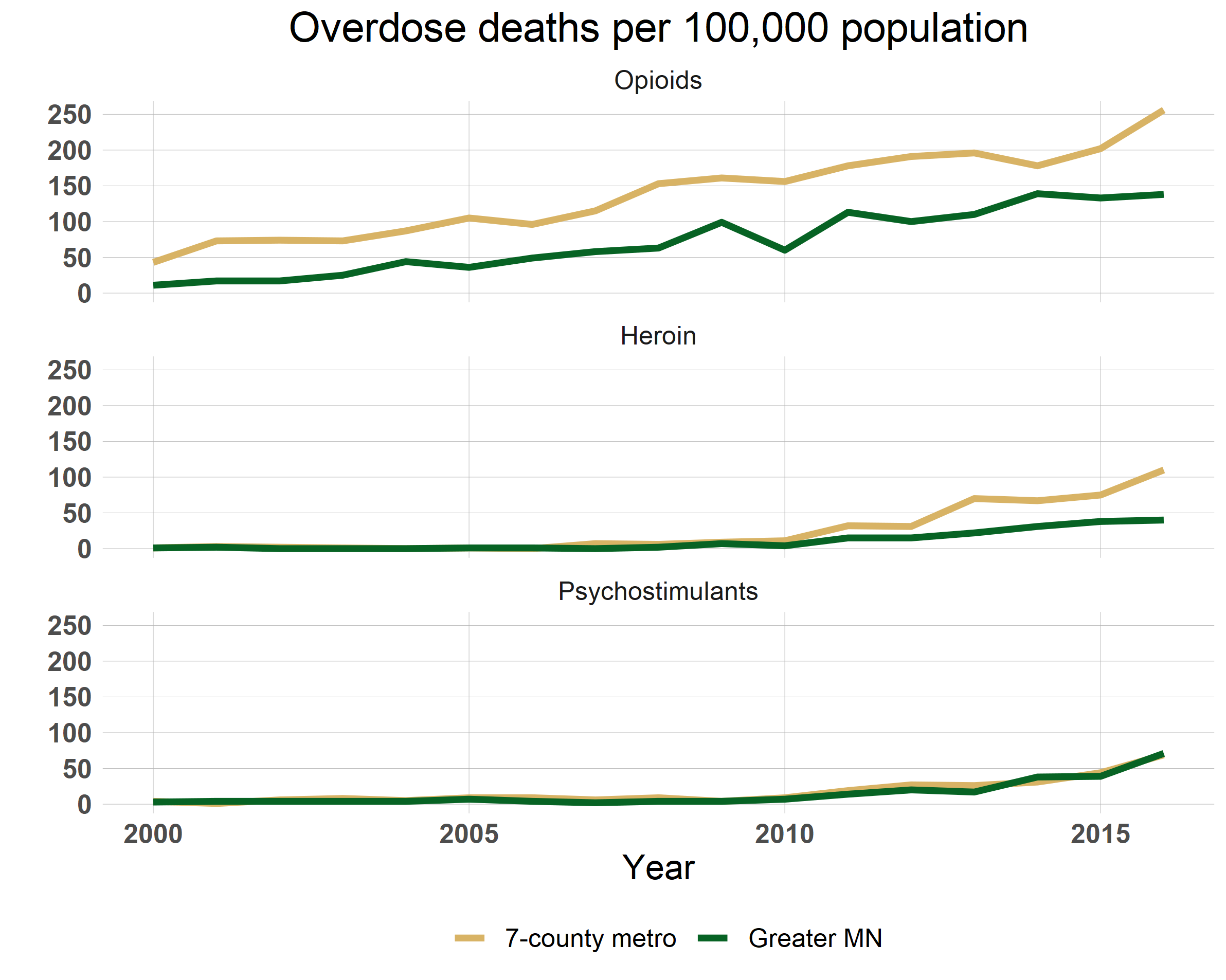

In 2015, Minnesota ranked near the bottom (45th out of 50) in overdose deaths compared to other states. In 2016, though, Minnesota stood out as one of several states that had a statistically significant increase in drug overdose deaths (17.9%) between 2015 and 2016.[5] According to data from the Minnesota Department of Health, between 2000 and 2016, deaths from opioids (which in this case includes prescription opioids but not heroin), increased 631% across the state. Figure 1 compares the death tolls per 100,000 residents in the seven-county Twin Cities area and Greater Minnesota for opioids, heroin and psychostimulants, which includes meth. The death toll in the Twin Cities increased by almost 495%, while in the rest of Minnesota it increased 1,155%. Overdose deaths for heroin and psychostimulants, which includes meth, are on the rise as well.

And in Minnesota, the disparity in overdose deaths based on race is among the worst in the nation. According to the Minnesota Department of Health, while the overdose mortality rate in the white population went from 10.1 per 100,000 white residents to 11.7 between 2015 and 2016, the mortality rate among Native Americans went from 47.3 to 64.6 per 100,000 Native American residents, while the rate among African Americans went from 20.8 to 24.0 per 100,000 residents.[6]

Policy makers have been cracking down on access to the supply of prescription opioids. As they do so, users have been turning to illegal alternatives, including heroin and the extremely powerful synthetic opioids fentanyl and carfentanil. Particularly deadly is carfentanil. One hundred times more potent than fentanyl and 10,000 times more potent than morphine, carfentanil was invented to be used as a tranquilizer for very large animals, such as elephants.[7] As addicted users seek out a more powerful hit, producers and dealers cut in drugs like fentanyl and carfentanil for an added kick. Because of the minuscule doses involved, however, dealers can’t be sure how much they’re putting in, and users have no way of knowing how much they’re getting. A tiny dose—even skin contact—can be fatal.

The bigger picture

But while society has been mobilizing against opioids over the last couple years, in rural areas of Minnesota, especially in northern Minnesota, methamphetamines have come surging back.

Meth was a growing cottage industry in the early 2000s, mostly rural and mostly small time, with home brewers cooking up the drug in basements and abandoned farm houses across the state. After legislation was passed to put its key ingredient, pseudoephedrine, behind the pharmacy counter, methamphetamine production—and use—tumbled.

In the last several years, however, meth has returned. Mass-produced in large labs in Mexico and smuggled into the U.S., this new product is much purer, up to 90%, says a 2017 MinnPost article, and the mass production has made it much cheaper.[8] A pound of methamphetamine that cost between $21,000 and $22,000 wholesale a few years ago now sells for around $5,000, that same article stated.

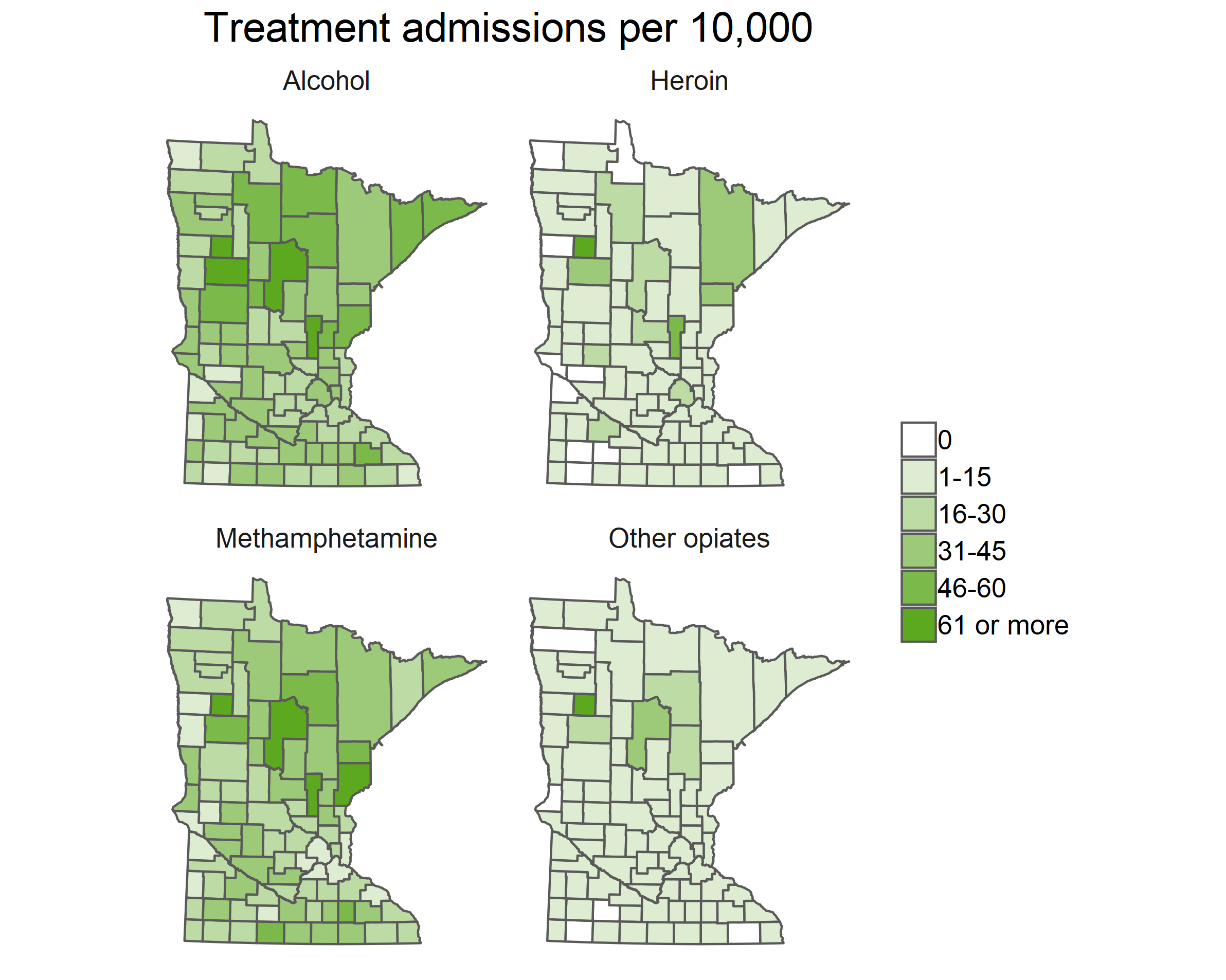

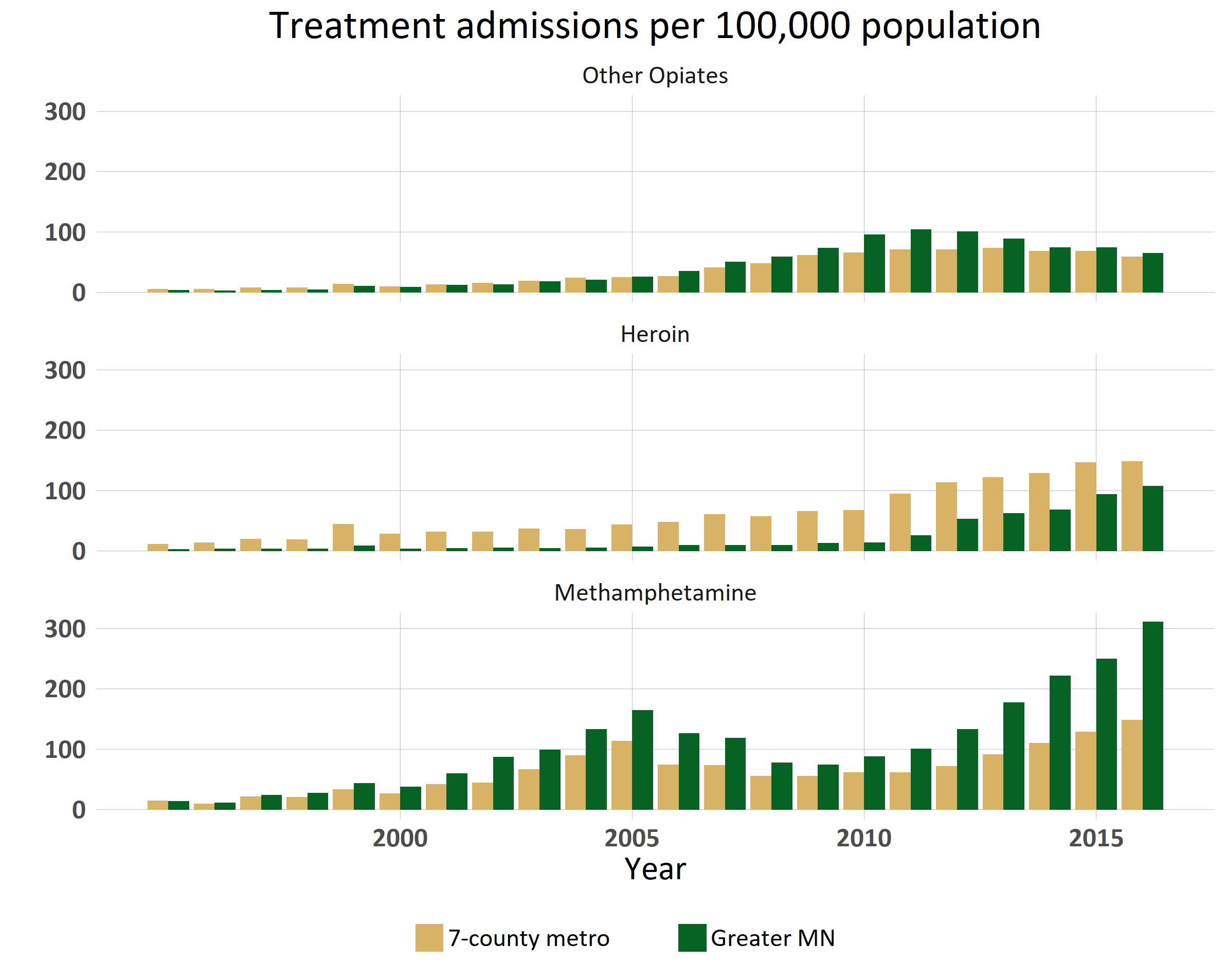

Meth was and still is a bigger problem in Greater Minnesota than in the Twin Cities. Besides tracking treatment admissions approved by social services, the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) also records the primary substance being used at the time of admission. (Note: the primary substance may not be the only substance in use at time of admission.) Figure 3 compares the trajectory over the past ten years of admissions for “other opiates” (including prescription opioids), heroin and meth for the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota, adjusted to show admissions per 100,000 population. These treatment admissions statistics do not include people who covered treatment with private insurance.

While admissions data does not represent the entire universe of everyone using these drugs, it is an indication of what may lie below the waterline, says Glenn Anderson, a board member of the Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment in Duluth and the recently retired director of the Northern Pines Mental Health Center in Brainerd, which also offers a chemical health center.

The national focus on opioids is understandable: meth doesn’t kill people like opioids can. The lethality just isn’t there, says Anderson.

But after bottoming out in 2009, admissions to treatment for meth have been on a climb almost straight up in Greater Minnesota, and the numbers are following suit in the Twin Cities. In 2016, 7,664 people in Greater Minnesota sought out treatment for meth addiction, a 25% increase over the year before (6,164) and almost twice as many as in the Twin Cities (4,386).

But after bottoming out in 2009, admissions to treatment for meth have been on a climb almost straight up in Greater Minnesota, and the numbers are following suit in the Twin Cities. In 2016, 7,664 people in Greater Minnesota sought out treatment for meth addiction, a 25% increase over the year before (6,164) and almost twice as many as in the Twin Cities (4,386).

In terms of numbers, alcohol has long been the most-abused substance, cited the most often when entering treatment, followed by marijuana. Meth has seen such a resurgence, however, that in 2016 around one third of Minnesota counties reported having as many or more people being admitted to treatment for meth as alcohol.

“This is a major sea change,” says Tami Lueck, programs manager for Crow Wing County Community Services.

County budgets: The buck stops here.

In rural areas, this sea change takes its toll especially on counties, both financially and socially. Talking to a few county officials helps explain the ripple effect the opioid/meth epidemic is having.

“For the majority of people involved in child protection services, probation, and our court system, chemical dependency appears to be the main contributing factor,” says Cass County Administrator Joshua Stevenson.

| Cass County | Alcohol | Marijuana | Meth | Cocaine/ Crack |

Heroin | Other opiates | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 170 | 64 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

2 |

| 2016 | 176 | 127 | 188 | 2 | 45 | 103 | 8 |

Table 1: Rule 25 admissions to chemical dependency treatment via Cass County Social Services in 1996 and 2016. (Minn. Department of Human Services)

As Table 1 shows, in 1996, 249 residents of Cass County were admitted to treatment for chemical dependency. Twenty years later, 473 people were admitted to treatment, according to Minnesota Department of Human Services data. Note that alcohol barely moved.

Counties are the gatekeepers for access to social services for most Minnesotans. The role of county social service staff is ideally to be case managers for those in treatment, tracking individuals through the system, making sure they are making it to treatment, getting their housing supports, and accessing other services they may need, like general health care and mental health services. The number of people needing case management now, though, is threatening to overwhelm many counties, especially up north, and bust their budgets.

In the spring of 2018, Beltrami County had two case managers overseeing around 300 cases between the two of them, says Jeff Lind, Beltrami County Social Services Division Director. “They can’t manage cases,” he said. “They can only make sure providers get paid.” The county is in the process now of hiring two additional staff to their chemical dependency unit.

The impact of substance abuse goes beyond the individual with the addiction. Substance abuse is in fact the most common reason for out-of-home placements for children, according to a 2017 MN DHS report.[9] It can create surprisingly complex situations, and complexity adds cost for counties and trauma and upheaval for the individuals involved, especially children.

Stevenson provides a hypothetical but not unusual situation that illustrates not just substance abuse itself but the host of issues that can accompany it, like domestic abuse and mental illness:

Stevenson provides a hypothetical but not unusual situation that illustrates not just substance abuse itself but the host of issues that can accompany it, like domestic abuse and mental illness:

A mother with substance abuse problems has four children by four different fathers. If the mother is arrested or committed for treatment and the children are taken away, the court becomes involved, in which case the mother has an attorney, each of the four children must be represented by an attorney, and each of the four fathers has an attorney. Since they are in “the system,” the mother has her own social worker, the four kids have social workers, and since the fathers are now involved and in the system, they are each assigned a social worker as well. And they’re all on public assistance.

Because of situations like this one, the Cass County clerk of court’s budget went up 72% in a single year, from 2017 to 2018.

“The cost of processing all this has gone through the roof,” says Stevenson. “The current system is not working.”

Rising addiction rates pose a serious threat to children

Perhaps the most serious implications for the future are what the drug epidemic can do to children, even before they are born.

More than 1,300 newborns born in 2016 were exposed to drugs and alcohol in utero, up from 624 in 2012, according to the Minnesota Department of Human Service’s most recent child maltreatment report: “Newborns exposed to drugs are at a high risk of long-term behavioral and developmental problems and are among the hardest to place in permanent homes, researchers have found.”[10]

Neonatal abstinence syndrome is the primary concern. NAS, where the child is born effectively addicted to the drug, causes newborns to experience withdrawal symptoms that range from tremors and difficulties feeding to seizures and respiratory distress. (Recall the so-called “crack babies” of the 1990s.) Neonatal abstinence syndrome can affect anywhere from 45% to 94% of infants exposed to opioids before birth, a National Institutes of Health report states.[11] The outcome is children dealing with lifelong social, emotional, behavioral and physical problems, increased health care costs and low achievement.[12]

In Minnesota, the instances of NAS have been going up at an alarming rate (Table 2), although the Minnesota Department of Health cautions that the cases may also be going up as medical providers become better at recognizing and diagnosing NAS.

| Frequency of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome | NAS rate per 10,000 | |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 239 | 35.4 |

| 2015 | 765 | 109.6 |

Table 2: Diagnoses of NAS have been rising steadily from 2012 to 2015.

(Source: MN Department of Health, MDH Opioid Dashboard)

The effect of methamphetamine on an unborn child doesn’t appear to be as well studied or at least as widely publicized, but one publication from the North Dakota Department of Health states that children born to mothers using meth during pregnancy can suffer from NAS-like problems, plus issues including birth defects to the brain, heart, spinal cord, kidneys and limbs, premature birth, stroke and emotional problems.[13]

Substance use during pregnancy is only one part of the complicated web of risks drugs pose to children. A study of studies by the University of Arkansas on risks to children from parental substance abuse found that the adverse home environment a child may live in adds to and interacts with the effects of prenatal exposure to drugs and alcohol, increasing a child’s risk of developmental problems, and these risks build up over time. “[I]t is the build-up of risk factors that poses the greatest threat to the child,” the report’s authors state. While these risks can also come from the father and other caretakers, mothers have the greatest impact on their child’s future.[14]

Arrests and seizures

Greater Minnesota’s jails are also on the front line of the drug epidemic. Stevenson, the Cass County administrator, checks the in-custody list every morning, “and it’s the same individuals and same families every day,” he says. “They get the same treatment, but nothing changes.”

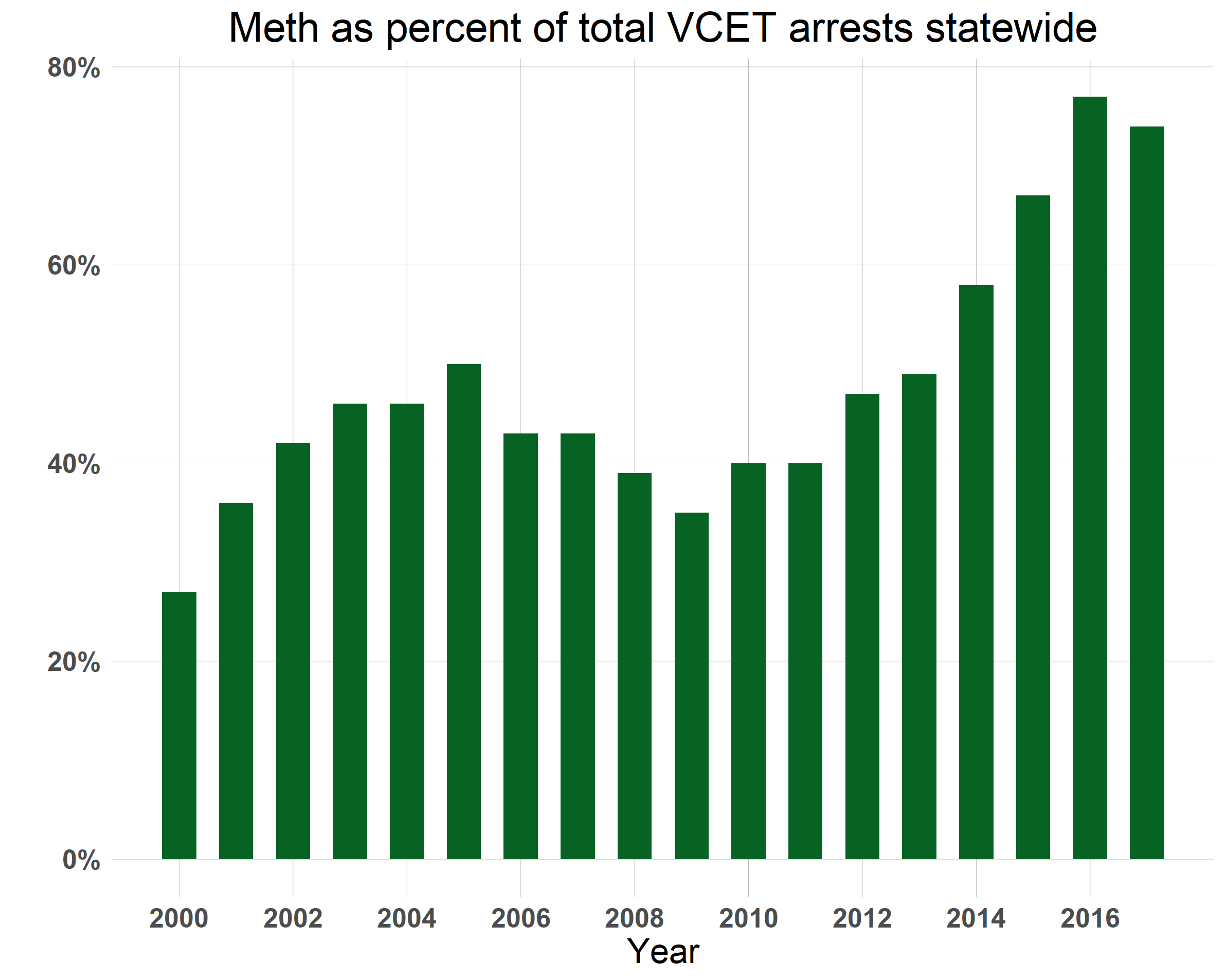

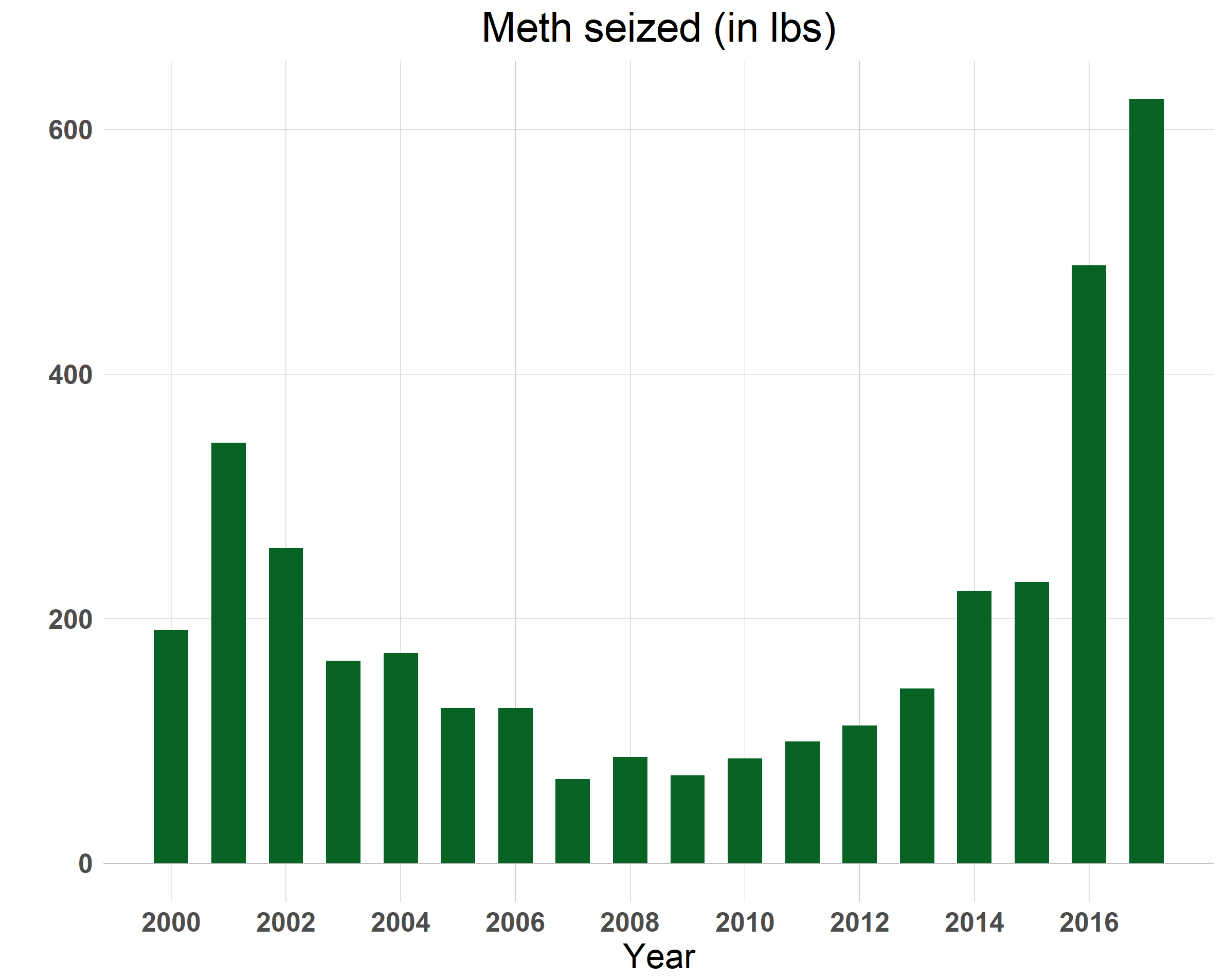

The state is seeing a spike in arrests for meth. In 2001, 27% of drug arrests were for meth; in 2017 it was 74%, according to Minnesota Department of Public Safety data—2,125 arrests involved meth compared to 750 arrests that didn’t (Figure 5).

The largest drug seizures (and largest increases in drug seizures) have been in marijuana, going from 390 pounds seized by the State Patrol in 2016 to 2,642 pounds in 2017. The amount of meth seized by the State Patrol in 2017 was also up more than double that of 2016, 160 pounds compared to 66 pounds the previous year.[15] According to DPS data, the state’s multi-county, multi-agency Violent Crime Enforcement Teams (VCETs) have seen a steady increase in meth seizures and arrests since the low point in 2009. Seizures by VCET units went from 230 pounds in 2015 to 489 pounds in 2016 to 625 pounds in 2017 (Figure 6). It should be noted that VCET statistics include only those agencies funded by the Department of Public Safety Office of Justice Programs and do not include statistics for the State Patrol or local agencies unless they were involved in an operation with a VCET team.

“Is there more meth [than opioids]? Absolutely,” said Brian Marquart, DPS’s statewide gang and drug coordinator, who oversees VCET activity. In the past, meth seizures measured around three to five pounds per seizure, Marquart said. “Now it is 30-plus pounds of meth in a typical seizure. That’s ten times what it used to be that we are seizing coming into the state, and that’s just one seizure. We know that several more make it through.”

Hospitals: The cost of addiction adds up

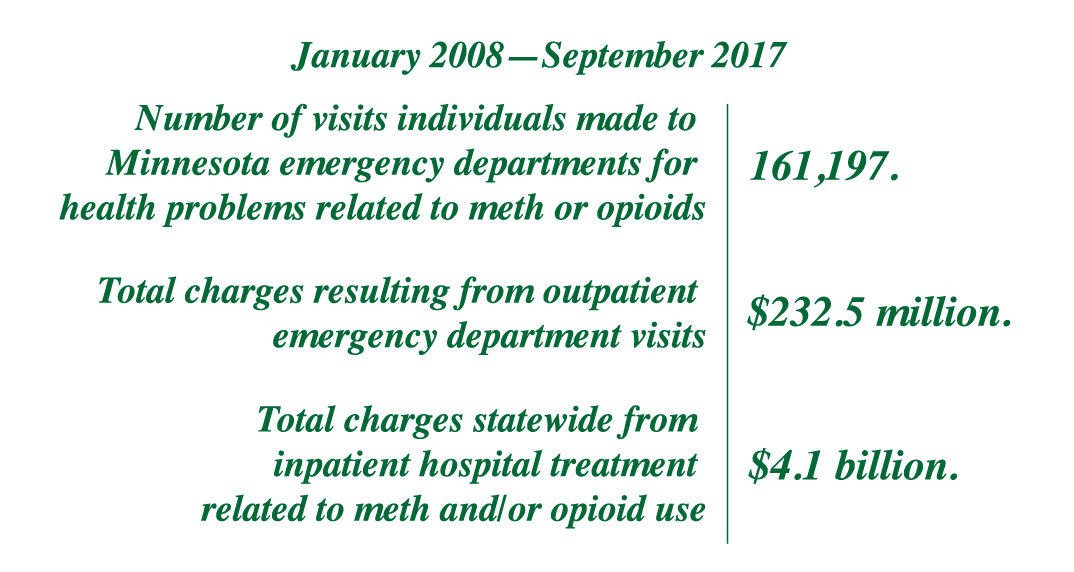

An analysis of data from the Minnesota Hospital Association shows that over a ten-year period between January 2008 and September 2017 (the latest data available), individuals with some variety of health problem related to meth and/or opioids visited Minnesota’s hospital emergency departments 161,197 times. Of that number, 82,509 were outpatient visits while another 78,688 resulted in admissions.

As far as the cost goes, the charges resulting from outpatient emergency department visits involving meth and opioids represented only a small fraction of total charges over those 117 months—less than 1%—but the dollar amount they represent is substantial: $232.5 million. Over the same time period, hospital admissions resulting from emergency department visits came to $2.4 billion, while total inpatient charges for admissions related to meth and/or opioids statewide came to a whopping $4.1 billion dollars over that time span. We did not look into substances other than meth and opioids; therefore, hospital costs related to the use of other substances will likely only add to the total.

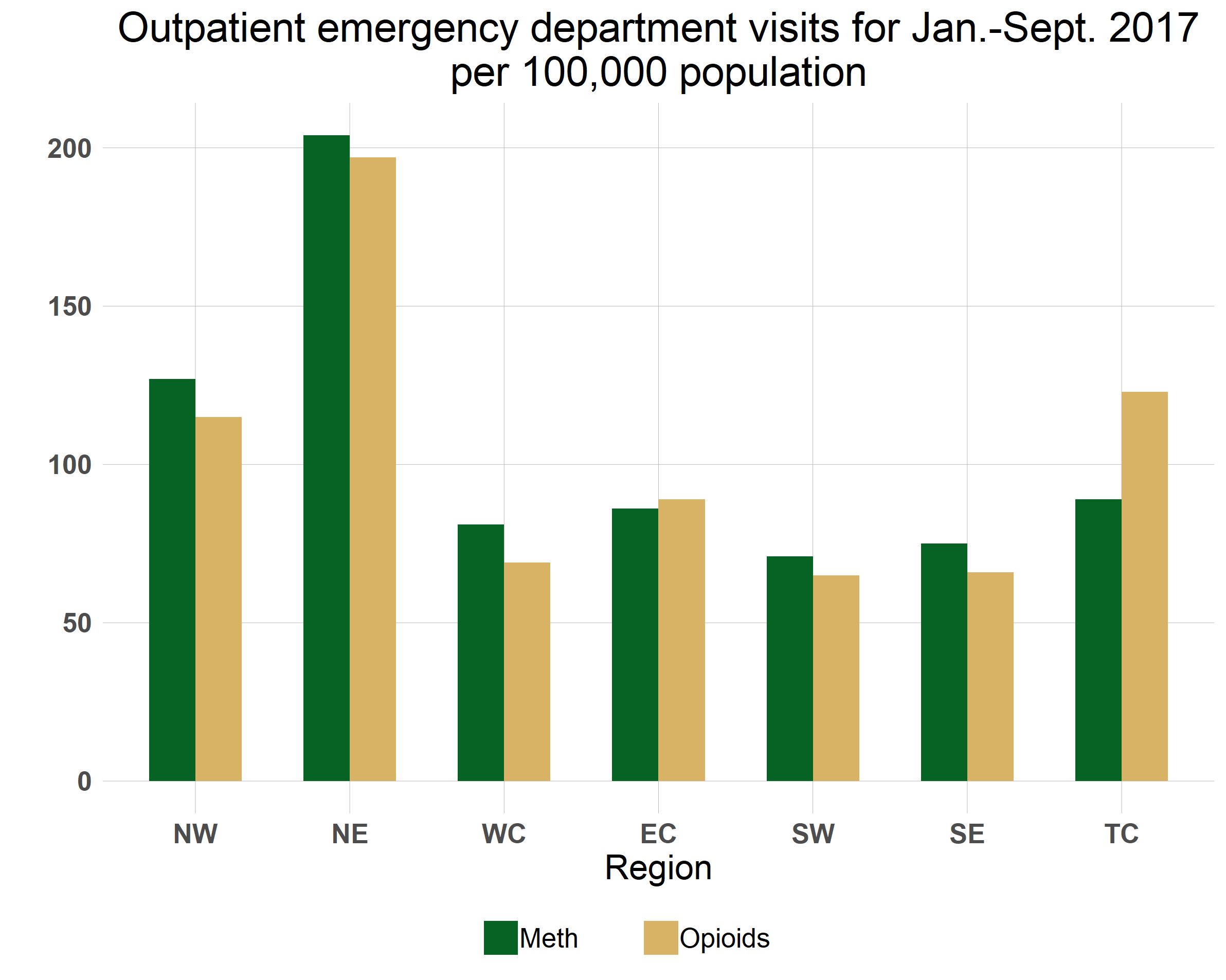

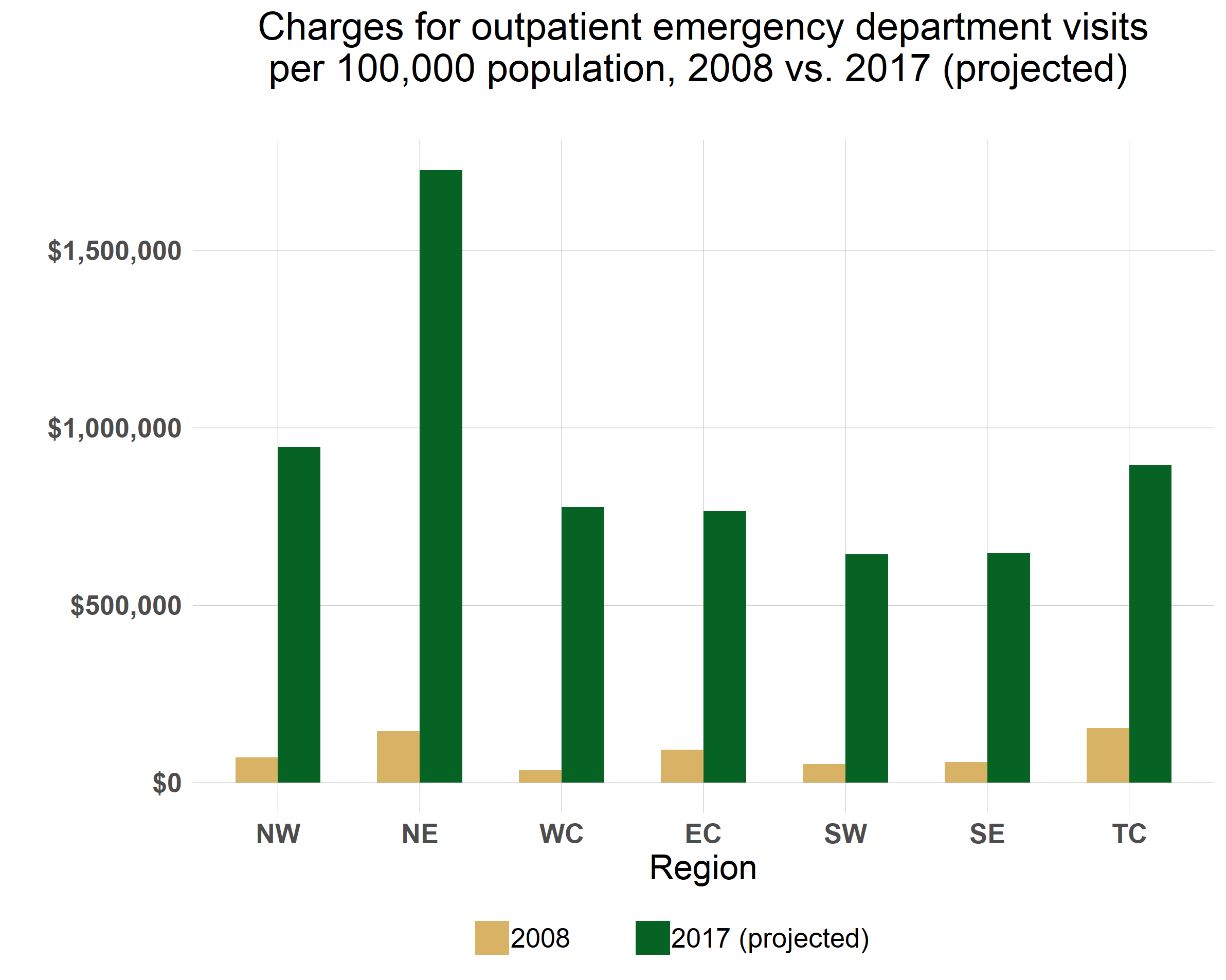

As the number of meth- and/or opioid-related emergency department visits mushroomed, so did the dollars spent on them. If we project out the data for 2017 to include the last three months of the year, total outpatient emergency room visits between 2008 and 2017 were up an average of 23% statewide, while charges for emergency room visits were projected to be up overall by about 114%. Emergency department visits involving meth and/or opioids, however, increased 337%, while charges were projected to increase 665%, from $6.2 million in 2008 to $47.6 million in 2017.

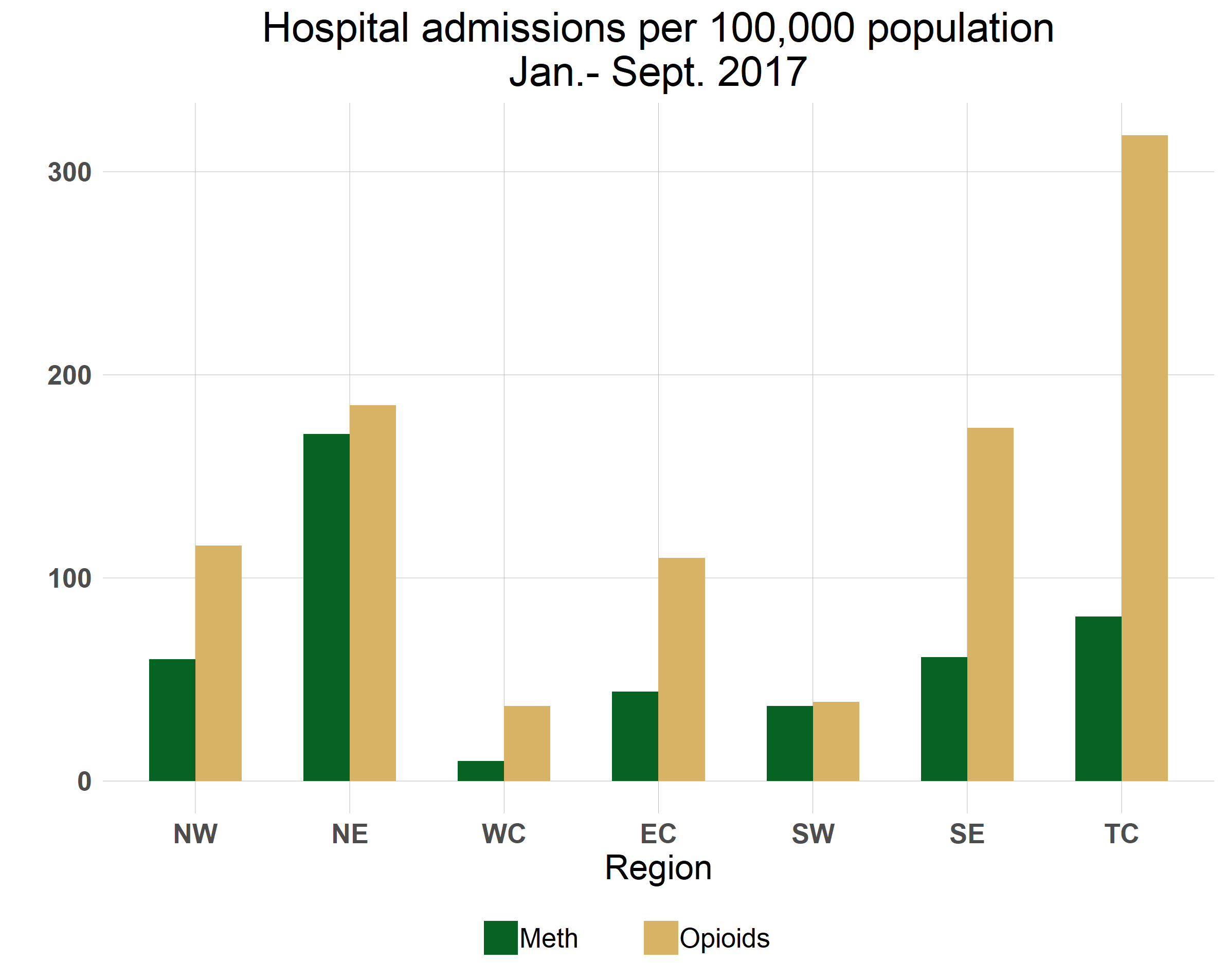

The impact on the state’s hospitals seems to vary quite a bit from region to region, however. The Twin Cities area sees the highest actual numbers in visits, admissions and charges related to meth and opioids. Charges for outpatient emergency department visits to hospitals within the seven-county metro area involving meth and/or opioids increased a projected 512%, from $4.3 million to $21.4 million. But when the data is adjusted to reflect population differences, hospitals in northeastern Minnesota experienced the highest emergency department use and highest charges for meth and/or opioid patients per 100,000 residents (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7 also shows that in terms of outpatient ED visits, meth is keeping pace with opioids and even surpassing it in all regions of the state outside of the Twin Cities. On the other hand, more of the admissions to hospitals involved opioid use than meth (figure 9), although note the almost equal rate of meth- and opioid-related admissions in northeastern and southwestern Minnesota.

The Minnesota Hospital Association acknowledges that their members in Greater Minnesota are seeing an increase in the use of meth among patients in their emergency departments.

“Hospitals and health systems across Minnesota are seeing an increasing and concerning trend in substance abuse emergency visits across Minnesota,” said Dr. Rahul Koranne, chief medical officer of the Minnesota Hospital Association. “To respond to the opioid epidemic specifically, Minnesota physicians are decreasing the number of opioids we are prescribing in clinics and emergency rooms, but we have more work to do in close collaboration with our community partners, including the state of Minnesota, counties, social service agencies, law enforcement and recovery advocates.”

Workforce: The primary barrier to access

The need for workers is acute in many areas of health care and human services, whether urban or rural, and drug treatment is no exception, but rural areas face a disadvantage in attracting workers.

“Regardless of what the most popular drug is, we’re always faced with the workforce shortage,” says Charles Hilger, vice president of MAT (medication-assisted therapy) services at Meridian, a for-profit chemical dependency treatment and mental health provider based in New Brighton. Meridian has facilities around the state. Attracting counselors and other staff is the major challenge right now.

Medication-assisted therapy, which is currently used to treat opioid and alcohol addiction, uses medications to help patients curb their withdrawal symptoms to prevent relapses. The Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment (a treatment organization not associated with Meridian) operates ClearPath, an MAT program in Duluth that is currently treating about 500 patients, says Hilger, while Meridian Behavioral Health’s MAT program in Brainerd, Valhalla Place, is seeing another 400. About 15% to 20% of those Brainerd patients, though, are in fact people coming from Duluth because the community does not have enough counselors to fill the needs of the treatment centers there, Hilger says. At the same time, other parts of northern Minnesota have no MAT providers.

Even the larger cities in Greater Minnesota, like Bemidji and Mankato, don’t have the workforce, Hilger said.

“The city of Bemidji would support something like this, but there are not enough counselors,” Hilger said. “The ratio of patients to counselors is 50 to 1.”

When it comes to the use and abuse associated with different drugs, the abusing behavior can look quite different from drug to drug, but the addiction itself is essentially very similar, says Hilger, who has 20 years’ experience in substance use disorder treatment and has worked across the country. “Behind the substance use is trauma, mental health issues, family issues, legal issues,” he says.

In 2017, the Minnesota legislature passed the Substance Use Disorder Reform Act, or SUD Reform. The philosophy behind this legislation, according to the DHS, is to move the system from an “episodic model,” (i.e., 28 days and you’re done) to a longer-term longitudinal model.[16] A key component includes streamlining the process of getting people into treatment. Under the traditional “Rule 25” system, a person seeking out treatment that would be paid for with public assistance must go through several assessment and approval gates, starting at the county, before getting into a treatment program. The delay between the first assessment and finally entering treatment, often up to a month or two, provides many opportunities for a person to drop out of the process: relapse, leaving the area, being arrested or dying. The new system,[17] which goes into effect July 1, 2018, allows individuals on public assistance to go directly to a qualified provider for assessment and start a course of treatment right away, skipping several steps (although counties will still determine an individual’s financial eligibility for services).

This new legislation begs the question, of course: What to do in rural areas where there are few or no treatment centers?

Counties will have a two-year phase-in period: they can continue their assessment programs and also choose to be certified as qualified assessment programs themselves. They will, however, eventually have to have the properly trained and licensed staff to do so.

So where to find the licensed alcohol and drug counsellors (LADCs) who will be required under the new system? An LADC level of education and experience will be required to provide several of the new services that are becoming available with SUD Reform. One new service, treatment coordination, will not require an LADC license, while another service, withdrawal management, will require a number of different staff, including LADCs.

In a 2017 article from the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development looking at the pipeline of mental health professionals and practitioners, it showed that between 2007 and 2014 only about 60% of the people graduating from Minnesota LADC programs actually went on to become licensed.[18] The other 40% diverted off into other forms of work.

But while the problem is critical right now, the strong demand is helping to stoke the supply line. Jennifer Londgren is program coordinator in the Alcohol and Drug Studies program at Minnesota State University Mankato, which offers a bachelor’s degree in alcohol and drug studies and where students are required to complete their internships (880 hours of experience supervised by an LADC) to get their degree. After that, becoming licensed is one more test.

“It will be a couple of years based on the number of students coming in, but right now our program is booming,” says Londgren.

Until those students graduate, though, there is definitely a shortage.

“I receive at least two emails a week [from providers] looking for available interns,” Londgren says.

The drug epidemic, coupled with a wave of retirements from baby boomers leaving the treatment field, is increasing demand for LADCs, which is in turn eliminating some of the most common hurdles to expanding the treatment workforce.

To become licensed, students in most mental health and drug treatment fields must complete internships, clinicals or practicums. In the past, students had to search for a provider that would allow a qualified staff person to supervise the student for the required number of hours, and students often had to pay for that supervisor’s hours themselves since not all third-party payers would reimburse for hours spent supervising. Now providers are actively searching for students, paying for their training, and paying them as well, Londgren says. And once they become licensed, their job prospects look bright: most of her graduates are hired where they interned, and one treatment center recently offered a student of hers a starting salary over $60,000 for a bachelor’s degree.

This upward pressure on salaries is good for counselors but hard on providers, especially rural ones, where clients are more likely to be on public assistance.

Reimbursement rates are critical. When Chuck Hilger began in MAT programs in 2003, for example, the reimbursement rate was $12.60 a day; today it is $13.39—an increase of less than a dollar over 15 years—and he is required to provide more services, he says. Given the pay the current workforce shortage is demanding, “reimbursement is not keeping up,” he says.

Some things being discussed to help attract workers to rural areas besides more attractive pay are loan forgiveness programs. Allowing rural clients to consult with a treatment provider in the city via new telehealth services will help, too, Hilger says.

Substance Use Disorder Reform also approved the use of peer recovery counsellors, people who have a substance use disorder who have been through treatment and have now gone through the educational and certification process to provide recovery services to others. The state has been developing the peer recovery services program using grant dollars; now the program is waiting on a decision by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare on whether peer counsellors can be paid using Medicaid dollars.

Intervention: Local communities, local solutions

If there is any good news to be found in the current addiction epidemic, it is that we are examining our attitudes and understanding of drug policy, treatment, and prevention. We collected three examples of communities acting creatively to make the system work better.

Intervention: Blue Earth County’s Yellow Line Project

Many counties in Minnesota and across the nation face a relentless cycle: people who need chemical dependency treatment and/or mental health services ending up in jail, week after week, year after year.

When law enforcement officers encounter a person posing a threat to himself or others, the typical pattern is to put the person in a jail cell, wait for the criminal justice system to take its course, then release him, only to bring him in again in the near future.

To break this cycle, Blue Earth County Human Services, the county’s law enforcement agencies and the county attorney’s office have developed the Yellow Line Project. Its goal: to get to the root of the person’s problem, identify what keeps him reoffending, and addressing that.

The Yellow Line Project involves making a social worker available at the door of the jail or out in the community to assess individuals for chemical or mental health issues as needed by law enforcement. If those issues are found and if a viable treatment plan can be formulated, the law enforcement officer will then make a decision on what charges will or will not be filed against the individual.

The important component is that the social worker can then schedule the person to meet with a community-based coordinator as soon as possible, preferably the next day. At that meeting, the coordinator talks with the person to figure out the best form of treatment going forward.

The county’s human services staff have found that the highest correlation with success so far is if and how soon the person meets with that community-based coordinator so they can get started on a program, says Angela Youngerberg, assistant human services director for Blue Earth County. They have found so far that people who met with the coordinator within the first one to two days had a 70% success rate, while those who had a delay in meeting or didn’t meet at all with the coordinator had only a 30% success rate.

Without the Yellow Line Project, offenders who are brought in with chemical or mental health issues would very often not see any kind of treatment until it was ordered by a judge at their first court appearance, which could be one to two months later. By that time the momentum is lost.

There is something about being offered an opportunity for treatment right away, when individuals are at their lowest, says Youngerberg, that is very motivating for them. People who are charged are still held accountable, but when they do eventually make their first court appearance, those who are already engaged in treatment are often standing before the judge in much better shape than they would have been.

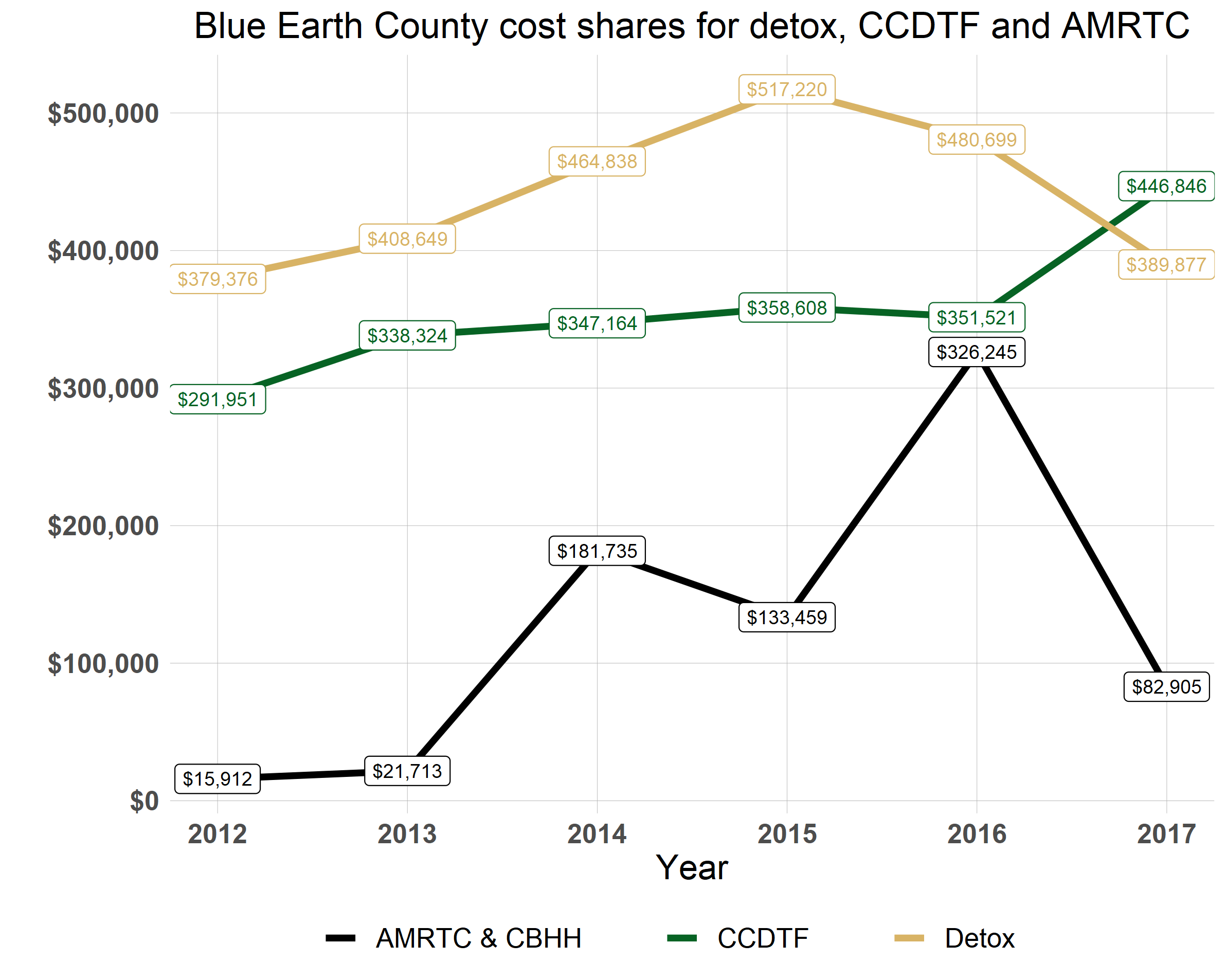

The impact of the Yellow Line Project is reflected in the county’s human services budget as well. A chart of Blue Earth County’s share of spending for detox services, the state’s Consolidated Chemical Dependency Treatment Fund and the Anoka Metro Regional Treatment Center (AMRTC) between 2012 and 2017 shows the dramatic effect the Yellow Line Project had in its first year (Figure 10). Based on the previous years’ trends, the county had budgeted $510,000 for detox services, $340,000 for its share of CCDTF expenses, and $305,000 for its share of the cost of sending people to AMRTC. Expenses for AMRTC had risen considerably since 2013 when legislation was passed requiring that incarcerated individuals who are found through a court-ordered evaluation incompetent due to mental illness be sent to AMRTC for treatment.

As the chart shows, detox expenses dropped by a quarter, while CCDTF expenses went up by 30%—if any line must increase, that’s the line you want to see go up, said Youngerberg, since that is money spent on long-term treatment. Meanwhile, expenditures for AMRTC came to $82,905, just 25% of the previous year’s expenditures.

Early intervention is another accomplishment that surprised county officials, and they’re hoping it is paying off. If someone has been brought in “because they made a bad decision on a Saturday night,” the screener will get to the bottom of the issue. A felony conviction or just an arrest record can lead to lifelong ramifications for education, career and income, a concern in a county with a large college-age population.

Phil Claussen, Blue Earth County Human Services Director, attributes a good part of the program’s success so far to the good relationships his department has built with county law enforcement, the county attorney’s office, probation, and hospitals.

“The public thinks we’re fully integrated,” says Youngerberg, but that was not the case. Developing the Yellow Line Project involved a great deal of communication and trust-building among the different groups, which they now believe is paying off.

CHI St. Gabriel’s Health and St. Gabriel’s Foundation: Morrison County Prescription Drug Task Force

It was the nursing staff at CHI (Catholic Health Initiatives) St. Gabriel’s emergency department who first raised the alarm about the extent of the prescription opioid problem in Little Falls. The ER was inundated, says Kathleen Lange, director of St. Gabriel’s Foundation. When they investigated, they found that early refills were common, people were still on prescriptions long after they should have been off, 100,000 opioid pills were going out of Little Falls’ pharmacies each month, and “nobody questioned it.”

With a grant from the Minnesota Department of Health, community partners including the hospital; law enforcement; Morrison County Social Services; South Country Health Alliance, the county’s public health provider; Coborn’s pharmacy; and others formed the Morrison County Prescription Drug Task Force.

The initiative’s strategies have focused on changes within healthcare, including new prescription policies, and improved community collaboration and communication. At the heart of the program is the controlled substance care team made up of physicians, nurses, a social worker and a mental health care coordinator.

To start, the team identified 500 individuals who were on large doses of prescription opioids for either chronic pain or unknown reasons. What they found were people who were either addicted or who were selling their pills, including a 75-year-old woman who was selling her pills to pay the rent.

Social workers have been key in working with patients, says Lange. “They can get to the root of the problem.” Since the program started, the number of opioid pills going out of Little Falls pharmacies has decreased 23%.

The program also offers medication-assisted therapy (MAT) to treat addiction. So far the program has seen 453 of their original 500 patients tapered off of opioids completely, with savings to Medical Assistance calculated at $3.8 million. That doesn’t include the others who are tapering down but are not completely off opioids yet.

From the prevention side, task force members are giving talks in the community and working with schools to warn students about the dangers of taking prescription opioids for sports injuries. Building good relationships with community partners and sharing information is key, says Lange. Their partnership with law enforcement has been particularly important. Not only are officers on the front lines of the drug epidemic, they can share information on individuals that the clinic and other health care providers can’t due to HIPAA regulations.

They still face some problems, Lange said, including a new issue of young people who come in with withdrawal symptoms from opioids or heroin and can’t afford the medication-assisted therapy but also don’t qualify for Medical Assistance. So far, the Foundation has set up a charge account at pharmacies to cover the cost of the medication, but it’s not a permanent fix.

Also, law enforcement is telling them that the meth issue in the county is going to be bigger than opioids. “We just don’t know,” Lange said.

And finally, the program is still operating on a grant from the state legislature, but they are working on how to make the program sustainable if and when those grant funds run out.

For more information: Prescription Drug Task Force Video

Sanford Bemidji Medical Center: First Steps program

First Steps to Healthy Babies in Bemidji got started when nurses at Sanford Bemidji Medical Center began noticing an increasing number of pregnant women coming in with substance use disorder and no prenatal care. The danger was that babies born to addicted mothers often suffer from Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Following the traditional pattern, the mother would deliver her baby, the baby would be put under a 72-hour hold by social services, and then be placed in foster care.

With a grant from Prime West, Sanford Bemidji Medical Center started a program that provides education, support, case management, counseling and medication-assisted therapy to help pregnant women control their addictions while they are pregnant and afterward.

“[Staff] recognized more and more moms and babies were being separated due to drug use,” says Alyssa Bruning, a registered nurse involved in the program.

The mothers need extra support and often arrive with mental health needs besides the substance use disorder. The program’s social workers provide case management and a connection to social services the mother may have needed but wasn’t accessing before. Part of their help may include incentives for participating, like phone cards, gas cards and help with rent and diapers.

“So many women don’t have any support, unlike a typical person with a family,” says Bruning. “When you don’t have transportation, it can take all day to get to a medical appointment.” When people have a lot of responsibilities and not a lot of resources, that creates stress, and stress can trigger a relapse. Removing that stress helps.

There is no medication-assisted therapy for meth addiction, but the program does help clients find traditional chemical dependency treatment, Bruning says.

What is needed now is public health awareness, says Bruning. Public health awareness campaigns changed how we think about alcohol use and smoking during pregnancy. The same could be done with drugs, says Bruning, but at the same time the message has to be that if you are using, it doesn’t make you a monster.

“Pregnant mothers with addictions deal with a lot of shame and fear. We need more programs focused on pregnant women and compassionate support. It’s a disease. It’s not okay to use drugs, but you can get help for that.”

Addressing the issue: The Minnesota Hospital Association

According to the Minnesota Hospital Association, the opioid epidemic is a high priority for hospitals and health systems throughout the state. Actions hospitals and health systems are taking include:

- Significantly limiting opioid prescriptions in emergency departments.

- Early recognition of overdose, responding with Narcan in communities and emergency departments.

- Working to decrease both the amount of opioids prescribed and the variation in prescribing among providers in clinics. MHA is partnering with the Department of Human Services in rolling out the prescribing guidelines developed by the Opioid Prescribing Work Group to MHA

- Reviewing clinic patients who are on long-term opioids that are not or no longer medically effective to identify alternatives, tapering them off or getting them into treatment for addiction.

- Educating providers and patients regarding opioids, alternatives and addiction treatment.

- Exploring alternatives for pain management and calling on insurers to cover these alternatives.

- Encouraging more physicians to provide medication-assisted therapy (MAT) with Suboxone or office-based opioid treatment (OBOT).

- Working to integrate the state’s prescription monitoring program data with electronic health record systems.

- Working with partners to destigmatize substance use disorder, which is a treatable medical condition, and working to get patients who need treatment into treatment, including with the use of Medication Assisted Treatment.

- Partnering with community organizations on unique prevention efforts. An example of a model would be the program created by CHI St. Gabriel’s Health. More Minnesota hospitals will be replicating this model in the next year as a result of state grants. [19]

While these particular steps target opioid use, many of them can also be translated to the problem of meth, the Minnesota Hospital Association stated.

“The work our members are doing to coordinate with local partners—whether it be treatment providers to get patients with substance use disorder into treatment and law enforcement with respect to the flow of meth into communities—would carry over to meth and other drugs,” said Wendy Burt, vice president for communications and public relations.

Where does it end?

The difficult truth about the drug epidemic in Minnesota is that once the problem of prescription opioids is addressed with special policies and targeted programs, the more difficult nut to crack—endemic substance use disorder and its embedded, long-term causes—is still out there. The people who need help will be harder to help and their issues more complex than those who became hooked on opioids by accident, through an unfortunate prescription. And while the death count from opioids is much higher and is indeed an emergency right now, the number of lives blighted and the dollars spent in dealing with the fallout from addictions to other substances are still adding up.

While recent policy changes may have helped boost the stats of people accessing treatment, the growth in overdoses, overdose deaths, hospitalizations, emergency room visits and county social service budgets indicates a broad problem of addiction that won’t end when the opioid crisis ends.

Recommendations

Addiction: First, look at the opioid crisis as just one part—a major part but only one part—of the overall addiction crisis.

- We need better use of the information we have. In the process of researching, we found officials and leaders were well aware of the opioid issue, but often only those directly involved at ground level were aware of the extent of meth use in Greater Minnesota.

- Addiction in general is a major issue for our Native American communities. We need better data, better information, better communication, and a focused and intentional examination of the causes behind this ongoing problem.

- As one drug goes out of favor, there will always be a market for the next drug of the month unless we can work on demand, and that means prevention.

Workforce: Although demand is filling college programs and thereby making the supply of LADCs less of an issue in the near future, that mostly applies in urban areas. Rural areas will continue to struggle to find workforce.

- Look to innovative programs in our colleges and universities that streamline the licensing process (or make it more difficult to skip that step).

- Enact policies that help both grow-your-own efforts in postsecondary programs in rural areas and aggressive efforts to retain workers.

- With SUD Reform going into effect soon, there may be a large number of county and healthcare staff already active and experienced in drug treatment programs who may not have the right credentials now but who would be good candidates to staff the new programs if they receive the required training. This could be an excellent opportunity for the state, counties and private providers to assist this pool of willing workers in getting their licenses or other credentials, especially if they plan to continue working in their current communities.

Treatment: Continue the focus on solutions that promote long-term recovery rather than a short-term fix.

- Analyze the results of new innovative intervention programs like those highlighted here and help communities statewide replicate them.

- Expand drug and mental health courts and look to other innovative diversionary programs that keep people who need treatment more than jail out of jail.

- Continue to expand access to supports for recovery like housing assistance and ongoing counseling for those with chemical dependency issues and mental illness. A little support can mean the difference between relapse and staying on the right track.

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Drug Overdose Death Data.

[2] Washington Post, “Opioid abuse in the U.S. is so bad it’s lowering life expectancy. Why hasn’t the epidemic hit other countries?” Dec. 28, 2017.

[3] Centers for Disease Control, “Health, United States, 2016,” May 2017, p. 153.

[4] Stephen Montemayor, “Powerful new drugs require new procedures to protect police,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, Oct. 25, 2017.

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Drug Overdose Death Data.

[6] Minnesota Department of Health, “Drug Overdose Deaths Among Minnesota Residents, 2000-2016,” 2017, p 17.

[7] Allison Bond, “Why fentanyl is deadlier than heroin, in a single photo,” Stat, Sept. 29, 2016.

[8] Greta Kaul, “While Minnesota authorities focus on opioid abuse, meth is making a comeback,” MinnPost, June 7, 2017.

[9] “Parental drug abuse the most common primary reason children are placed in foster care,” MN Department of Human Services, Dec. 20, 2017.

[10] Chris Serres, “Opioid crisis strains Minnesota’s child protection system,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, Jan. 20, 2018.

[11] Foray, Ariadna, “Substance use during pregnancy,” National Institutes of Health, May 2016.

[12] Conners, Nicola, et al., “Children of Mothers with Serious Substance Abuse Problems: An Accumulation of Risks,” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Vol. 30, 2004, p 94.

[13] North Dakota Department of Health, “New Mother Fact Sheet: Methamphetamine Use During Pregnancy,” Oct. 2002, www.ndhealth.gov.

[14] Conners, Nicola, et al, p 86, 95.

[15] Minnesota Public Radio, “Big, recent pot busts get cops’ attention in Minnesota, North Dakota,” Feb. 13, 2018.

[16] MN Department of Human Services, “Substance Use Disorder Reform—Clearing Up Some Mistaken Information,” Sept. 2017.

[17] MN Department of Human Services, Substance use disorder reform.

[18] Alessia Leibert and Teri Fritsma, “Filling the Mental Health Pipeline,” Minnesota Economic Trends, Sept. 2017.

[19] Minnesota Hospital Association. For more information, go to https://mnhealthycommunities.org/opioid-crisis/