A report in partnership with the Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Marnie Werner, Vice President, Research, Center for Rural Policy & Development

Thad Shunkweiler, LMFT, LPCC, Associate Professor and Director, Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University Mankato

Tracie Rutherford Self, Ph.D, Assistant Professor, Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University Mankato

Click here for a pdf version of this report.

Click here for a two-page summary of this report.

February 2023

Rural residents have dealt with diminishing access to healthcare services for decades, largely because the continuous increase in the costs of providing services makes sparsely populated rural communities less economically feasible to serve than densely populated urban areas. This problem applies just as much to mental health services as any other aspect of healthcare in the United States. But now more than ever, as the demand for mental health services increases everywhere, mental health providers are struggling to hire and hang onto workers. In rural areas, where demand is on average higher and the supply lower than in population centers, providers and their clients are especially feeling the strain of the current workforce shortage.

Based on a survey and a series of interviews conducted in the fall of 2022 by researchers at the Center for Rural Behavioral Health at Minnesota State University Mankato, it has become apparent that the mental healthcare workforce shortage is being aggravated by a handful of quite specific and identifiable problems around graduating workers, recruiting them, and keeping them once they are hired. Bringing these challenges to light and solving them may not fix the workforce shortage completely—the wave of retiring Baby Boomers plays a significant part in the shortage—but resolving these issues could help with the supply of mental healthcare professionals and workers going forward, especially in rural communities.

What is rural?

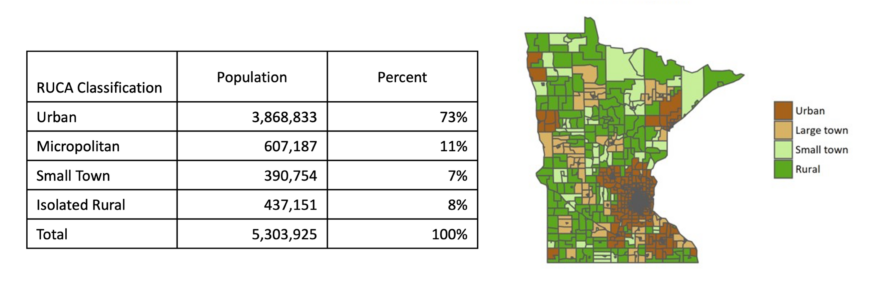

According to the Minnesota State Demographic Center, Minnesota is a little more rural than average.[1] More than 25% of the state’s population lives outside of metropolitan communities, defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as communities of greater than 50,000 people, compared to 19% of the U.S. population overall.[2] Another way to look at the distribution of population around the state is with Rural-Urban Commuting Areas. From dark brown to dark green, the areas indicate population density and commuting patterns around the state.

Table 1. The Rural-Urban Commuting Areas divide the state by population density and commuting patterns. MN Department of Health.[3]

The issues of mental health services in rural areas

Rural communities deal with additional health disparities compared to their urban counterparts, including higher rates of heart disease, cancer, motor vehicle crashes, and opioid overdoses.[4] Besides physical health problems, however, rural residents also experience higher rates of mental health symptoms. Negative attitudes toward mental health issues in some rural communities and the challenges that long distances to services create[5] all compound the problem of unmet need in rural communities.

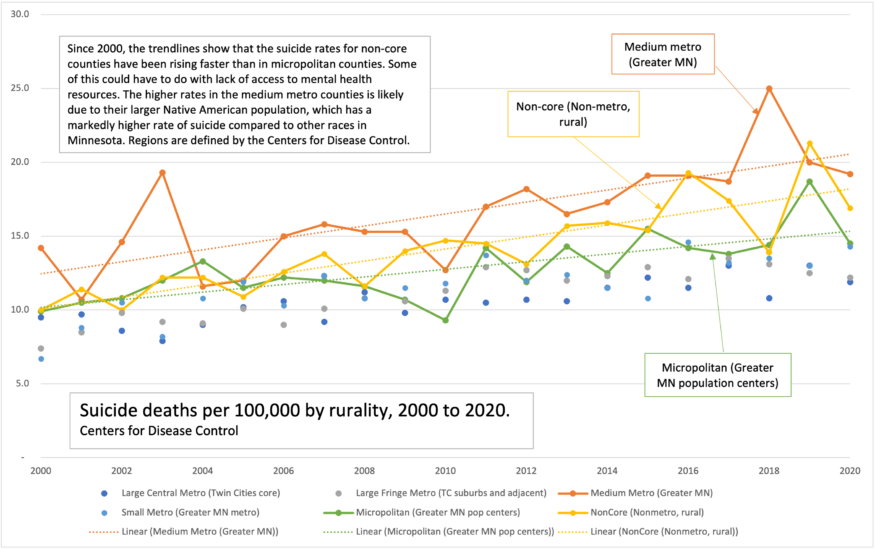

Unmet need is difficult to measure, however—it is hard to track who needs services but is not getting them—but we do know Minnesota is experiencing an unprecedented demand for mental health services, especially following the pandemic, and that rural Minnesota is being hit especially hard. As Figure 1 shows, since 2000, the rates of suicide in rural Minnesota are higher and rising faster than in the Twin Cities or the state’s other population centers. In 2021, suicide accounted for two thirds of gun deaths in Minnesota, and the largest proportion of those deaths were in the state’s most rural areas.[6]

Figure 1. Suicide rates since 2000 have been higher and growing faster in rural areas of Minnesota than in urban and suburban counties, one indication of unmet need for mental health services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 2022 Minnesota Student Survey, which measures the health and wellbeing of Minnesota’s fifth-, eighth-, ninth-, and eleventh-grade students, indicated that 29% of students reported long-term mental health problems, an 11% increase since 2016 and the highest level since the survey started in 1989.[7] When broken down geographically, however, the eighth-, ninth-, and eleventh-graders in Greater Minnesota averaged somewhat higher than those in the Twin Cities, 34% vs. 28% respectively.

Early intervention is key when dealing with mental health concerns. Symptoms of mental illness don’t care when the therapist is available, and undertreated or untreated disorders don’t resolve on their own. Without treatment, mental health challenges often progress to worse outcomes like drug addiction and suicide. When the issues become challenging enough, the person will very likely end up in an emergency department or county jail, especially in rural counties with few alternatives. There they consume valuable resources to treat what could have been an out-patient issue.

Epidemic proportions

Looking at mental health services in rural areas “starts with talking about poverty in rural areas, the loneliness epidemic in rural areas, the stigma that we have, not only in greater Minnesota, but in our entire state around talking about mental health and mental health care,” said Maggiy Emery, interim executive director of Protect Minnesota, a non-partisan non-profit working to end gun violence. “If we want to address the suicide epidemic as it exists in our state, we really have to start there.”[8]

Three factors aggravate this unmet in rural areas: accessibility, availability, and acceptability.[9]

Accessibility

Accessibility is defined in this case as having the resources to obtain mental health services. Mental health issues are often compounded by issues related to economic instability and an inability to afford mental health services, and rural residents experiencing increased mental health symptoms have a substantially higher likelihood of becoming economically fragile compared to their counterparts in urban communities, leading to access issues due to financial constraints.[10]

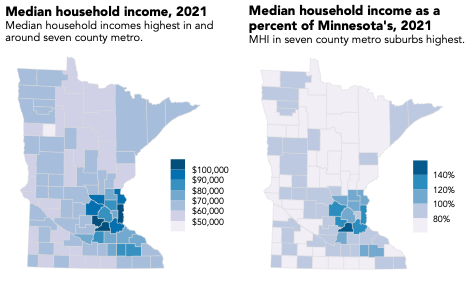

According to the Minnesota Department of Health, income is often linked to health status. [11] The state median household income in 2021 was $77,706 in 2021.[12] In that year, nearly every county outside the Twin Cities seven-county area (plus Ramsey County) had a median income below the state median income.[13]

Figure 2. The median household incomes of most counties in Minnesota are lower than the state median household income. Atlas of Minnesota Online

Rural Minnesota’s lower cost of living can make up for this lower income, but the higher average age of Greater Minnesota’s population, and the fact that rural Minnesota’s small employers are less likely to provide health insurance for their employees contribute to the greater use of Medicare, Medicaid, and MinnesotaCare in rural areas.[14] These public programs are not accepted by all providers and may lead to longer wait times if and when the client does find a provider.

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) also reports that mental health centers are sparser in rural regions than in urban and suburban communities,[15] leading to longer driving distances, which can be especially troublesome for people with limited ability to travel, [16] whether because of their finances (they don’t own a car or can’t drive themselves, for example) or the severity of their symptoms makes long-distance travel difficult.

Availability and a Lack of Providers

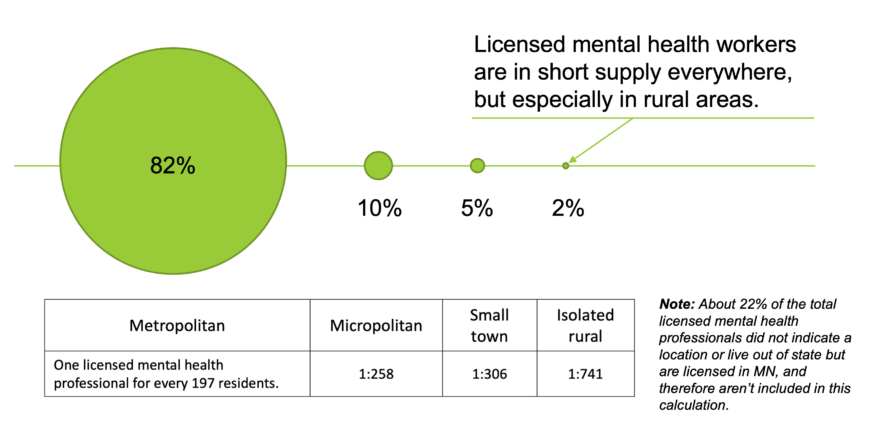

For individuals experiencing symptoms of mental illness, a lack of places to turn to can compound feelings of isolation, but as Figure 3 shows, the state’s licensed mental health workforce is not even distributed. While in metropolitan areas there is one licensed mental health provider for every 197 residents, that ratio goes up as the population density goes down, with 741 residents for every one provider in the most rural areas.[17] A full 80% of counties qualify as mental health provider shortage areas, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration.[18]

Figure 3. In December 2022, 82% of licensed mental health providers[19] lived and/or work in the Twin Cities or one of the state’s larger cities. The licensed provider-to-client ratios vary considerably around the state. MN Department of Health.

In the past decade, the number of hospitals with outpatient psychiatric and detoxification services in rural Minnesota has declined 11%.[20] Rural and small-town providers are also closer to retirement and will leave the workforce at a faster rate than their metropolitan counterparts. Of those professionals who serve Greater Minnesota, the median age is 63, compared to 56 for those practicing in urban settings.[21] In addition, rural mental health practitioners with full schedules also contend with providing care for a wide array of issues, making them generalists who may or may not have the time or opportunity for in-depth instruction in specialty areas like suicide prevention.[22]

This lack of available services leads to long wait times for appointments and limited hours of availability (for example, only offering appointments during regular work hours). Availability can be a particular burden for rural populations without access to a car, given the lack of public transportation available in rural communities and the growing need to travel long distances to access services found only in population centers.

Acceptability and overcoming stigma

Finally, rural individuals with mental health symptoms face the challenge of acceptability and stigma around accessing mental health services in their communities. These barriers may look like a lack of trust from families and a fear of being labeled as “crazy.”[23] Unfortunately, the denser social networks in rural communities, where everyone seems to “know each other’s business,” can also inhibit individuals, making them hesitant to seek mental health services and increasing the perceived level of stigma in their community.[24] Self-isolation, insular community behaviors in more isolated areas, and a general mistrust of the medical, and especially mental health, community can all create barriers to services.

Further, rural communities, which have a history of self-reliance, are much less likely to seek out assistance from outside the community, instead preferring to rely on family or others in their social circles.[25] A related problem is that of “dual relationships,” where one person has multiple roles in a community, for example, the local therapist who treats neighbors may also be a mother who volunteers with those same neighbors at their PTA or church. The smaller the community, the more inevitable these kinds of relationships become and may prohibit some from seeking out care.[26]

The most concerning issues around acceptability, however, are serious mental health symptoms and suicide. Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death nationally but the eighth leading cause in Minnesota.[27] A recent report by the Minnesota Department of Health noted a decrease in the suicide rate for youth suicide in 2022, but there was a noted increase in the suicide rate for elderly individuals, who make up a larger portion of the population in rural communities.[28]

Despite the decline in 2020, suicide in Minnesota accounted for over 800 deaths in 2021. A CDC analysis also found that while the national suicide rate declined in 2020, that decrease was for individuals who identify as white. There was a sharp increase among people of color and other marginalized populations (LGBTQ+, people with disabilities), [29] a fact important to keep in mind since the primary population growth in Minnesota over the next fifty years is expected to be in communities of color. In addition, both rural Minnesota and the metro area receive a high number of refugees, who have likely suffered trauma in their travels here and may now be dealing with undiagnosed issues as well.

Recruit, Retain, Sustain: Finding mental healthcare workers for rural Minnesota

Within this context, the great challenge of providing mental health services in rural areas is finding and training the people to fill those provider roles. To better understand the underlying causes of these challenges, we conducted interviews with representatives from seven clinics around Greater Minnesota and surveyed a number of the educational programs in the state that provide degrees leading to licensing in various mental health fields. Several themes around recruitment, retention, and training emerged, as did insights into the impact of the workforce shortage on those who need services.

Help wanted

“We’ve had very minimal luck in getting anyone who is fully licensed to move and come work up here.”

— Annmarie Florest, CEO, Range Mental Health, Virginia, MN

While the behavioral health workforce has always been challenging to maintain, the treatment gap between those who need care and those who are trained to provide it has never been larger than right now, especially for residents in Greater Minnesota’s communities. The clinic representatives interviewed attributed the cause of this growing gap of unmet need to the recent increase in demand for mental health care, which has caught nearly every clinic off guard.

“Mental health issues in our community have skyrocketed,” said Andrew Larson, clinical director and owner of the NorthStar Counseling Center in Hutchinson, MN. “Each year I say there is no way we can continue to be as busy as we are, but each year we get busier.”

In every interview from clinics as far north as the Iron Range to the southern parts of the state, the message is the same: It’s nearly impossible to hire mental health professionals to serve rural communities.

“The challenge that we face most is the pool of candidates we can choose from, which is often a pool of no one,” said Hillary Emerson, director of human resources for Northern Homes Children and Family Services in Grand Rapids, MN.

Probably the primary reason for the lack of applicants is the fact that it’s not easy to get clinicians to move to Greater Minnesota. Research[30] indicates that the further one moves from urbanized areas, the more difficult it is to hire licensed healthcare professionals: “Geographic distance from standard metropolitan statistical areas (SMSA) predicts an increase in difficulty of hiring, specifically, the measured difference shows approximately a 3% increase in difficulty of hiring for every 10 miles a social service program is from SMSAs.”[31]

Clinics across Greater Minnesota report clinical positions that can remain unfilled for more than two years. Organizations have tried several strategies to entice professionals both young and old to leave the metro area to work in Greater Minnesota, but none of the interviewees could identify a consistently successful recruitment model. Clinics reported offering flexible work schedules, work-from-home telehealth options, and free clinical supervision for licensure. With no applicants even applying, however, the incentives offered have had little effect.

Jon Schlenske, CEO of Southern Minnesota Behavioral Health in New Ulm, recalled an interview with a recent mental health counseling graduate where he asked what it would take for this clinician to work for their organization in southwest Minnesota. “The candidate’s response [was] ‘$100,000,’” Schlenske reported. “These types of demands cannot be met by any clinic, let alone a small non-profit in rural Minnesota who serves everyone, regardless of their ability to pay.”

To combat this challenge, the state of Minnesota, through the Minnesota Department of Health, offers student loan forgiveness programs to incentivize the development of rural practices. For mental health professionals who serve at least three years in a rural area, the state will provide $33,000 ($11,000 annually) for student loan repayments. The interviewees, however, noted that while incentive programs like student loan repayment may attract some professionals to serve rural communities, loan forgiveness by itself is not enough to attract professionals to rural sites or, in fact, attract potential students to the field.

“Clinicians will ask about it (Health Care Loan Forgiveness), so it’s on their minds, but I don’t think it’s what makes a final choice for them on taking the job or not,” said Emerson.

“What can we do to get you to stay?”

“Rural mental health clinics offer great training and first-job opportunities. However, many clinicians get their training and relocate to non-rural settings.”

—Jin Lee Palen, Executive Director, Minnesota Association of Community Mental Health Programs

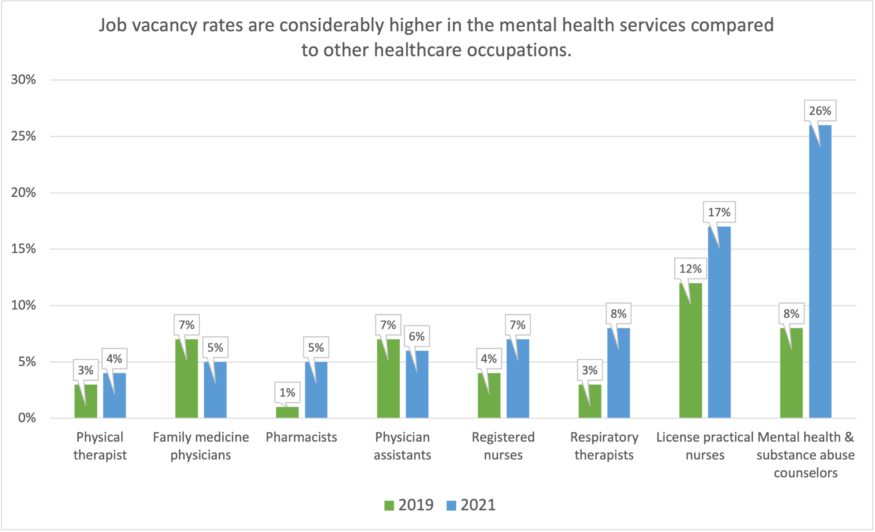

Figure 4. The vacancy rates for mental health providers is one of the highest in healthcare. MN Department of Health.[32]

How have rural organizations been successful in recruiting providers to their clinics? The most common method has been to offer clinical internships. These internships are required for graduation, but they also provide an opportunity for both the clinic and the soon-to-be-graduate to get to know one another. Interviewees reported that providing internship opportunities was more effective than any other recruiting strategy, making it much easier to hire their interns upon graduation.

“We do everything we can to make our interns feel like they are part of our team,” said Florest. “The best strategy in getting new professionals to our clinic is to bring them on as students. Without interns, I don’t know who we’d hire.”

Bringing in interns, however, presents its own set of challenges.

“Interns require a significant time investment from the organization,” said Karen Dolan, therapist and owner of The Journey Center in Marshall, MN, including time the supervising professional spends with the student instead of clients. It’s a big ask considering the waiting lists for services at most facilities. “How can we take time away from clients who need to be seen and give it to students?” said Dolan. Beyond the time, interns pose a direct cost to the clinic. Clinicians are reimbursed (paid) by the insurance company, Medicaid, Medicare, or another payer for their time spent seeing clients, but not so when they are supervising interns.

“I’d love to have interns,” Dolan said, “but [I’m] not sure how I can help my clients, pay the bills, and give the intern a good experience.”

The workforce challenge only intensifies around how to retain those who have already been recruited.

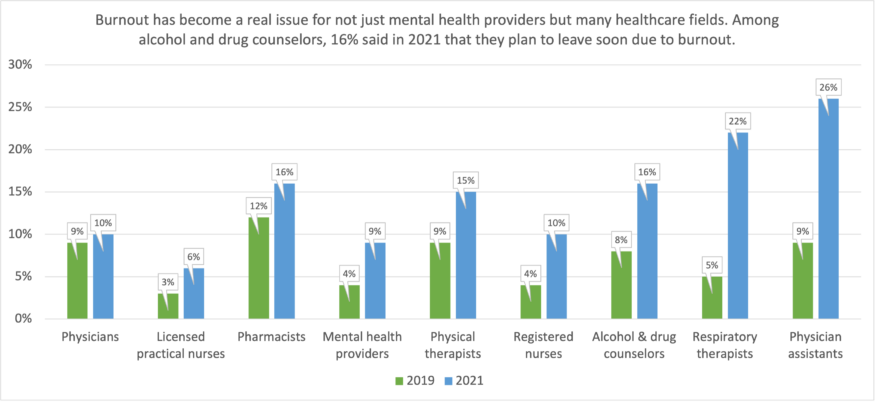

According to those interviewed, one of the leading causes of professionals leaving rural clinics is burnout, which negatively impacts not just the provider but also the quality of care for the client. A 2022 Minnesota Department of Health report on the healthcare workforce cited an increase in burnout among mental health professionals as a key factor in the workforce shortage both now and into the future.[33]

Figure 5. Burnout is a serious issue in most healthcare fields, not just mental health. MN Department of Health.

Addressing burnout among mental health clinicians will require a multifaceted approach,[34] but when our stakeholders were asked, most indicated that better pay would be a major help—that the financial compensation for mental health services right now is not in line with the level of education required to provide it.

Florest, in Virginia, MN, has seen people “abandon their clinical licensure, a license that took eight years to earn, leave it, and take a non-clinical job where they get paid more.”

According to Emerson in Grand Rapids, “Unless there is more reimbursement for these services, we will continue to see a downward trend in people leaving the field.”

Beyond reimbursement rates, other notable challenges to retaining mental health providers are the administrative aspects associated with providing care.

“Therapists are spending more and more time on administrative tasks, and less and less time providing therapy. This administrative burden continues to push professionals out of practice,” said Jin Lee Palen, executive director of the Minnesota Association of Community Mental Health Programs.

How the federal government and insurance companies set reimbursements is a complex process that even seasoned providers and billing specialists struggle to interpret. However, one thing was clear in our interviews: the cost of providing care is outpacing reimbursement rates. Expenses include the cost of obtaining the degree, obtaining clinical licensure, maintaining clinical licensure, administrative and billing overhead, and rent for the physical location where care is provided. A concerning trend, in fact, is the growing number of clinicians who have stopped accepting reimbursement and only see clients who can pay cash for services. In the current shortage, this trend makes it all the more difficult for those who rely on medical assistance to find a provider who will see them.

“I’m having to see more and more clients to keep up with the costs of providing care, which leads to more feelings of burnout,” said Tammy Ulmen, a therapist and owner of Stepping Stones Mental Health Center in Madelia, MN.

Impact on those who need care

“I’m full. I’m constantly full and have been for over the past year. People call on a daily basis trying to find help, and I have to say no. It’s a tough spot, being one of the only professionals in the community and having to turn away people who you know need help.”

—Karen Dolan, Therapist and Owner, The Journey Center, Marshall, MN

The lack of providers and available resources has a tremendous impact on serving the needs of rural communities. Without enough professionals to serve them, people with mental health concerns face waiting significant lengths of time or forgoing care altogether.[35]

Andrew Larson, the clinical director and owner of NorthStar Counseling Center in Hutchinson, sees this firsthand.

“We have a specialist in our clinic who provides a very specific type of care and who can have a waitlist for up to a year for services,” Larson stated in his interview. “This isn’t a psychiatrist who prescribes medication; this is a mental health therapist.”

“If I retired today, most of my patients would have nowhere to go. They simply wouldn’t get mental health care,” said Ulmen in Madelia.

“Often these rural clinics are the only options for Minnesotans to access mental health care. They are both the first line of defense and the safety net for these communities,” said Palen.

Basic needs: Can we graduate more counselors?

The issues facing mental health providers don’t start at graduation, however. Challenges in the education system that produces licensed clinicians are also compounding the shortage. We contacted 28 college programs that offer master’s-level programming leading to licensure in three fields, all common and important in mental health counseling: Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker (LICSW); Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor (LPCC); and Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT). The fifteen programs that responded represent a range of program delivery methods: traditional on-campus classes, online-only programs, and hybrid models. Six programs identified themselves as being in the Twin Cities seven-county metro area, while eight indicated they are outside the Twin Cities metro, and two stated they were unsure. (Respondents could choose more than one option, accounting for the additional response.) Of the respondents in Greater Minnesota who identified which county they were located in, they indicated their counties are either rural or serving adjacent counties that are rural.

We asked these fifteen programs: “From your perspective, what would need to happen to produce more licensed mental health professionals in Minnesota?” Three themes emerged from their answers.

Not enough faculty

When considering how to increase the number of licensed mental healthcare workers, the easy answer might be to just grow the educational programs, but two thirds of the respondents indicated their programs were limited in their ability to grow.

The average number of graduates the programs produce each year varied from 0-5 graduates to over 100. (Note: The programs reporting the highest average annual number of graduates were online programs, which are less restricted by geography (they reported pulling in students from all over the country, not just in Minnesota) and, in some cases, accreditation.)

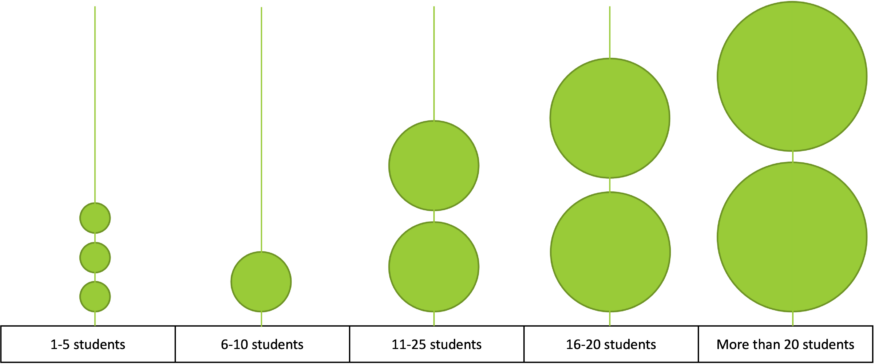

Ten of the fifteen respondents said that they turn students away each year because of capacity limitations, while the remaining five respondents noted that they did not have capacity limitations. When asked “Approximately how many qualified applicants does your program not admit per year due to capacity limitations?,” four respondents reported turning away 10 or more qualified applicants annually, while two more said they each turned away more than 20 students every year (Figure 6). (The remaining four programs didn’t provide specifics.) While these ten programs may not be representative of behavioral health programs in general, on their own, they indicated that combined, they are turning way at least 100 potential students every year.

Figure 6. The number of respondents in each category gives a rough estimate of how many students are turned away each year from programs leading to a licensed mental health career. Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University, Mankato.

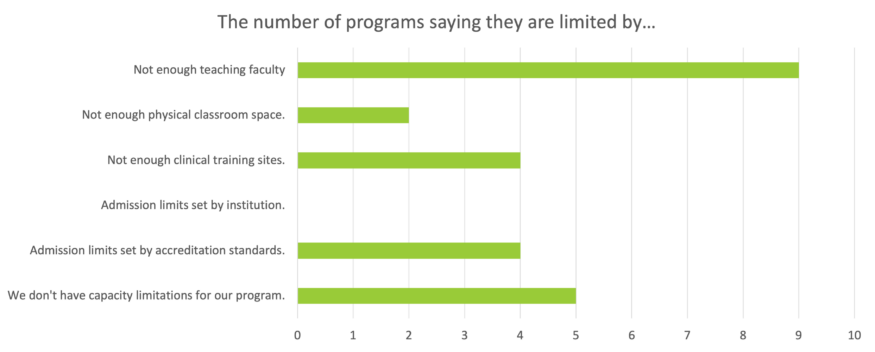

Figure 7. “If your program has capacity limitations, what is/are the reason(s)?” Nine of the fifteen respondents said they turn away prospective students due to a lack of teaching faculty, while another four said not enough clinical training sites and/or admissions limits set by accreditation standards. Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Why, when there is such a shortage of mental healthcare professionals, are higher ed programs turning away qualified students?

Graduating more professionals is not as simple as stuffing the classrooms with more students. Nine of the fifteen respondents noted a need for more faculty. As one survey respondent commented, producing more licensed mental health professionals would require graduating more students, “which means more faculty, which means more institutional support.”

Accreditation agencies, the organizations that accredit higher education behavioral health programs, also play a role, however. These organizations set standards for educational quality, including the design and content of the program, the number of credit hours required, and strict student-to-faculty ratios the school must abide by to maintain its accreditation. Unaccredited schools can still graduate students in mental health fields, but to become licensed (in Minnesota at least), those students will need to go through another layer of scrutiny to prove they are ready to become independently licensed, a step unnecessary for students graduating from accredited schools.

Accreditation ratios tie the number of students a program can admit each year directly to the number of faculty that program has.[36] For example, an LPCC program must maintain a 12:1 student-to-faculty ratio, basically 12 students to 1 faculty adviser. That means the number of students in the program cannot exceed the number of faculty x 12. To expand their programs, institutions would need either the accreditation standards to change or more funding to hire more faculty to expand while maintaining the ratios.

More financial support for students

In this category, two areas became apparent: a need to assist students with the cost of obtaining a master’s degree and the need for paid internships, something that is uncommon among master’s level mental health programs.

The cost of obtaining a master’s degree is challenging. A respondent from one of the educational programs pointed out: “Students are reluctant to become a mental health professional when they can make more money doing other things that don’t require a master’s degree.” Completing the work needed to become a licensed mental health professional typically entails not only the cost of obtaining the master’s degree, but also the cost of supporting themselves during their years in school and during the required practicum and internship, both of which are usually unpaid. In Minnesota, tuition alone ranges from $25,000 to $50,000, depending on the specific discipline and institution, for a master’s degree leading to clinical licensure.

Several survey respondents noted the importance of offering students at least a stipend during their practicum and internship experiences. Accreditation standards require students to complete both a practicum (100 hours of supervised experience that includes 40 client contact hours) and an internship (600 hours of supervised training, including 340 client contact hours). During their internship especially, students are also usually carrying coursework for at least three classes.

One survey respondent noted that the 700 hours of practicum and internship experience equates to approximately 20 hours per week during the academic year. In many other professions, particularly in STEM fields, a stipend or hourly wage is deemed appropriate, even at the undergraduate level.

Paying students for their work during internships is problematic, however. Just as the supervising clinician is often not paid for their time spent supervising a student, students or the clinic they are working at cannot always bill for the students’ time, even if they are providing services to clients. As such, it has been standard practice among mental health facilities to not pay students during their internships or practicums simply because they cannot afford to pay them.

Pay parity with other health professionals

Not only is funding their education, working (without pay) to complete a practicum and internship, and financially supporting themselves a daunting proposition, but pay is not on par with other healthcare professions, survey respondents said, echoing the national counseling organizations,[37] which state that a pay inequity exists among master’s level-trained healthcare professionals. As one respondent stated: “We also need better reimbursement in the field, as students are reluctant to become a mental health professional when they can make more money doing other things that don’t require a master’s degree.”

For example, master’s-level nurse practitioners receive a similar amount of training compared to licensed master’s-level behavioral health professionals, but a nurse practitioner’s average salary, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Outlook Handbook, is $120,680, compared to a licensed marriage and family therapist’s average salary of $49,880.[38] The nurse practitioner’s master’s degree takes approximately two years, while mental health master’s programs generally take two to three years. A typical nurse practitioner program requires fewer than 50 credits and approximately 600 internship hours compared to the master’s in marriage and family therapy or clinical mental health counseling that requires 60 credits and 700 internship hours.

The skill sets used in each field quite different, of course, but the reality is that both provide valuable health services, and the striking salary difference between the two, along with the cost of obtaining a degree, can be discouraging to those who would like to pursue a career in mental health counseling.

Policy recommendations

The growing amount of attention focused on mental health in the past few years begs the question: What happens when we talk about the importance of acknowledging mental health issues and encourage those who need help to get it, we but don’t then address the treatment gaps in our communities?

“People become disenfranchised,” says Katie Rubesh, mental health supervisor at North Homes Children and Family Services in Grand Rapids. “We talk all day about how important mental health is, but then why can’t people get the services they need?” The persistent rise in the rural suicide rate is a clear signal that rural individuals aren’t getting the mental health services they need. And given the growing populations of color, refugees, and non-English speakers in rural areas, the shortage of clinicians becomes even more acute.

How do we get more people into the mental healthcare workforce? How do we get more rural people to enter the field? Psychotherapy, the most common intervention for mental health challenges, requires that the provider understand the culture and way of life of the patient. Rural people want to talk to rural people who understand them. It is difficult for a therapist in Edina to understand the challenges of owning a dairy farm in Pipestone. At the same time, it’s important to note that urban areas don’t have an abundance of providers either. That therapist in Edina who could provide care to rural Minnesota probably already has a waiting list of clients locally.

We asked our respondents to identify potential solutions to the shortage. Their comments coalesced into these recommendations.

Upfront tuition aid

Tuition waivers, scholarships, and grants that support students at the beginning of the educational process.

The most agreed-upon strategy for increasing the workforce in general and rural specifically was that of some type of upfront tuition aid through some form of grants, scholarships, tuition waivers, etc. This type of upfront aid is not at all unusual in graduate programs, especially in the tech, science, and healthcare fields.

When considering how to get more people into a particular field, it’s crucial to consider how current policies could be affecting the pipeline from beginning to end. Probably the most significant consideration with the mental healthcare field is the sheer amount of financial commitment and resources a person needs to get from admission to not just graduation but licensure.

The state currently offers student loan repayment for mental health professionals who commit to serving underserved areas, but the program requires individuals to wait until they are independently licensed to qualify for the funds. The difficulty with this arrangement is that for nearly all mental health professional licensures there is a period of time after graduation—often two years or more—during which the clinician must work under a supervisor. During this supervised practice, clinicians find themselves in a financially precarious position. They have graduated, so their student loans are now in repayment status, but because they aren’t independently licensed yet, they aren’t eligible for the loan repayment program. At the same time, their pay is considerably lower than licensed clinicians even though they are providing the same services. These factors essentially make an education in mental healthcare a marathon where only the most financially fit on the front end can survive to receive their reward of student loan forgiveness at the finish line.

“Paying for school on the front end like a scholarship would increase our application pool 3,000%. … It’s worked in other states I’ve worked in, so we should do it here,” says Schlenske, referring to Washington State, where this type of financial aid is being offered.

Providing financial aid on the front end “would make a huge difference in people deciding on their career path,” says Rubesh. “People know you’re not going to make a lot of money in mental health, but if they knew their graduate education would be paid for, it would help get them into the field.”

The model of paying for the training of needed healthcare professionals is not new. Minnesota recently launched the Next Generation Nursing Assistant initiative to grow the Certified Nursing Assistant workforce. The state of Ohio invested $85 million dollars to meet the growing demand for licensed mental health providers there.[39] Among the programs funded was one that provided scholarships for students pursuing mental health degrees and another that invested in clinical internship placements.

More support for educational programs

Limits make some colleges and universities turn students away

If Minnesota aims to increase the number of students entering graduate-level mental health programs, it will also be important to understand those programs’ training capacities and what limits their ability to take on more students. As discussed earlier, many training programs are limited by accreditation rules—namely student-to-faculty ratios—that cap the number of students a program can take largely because the school can’t afford to hire more faculty. Trying to help the situation by changing the accreditation rules is not necessarily desirable: the rules were created to ensure quality training for these students who plan to work with our most vulnerable populations. However, more funding to colleges and universities would help them increase their faculty numbers, allowing them to take on more students and increase facility space if necessary.

Grow internships in rural places

Students are more likely to stay and practice near where they interned

Research has shown[40] that students tend to stay where they were trained. Rather than trying to lure graduates away from the urban communities where they interned, increasing the number of sites for clinical internships in Greater Minnesota would help in recruiting students to stay in and serve these underserved communities. As discussed earlier, however, financial assistance is needed to help offset the costs clinics take on when training new clinicians.

“My clinic would absolutely consider taking on clinical interns if there was compensation for the lost service time to provide the needed oversight and supervision,” said Dolan.

Early introduction to the mental healthcare field, especially for rural kids

High school and middle school is not too early

Research[41] indicates that the best way to build a rural mental health workforce—or any rural workforce—is to grow it locally, as this CRPD report explains. To get students interested in mental health careers, they need to be introduced to the profession as early as high school or even middle school. The Center for Rural Behavioral Health at Minnesota State University, Mankato, recently started the Behavioral Health Career Exploration Program, which goes into high schools around the state to discuss careers in mental healthcare. The goal is to encourage students to pursue the field with the hope that they will return to their home community or another rural community to provide services after training.

Pay parity

Reimbursement rates are a federal issue, but the low pay disincentivizes students

Pay in any part of healthcare is based on the reimbursement rate, that is the rate that Medicaid/Medicare will pay for the provider’s time; private-pay insurers often use this federal rate as a guideline when negotiating contracts with clinics. Dealing with federal reimbursement rates is largely beyond the scope of a state legislature, but it is still important to understand that the low pay for many mental health careers is an issue and is influencing students’ career decisions in ways that work against rural communities and low-income communities.

A national Counseling Compact

It’s a step forward, but not a magic bullet

At the start of COVID-19, we quickly learned the value of tele-healthcare. Mental health challenges not only didn’t stop during the pandemic, they increased,[42] and therefore, the limitations on in-person meetings forced providers to adopt telehealth even though it was still a mostly unknown avenue of treatment. Nearly three years later, telehealth has become an indispensable treatment option, helping providers reach clients who may not otherwise be served.

To help with the mental healthcare workforce shortage, states have come together to create the Counseling Compact (counselingcompact.org), an agreement that would allow providers licensed in member states to serve clients in other member states where they may not be licensed. This national effort is a huge step toward increasing capacity across the country, but it’s important to remain aware that this is not a fix-all solution. Rural Minnesota residents may be reluctant to see a provider from a big city in another state. And while the Counseling Compact may open up more access to mental health providers, it also has the potential to drain from the area those mental health providers who choose to see a broad range of clients from across the nation to the exclusion of local clients. This is especially a risk for clinicians connected to for-profit providers. The way in which the compact could expand the pool of potential clients, it will be tempting for providers to cherry-pick only private-pay clients, leaving out people in both rural and urban communities who depend on Medicaid and other options for low-income individuals.

Given all the barriers to care for mental health clients in rural communities, the mental health practitioners who serve them find themselves advocating for their clients in the community itself, to overcome the stigma associated with mental health and the practical barriers to receiving clinical mental health services. As the need and demand for mental health services grow, the lack of services in rural areas only becomes more obvious. Anything that helps close this gap, whether it is financial assistance for students, for rural clinics to provide more training opportunities, or for colleges and universities to help them accept more students, can only improve the landscape for mental health services in rural Minnesota.

Established in 2022, the Center for Rural Behavioral Health at Minnesota State University, Mankato, has the mission of improving access to behavioral healthcare for residents of Greater Minnesota, including recognized reservations. Along with our community partners and through research, workforce development, and customized training, the Center for Rural Behavioral Health’s goal is to grow the behavioral health workforce so that every Minnesotan, regardless of zip code, can get mental healthcare when they need it.

To learn more about the Center for Rural Behavioral Health, visit their website:

https://ahn.mnsu.edu/services-and-centers/center-for-rural-behavioral-health/

Appendix

A total of seven interviews took place in the fall of 2022. A big thank you to those who participated:

- Karen Dolan, Therapist and Owner, The Journey Center, Marshall MN

- Hillary Emerson, Director of Human Resources, Northern Homes Children and Family Services

- Annmarie Florest, CEO, Range Mental Health, Virginia MN

- Andrew Larson, Clinical Director and Owner, NorthStar Counseling Center, Hutchinson MN

- Grand Rapids MN

- Jin Lee Palen, Executive Director, Minnesota Association of Community Mental Health Programs, St. Paul, MN

- Katie Rubesh, Mental Health Supervisor, North Homes Children and Family Services in Grand Rapids MN

- Jon Schlenske, CEO, Southern Minnesota Behavioral Health, New Ulm MN

- Tammy Ulmen, Therapist and Owner, Stepping Stones Counseling, Madelia MN

Additional references

Catron, T., & Weiss, B. (1994). The Vanderbilt school-based counseling program: An interagency primary care model of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2(4), 247–253.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Suicide in Rural America.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). About Rural Health.

Heitkamp, T., Nielsen, S., & Schroeder, S. (2019). Promoting Positive Mental Health in Rural Schools. Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network.

Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving Mental Health Access for Low-Income Children and Families in the Primary Care Setting. Pediatrics, 139 (1).

Lee, S. W., Lohmeier, J. H., Niilesksela, C. & Oeth, J. (2009). Rural schools’ mental health needs: Educators’ perceptions of mental health needs and services in rural schools. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 33(1), 26-31.

Minnesota State Demographic Center (2017). Greater Minnesota: Refined & Revisited.

Minnesota State Demographic Center (2020). Long-term Population Projections for Minnesota.

Minnesota Department of Health (2021a). Minnesota Suicide Mortality, Preliminary 2020 Report.

Minnesota Department of Health (2021b). Rural Health Care in Minnesota: Data Highlights.

National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. (2017). Understanding the Impact of Suicide in Rural America: Policy Brief and Recommendations.

National Alliance on Mental Illness Minnesota. (2021). Suicide Prevention.

Slama, K. (2004). “Rural culture is a diversity issue.” Minnesota Psychologist, 9-11.

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Urban and Rural.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2018). Rural Poverty and Well-being.

Endnotes

[1] Minnesota State Demographic Center, Long-term Population Projections for Minnesota, 2020.

[2] United States Census Bureau, Urban and Rural, 2020.

[3] RUCA codes originate with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Both the Minnesota Department of Health and the Center for Rural Policy and Development use RUCA codes in analysis but group the codes in slightly different ways, achieving basically the same results, a representation of the relative “rurality” of a location.

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About Rural Health, 2017.

[5] National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, Understanding the Impact of Suicide in Rural America: Policy Brief and Recommendations, 2017.

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Wonder data portal.

[7] Minnesota Department of Education, Minnesota Student Survey, 2022.

[8] Cran, Tom, and Megan Burks. “Report: Greater Minn. Suicides Were Majority of Gun Deaths in 2021.” News. MPR News, September 16, 2022.

[9] National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, Understanding the Impact of Suicide in Rural America: Policy Brief and Recommendations, 2017.

[10] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rural Poverty and Well-being, 2018.

[11] Minnesota Department of Health, “Poverty: Median Household Income.”

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, Minnesota.

[13] Center for Rural Policy & Development, Rural Minnesota Atlas, “Median Household Incomes, 2021.”

[14] Minnesota Department of Health, Minnesota Suicide Mortality, Preliminary 2020 Report, 2021a.

[15] Minnesota Department of Health, 2021a.

[16] Catron, T., & Weiss, B., The Vanderbilt school-based counseling program: An interagency primary care model of mental health services, Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2(4), 247–253, 1994.

[17] Minnesota Department of Health.

[18] Minnesota Department of Health, 2021a.

[19] Of the 30,510 licensed mental health workers in Minnesota in December 2022, 22% couldn’t be assigned to a location. Reasons include not reporting an address to their licensing board, living out of state, and not actively practicing at the time. The percentages shown here indicate the approximately 24,000 workers who could be assigned a location.

[20] Minnesota Department of Health, 2021a.

[21] Minnesota Department of Health, Rural Healthcare in Minnesota: Data Highlights, 2022.

[22] National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, 2017.

[23] Hodgkinson, Godoy, Beers, and Lewin, 2017, Improving Mental Health Access for Low-Income Children and Families in the Primary Care Setting. Pediatrics, 139 (1).

[24] Lee, S. W., Lohmeier, J. H., Niilesksela, C. & Oeth, J. (2009). Rural schools’ mental health needs: Educators’ perceptions of mental health needs and services in rural schools. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 33(1), 26-31, & Slama, K. (2004). Rural culture is a diversity issue. Minnesota Psychologist, 9-11.

[25] National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, 2017

[26] Slama, 2004.

[27] Minnesota Department of Health, 2021a.

[28] Minnesota Department of Health, Rural Health Care in Minnesota: Data Highlights, 2021b.

[29] Minnesota State Demographic Center, 2020.

[30] Mackie, M. S. W., & Force-Emery, P. (2012). Social work in a very rural place: A study of practitioners in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Contemporary Rural Social Work Journal, 4(1), 6.

[31] Mackie, P. F.-E., & Lips, R. A. (2010). Is There Really a Problem with Hiring Rural Social Service Staff? An Exploratory Study among Social Service Supervisors in Rural Minnesota. Families in Society, 91(4), 433–439.

[32] Minnesota Department of Health, “Minnesota’s Healthcare Workforce: Pandemic-Provoked Workforce Exits, Burnout, and Shortages,” 2022.

[33] Minnesota Department of Health, “Minnesota’s Healthcare Workforce: Pandemic-Provoked Workforce Exits, Burnout, and Shortages,” 2022.

[34] “Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce,” 2022.

[35] National Council for Mental Wellbeing, “Study Reveals Lack of Access as Root Cause for Mental Health Crisis in America”, 2018.

[36] Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2016 CACREP Standards, 2015.

[37] Lee, Derek J., “It’s time for a financial change in counseling,” Counseling Today, American Counseling Association, June 23, 2022.

[38] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2021.

[39] Gov.ohio.gov, “Governor DeWine announces proposal for $85M investment to grow Ohio behavioral healthcare workforce,” 2022.

[40] Mackie, P. F.-E., & Lips, R. A., 2010.

[41] Mackie, M. S. W., & Force-Emery, P., 2012.

[42] World Health Organization, “COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide,” 2022.