By Whitney Oachs, Elizabeth Gehlen, Josiah Moore & Ryan Redmer

Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs graduate students

For our full report including results, methodology, bibliography, and glossary of terms, download this PDF.

While there has been a lot of talk about diversity in the last year, not much is known about BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) groups in rural Minnesota, even though demographic data suggest a significant increase in immigrant and refugee populations centered in meatpacking towns around the state.

This spring, my classmates and I at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs completed a capstone thesis project investigating outreach and inclusion efforts among rural Minnesota government officials and community leaders. In partnership with CPRD, the Minnesota Council on Latino Affairs, the Council for Minnesotans of African Heritage, and the Council for Asian-Pacific Minnesotans, we focused our research on four rural Minnesota communities with a documented increase in immigrant and refugee populations.

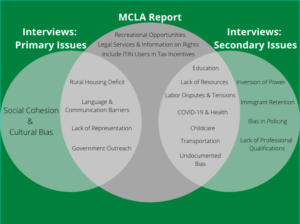

Earlier in the pandemic, the MN Council on Latino Affairs (MCLA) conducted a qualitative survey on Latino perspectives in 2020 titled “Latino Minnesotans in the Time of COVID-19.” The study was completed through community listening sessions with Latinos living in Greater Minnesota and found that translation services, education, healthcare, social services, taxes, and housing access were among the most pressing issues affecting rural Latinos. There are literally hundreds of ethnicities and languages represented in Greater Minnesota, and the MCLA report provides important insights into the needs and concerns of rural immigrant, refugee and BIPOC communities. Despite differences across ethnicities and identities, the experience of Latino Minnesotans provides an important proxy for investigating immigrant and refugee needs more broadly.

Given this literature describing community concerns, our capstone research team decided to investigate the local government side of diversity and inclusion outreach. We could then compare these findings with MCLA’s survey results.

Our research would involve speaking with twenty government officials and community leaders in four cities across rural Minnesota:

- City of Austin (Mower County)

- City of Pelican Rapids (Otter Tail County)

- City of Willmar (Kandiyohi County)

- City of Worthington (Nobles County)

We chose these cities because all four reported notable increases in foreign-born residents in the last twenty years (Figure 1), they are all located within rural counties, and they are home to major meatpacking employers that serve as both the economic driver of each city and the largest employer for immigrants and refugees.

Figure 1. Three of Four Cities Reported Doubling their Foreign-Born Population, 2000-2019

Interviewees included city council members, school officials, county administrators, city mayors, and police chiefs. All our hour-long interviews took place over Zoom. Table 1 includes some of the questions we asked.

Table 1: Interview Questions as They Relate to Research Questions

|

Research Questions |

Related Questions for Interviewees |

|

1. What do local government officials and community partners identify as the most pressing issues facing their local immigrant and refugee populations? |

|

|

2. What strengths and challenges do local government officials and community partners cite within their primary outreach and inclusion efforts? |

|

Why this research is important

Because rural Minnesota’s population has been predominantly white for decades, newfound racial and ethnic diversity has caused issues related to community cohesion, racism, and public services. However, immigrant workers provide an important service to Greater Minnesota’s economy. BIPOC workers not only make up the majority of employees on most meatpacking floors, but their families are responsible for sustaining rural population density. While population declines are widespread among rural communities, counties with a high ratio of immigrant and refugee in-migration have actually grown.

This increase in diverse in-migration has led to challenges for local government officials and new residents alike. With old-fashioned ideas about culture and language still prevalent in small towns and cultural differences breeding disconnect, it is more important than ever for local governments to foster understanding and community sustainability. In small cities, all residents rely on one another whether they want to or not, but add in cultural differences, language and translation issues, and even the simplest communications are further complicated.

In our study, we found that successful community cohesion is fostered especially among young people and families in local schools, worker relationships on the meatpacking floor, and the establishment of ethnic restaurants across all cities. Issues and challenges included problems that are both unique to immigrants and refugees—like language translation and social service connections—and problems that affect all types of rural residents—like housing and access to higher education.

Findings and Analysis

We were able to split the findings from our interviews into five main categories:

- Social cohesion and cultural bias

- Government outreach attitudes and barriers

- Language and communication

- Representation in government

- Rural housing deficit

Social cohesion and cultural bias

In our conversations with local officials, we found that white residents’ perceptions of local immigrant and refugee groups were especially affected by how recently that immigrant group had arrived coupled with racial/ethnic bias, but multiple interviewees also cited that attitudes toward immigrant and refugee groups have shifted in a positive direction over time. In three of the four cities we studied, Latino groups were the first to migrate to those communities and have therefore “better assimilated” into the surrounding culture. Interviewees cited newer groups, such as Somali and Karen, have had a “harder time” getting involved and integrated into each town. Though most government workers and community leaders recognize this difference is due to the time of arrival, some perceived the difficulty as a “lack of interest” in community involvement among different racial and ethnic groups.

Government outreach attitudes and barriers

While some government officials saw specific outreach to immigrant and refugee communities a necessity, others opposed the notion that any one group should receive “special treatment.” One official in Austin made it clear that specific outreach to immigrant and refugee groups is an important element of government purview, which is reflected in the city’s welcome center and honorary city council seat. In comparison, an official in Worthington stated that it was up to the various immigrant communities to express their needs to local leaders:

“If you don’t tell us what the shortcomings are, we won’t know that there are shortcomings. So, I’m not shy about putting the responsibility back on other individuals that they need to step up and work with us.”

Language and communication

Language and translation were by far the most frequent issue cited in interviews. Because it is expensive to translate government documents, all four cities face barriers in effective communication with populations speaking English as a second language. Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the necessity for translation and/or improved communication only increased. In order to distribute materials in readable languages, cities either allocated additional resources to translation or partnered with local meatpacking employers who have translators on staff. The problem with increasing resources put toward translation is the myriad spoken languages present in each town. For many Latinos even, Spanish is the second language after their native/Indigenous tongue. As such, it is impossible for any city to translate and disseminate documents in every language or to the correct groups.

Representation in government

Although representation within the government remains a challenge for rural communities everywhere, some communities have adopted intentional systems for fostering diverse input into government decisions. The officials brought up three perceived barriers to representation in government (whether for elected or staff positions) for immigrant and refugee groups:

- Lack of community interest, which was found among both BIPOC and white residents. Officials cited a gap in immigrant and refugee community interest in government involvement, as well as the needed collaborative action required by local governments to effectively provide for these communities.

- A skills mismatch leading to a lack of diversity in employment. Discrepancies between worker qualifications and traditional hiring requirements make it difficult for local governments to consider BIPOC individuals for public positions.

- Overburdened BIPOC community leaders. Finally, individual community leaders who are involved in government decisions quickly become overtaxed when stuck representing their entire demographic, despite being just one person.

Rural housing deficit

Greater Minnesota has a well-documented housing deficit, due largely to the inability for municipalities to attract developers. With the cost of materials skyrocketing, and the profit-margin for building much lower in rural areas, cities are struggling to provide not just traditional housing, but housing that meets the different needs of the immigrant and refugee communities. As one Austin City Councilmember succinctly stated:

“Housing is the biggest challenge for refugees. It is easier for someone who has been in America longer to get a house or to get an apartment compared to a refugee who just moved here… [M]ost immigrants who moved to Austin have multi-generation families. You know, they have a family of more than four and more than five. So with housing or apartments built in Austin before they had all those refugees and immigrants, it’s all one or two bedrooms or a small house.”

Comparing interviews and literature

Our findings show that local government officials are aware of many of the main issues identified by local BIPOC communities in MCLA’s earlier survey (Figure 2). Nevertheless, our interviewees noted feeling “at a loss” over how to amend such issues with the limited resources available in rural municipalities and counties.

Moving Forward

Rural immigrants and refugees are assets to the communities they live in. These residents provide population density, fill employment gaps, and infuse their new homes with their culture, cuisine, and young people. Without immigrants and refugees, Austin, Pelican Rapids, Willmar, and Worthington would all likely report the same kind of population and economic decline present in smaller cities that have not experienced in-migration.

What our conversations found, though, was that the most successful instances of community cohesion and outreach exist in areas where resources, public-private partnerships, and community voices are all successfully integrated. From Austin’s honorary city council seat, to the welcome centers which connect new migrants with social and translation services, there are many instances of promising policies which serve to promote equity, inclusion and togetherness.

Nevertheless, the problems associated with adapting to a new and growing community is not painless, and disagreements on the best path forward exist among even the most well-intentioned community leaders. This report focused on outreach and inclusion efforts on the part of government officials, but there is still room for further research on the strengths and challenges identified in the interviews. Some of those questions for further research include:

- What can rural cities do to maximize partnerships with local organizations?

- What targeted investments can be made in smaller Minnesota communities to expand their capacity to perform immigrant and refugee inclusion work?

- How can the state government invest in immigrant and refugee inclusion in smaller communities where private-sector investment capacity is less robust?

- How can a commission build the capacity and consensus necessary to create a strategic plan for inclusion that a city council will carry out?

- How can inclusivity-focused commissions communicate with one another and learn from the strategies employed in other Greater Minnesota cities?

- How can smaller communities develop formal partnerships with clearly defined roles in order to better serve their immigrant and refugee communities?

- Do JBS, Hormel, Jennie-O, and West Central Turkeys have the capacity to ramp up their investments in providing services for their workforce and the greater immigrant and refugee community?

The task of thinking through immigration’s impact on the social fabric of Greater Minnesota and fully addressing the community needs that arise from these changes is a complicated yet pressing issue. Local governments have the ability to build community through embracing difference, though this can only occur through significant government investment and community collaboration. While the sample cities discussed in this report have all worked to make immigrants and refugees feel welcome, there is more that can and should be done in communities across rural Minnesota.

For our full report including results, methodology, bibliography, and glossary of terms, download this PDF.