For most parts of the state, the coming workforce squeeze is already here. A smaller pool of workers means businesses—and communities—will be competing for their attention. Communities around Minnesota are starting to work on how to make their towns the places people want to move to. But part of making a community a great place to live involves not just cosmetic improvements but also deep infrastructure upgrades as well: updated broadband, water and sewer, expanded public transit, and more accessible health care.

The coming workforce squeeze

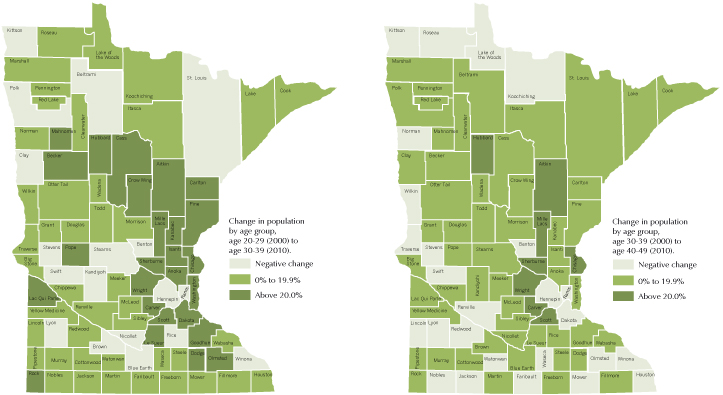

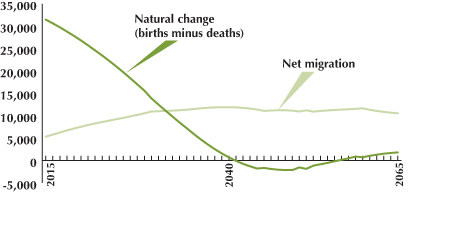

Population projections predict that as Baby Boomers retire, there will not be enough workers to fill the vacant jobs. As we discussed in our earlier brief, “The Coming Workforce Squeeze,” in Minnesota the number of Baby Boomers becoming seniors is expected to double over the next twenty years as an additional 784,000 cross the 65-year mark. In the same time period, our working-age population (16-64) is projected to shrink by about 5%, or 170,000 people.

A shortage of workers is nothing new for many rural communities, but problem is now spreading to larger population centers. The Twin Cities area is expected to lose workforce-age population at the same rate as the rest of the state, just a few years later. And it’s not just in Minnesota.

So how does a rural community compete against big population centers? Cities around the state are working on just this question. They are finding that the key to attracting workers is understanding what motivates people to change where they live. Many people are looking for jobs, but many of today’s workers are also looking for a lifestyle that fits their personal quality-of-life checklist. People are mobile and they have options—they may be able to work remotely or plan to start their own business—and therefore they have much more latitude on where to live.

Who are today’s workers—and tomorrow’s?

The traditional pool is not so traditional anymore

Because of these changes in the demographic landscape—when there seemed to be an endless supply of young Baby Boomers to draw from—the worker pool promises to look rather different from what we’re used to. Here’s a quick list of some of the groups out there and what they’re looking for:

“It’s a nice place to raise a family”: For these workers, where they raise their children is more important than what job they get. They may be mid-career employees of large companies who would like to work remotely instead of commute, people who plan to start their own businesses, or immigrants from rural Africa or Mexico who are concerned about the safety of big cities. Their myriad reasons come down to one thing: they want a good environment for their kids.

Data: U.S. Census Bureau.

It’s an almost invisible phenomenon University of Minnesota Extension researcher Ben Winchester has dubbed the “brain gain,” as opposed to the term “brain drain,” which has been used to describe the depopulation of rural counties over the last several decades. By analyzing Census data, Winchester has found that people move around at different stages in their lives; not everyone moves to the Twin Cities and stays there. When Winchester interviewed nearly 100 newcomers to the west central region of the state in 2008, he found that these mid-career movers had chosen the region for good schools, natural beauty, and other quality-of-life reasons. Jobs didn’t even make the top ten.[1]

A recent Washington Post article told of a small town in Japan that, despite its stunningly beautiful rural location, was losing population until the community started working to attract young families “weary of big-city life.” Trading the long commute for more time with their kids was a big selling point for many who made the move.[2]

The key asset for this village was that it had good broadband service, allowing people to either work remotely for their current employers or run their own businesses, serving clients all over the country.

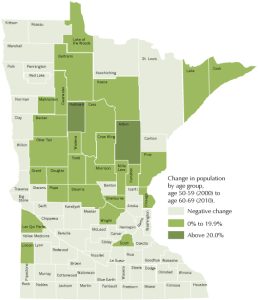

Seniors transitioning into retirement: An important source of workers will be those who are already employed. The trend nowadays for seniors is to plan a long glide into retirement that may involve downscaling their current job or leaving one job and picking up another one they can take with them past age 65. The plan may also include a move to where they want to retire while they’re still working. [Include 50-60 move map]

Data: U.S. Census Bureau.

Seniors looking for a place to retire will very likely be looking for a place with or near good health care. Employing older workers may also mean providing some accommodations for people with limitations in eyesight, hearing, or mobility. These could include anything from special equipment to reliable public transit for those who can work but would prefer not to drive.

Difficult to employ: The labor participation rate is the percentage of how many people of working age (16+) are active in the labor force. Minnesota’s labor participation rate tends to be on the high side, standing at a little over 70% during the summer of 2015. A good chunk of that remaining 30% is made up of senior citizens who have simply retired and people who for one reason or another have chosen not to work (stay-at-home moms, students). They are still counted as part of the potential labor force.[3]

The rest, though, are people who have a difficult time getting and holding jobs (persons with disabilities, low education, low English skills, a criminal record). Willing members of this group make up a potential pool of labor, but they will require some accommodations, such as flexible public transit and specialized training to prepare them for the job market.

Remote workers: One key change for employers, especially for those looking to fill high-skill positions, will be to hire people who will continue to live someplace else. Adequate, affordable broadband opens up opportunities for companies to hire workers with the skills they need without requiring the workers to move.

Minorities: More and more these days, the people looking for jobs in Minnesota weren’t born here, and if they were, they’re from an ethnic or racial group other than white. Racial and ethnic minorities are the only population groups growing right now in the U.S. The Minnesota State Demographic Center projects that the growth rate of the white population will decline, adding fewer people each decade, while the growth rate for minorities will stay steady.

Data source: MN State Demographic Center

But while minorities are a promising source of future workers, their graduation rates and employment rates still lag behind those of whites. Finding solutions to help minorities succeed will be a key part of keeping the state’s workforce active, vibrant, and successful.

Making a competitive community

What are the opportunities?

So how do rural communities compete as more demand is put on this future pool of workers? The key is to understand what makes people choose to live where they do.

Few Olympic athletes are good at everything. In fact, they’re usually specialized. One is best at sprinting, while another excels at heaving a shotput. Communities are the same way, or rather, they’re all different. Rather than trying to be all things to all people, a community should figure out what they do best, then get the word out to those interested in that lifestyle.

Millennials especially are placing an emphasis on location and lifestyle. The New York Times ran a group of articles discussing the top cities college grads are choosing to move to and why.[4] At the same time, the Minneapolis Star Tribune ran articles talking about how Minnesota was losing college grads to southern and western states.[5] In both cases, the narrative was about lifestyle and quality of life.

A person’s decision-making process may include the types of jobs available in the communities they’re considering, but they may also take into consideration what outdoor recreation is available, nice parks and good schools, educational opportunities for adults, and the quality of housing, according to a report by the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire.[6] The researchers found that they could divide communities in rural America into different categories depending on their strengths, economies, and history. Each category appealed to different people for different reasons.

Another New York Times article looked at a study that analyzed a federal program helping very low-income families move out of poverty-stricken neighborhoods to low-poverty communities. Families chose their new communities for safer neighborhoods and better schools—in other words, a better quality of life. The study found that while the parents’ income didn’t improve substantially after the move, the income of their children when they became adults tended to be considerably better than that of peers who stayed behind in the old neighborhood, and they tended to be healthier, too.[7]

What are assets?

Assets are what make a community a special place to live. In southwest Minnesota, Pioneer Public Television and the Southwest Minnesota Workforce Council have put together a video showcasing the small-town lifestyle and natural beauty of southwestern Minnesota. The video is on several web sites and is being shown at workforce centers in the Twin Cities to people who might be thinking about a smaller community as part of their job search.[8]

In a series of reports being written for the McKnight Foundation, author Jay Walljasper is looking at the opportunities and challenges for communities in Greater Minnesota. His first report focused on southeast Minnesota and found a number of communities working to reinvent themselves with a variety of exciting new activities and attitudes.[9]

These towns are not trying to recreate a mini urban experience or be all things to all people, but to identify what their community does well, then showcase it so that people who are interested in that lifestyle will check it out.

Neighboring towns need to work on these ideas together, too, says Extension’s Ben Winchester. He has found that people will seek out a region that offers the lifestyle they’re looking for, then check out several towns in that area before settling on one. And just because they settle in one town doesn’t mean they never leave it. They will work, play, and shop around the region. “They want to move to a place where they can enjoy the whole area,” Winchester says.

What are the challenges?

But while just about any community has assets it can put to good use, it probably also faces a number of challenges to bringing in new people. Our research revealed several factors that can pose a challenge to rural communities looking to be competitive. If they can be fixed, however, they can be definite selling points.

Broadband: Affordable broadband at useful speeds is crucial when it comes to attracting newcomers. Many who move to rural areas do so expecting to be able to work remotely or start their own businesses or even just stream Netflix at home. For people who are as used to having broadband as they are running water, it can make the difference in which community they choose.

In a bigger picture: “Broadband adoption in rural areas (assuming it is available and affordable) can help address three main disadvantages compared to metro areas: availability of skilled workforce, larger business markets, and investment capital. In other words, the density advantage of urban areas over rural areas can somewhat be mitigated using information technology,”[10] says Dr. Roberto Gallardo of the Mississippi State University Extension Service’s Intelligent Communities Institute. Broadband isn’t a silver bullet, Gallardo says, but it can help level the playing field between urban and rural.

Wages: There’s no way to sugar-coat it: wages in Greater Minnesota counties are lower than in the Twin Cities, in some places much lower. Simple supply and demand means that as workers become scarcer, employers may need to offer higher wages to tempt them, especially higher-skilled workers.

Housing: Housing for workers is in high demand and low supply in many rural communities and is a primary hurdle keeping businesses from bringing in the employees they need. Because the cost of building new housing can be largely unrelated to the local economy, builders are finding they can’t build new housing for a price that local residents can afford. At the same time, rural communities tend to have a high percentage of older housing stock. This housing is often owned by the elderly, whose health and income may prevent them from keeping their homes up to date. The result is a large percentage of housing in need of a considerable amount of work to make it sellable.[11]

While workforce housing was a major topic during the legislative session in 2015, the proposed fix was left in conference committee to be addressed in 2016.[12]

Roads, bridges, and transit: In Greater Minnesota, every regional center, whether large or small, is surrounded by vibrant and vital rural communities that interact with those major centers for their commerce and employment, said Jonathan Zierdt, executive director of Greater Mankato Growth, in a recent Rural Minnesota Radio interview.[13]

To move among these communities, people need reliable roads and bridges, but because of the changing demographics of the state, they are also increasingly in need of alternative forms of transportation. The swelling number of older Baby Boomers means a growing number of people either unwilling or unable to drive themselves around, especially in winter and especially for those who live farther away from health care or shopping. Immigrants and minorities have a lower car ownership rate, too, as do low-wage workers. This all adds up to a growing demand for public transit.

Right now there are only four counties in Minnesota that don’t have some type of public transit, but that doesn’t mean every resident in the other 83 counties has access to service. State and local governments are actively working to improve public transit in both urban and rural areas by expanding dial-a-ride and fixed-route services, but there are still challenges. People who work at night and people who need to get to a city in a neighboring county for work or healthcare or grocery shopping are two groups facing public transit challenges, according to the Minnesota Department of Transportation. The big challenge to planners is finding drivers and of course finding the funding.[14]

In a generational shift, young adults have become increasingly focused on biking and walking and are much less likely than their parents to own a car. Major transportation policy at the federal and state level is helping rural communities with their walkability and bikeability. When the city of Albert Lea made improvements to the downtown that encouraged pedestrian traffic, officials found that residents got out more, visited downtown more, and were in general healthier.[15]

Water systems: Water infrastructure is perhaps the most important and least visible piece of a community’s infrastructure. Water and wastewater infrastructure are carefully regulated by state and federal policies to protect the environment and people’s health, but that infrastructure is also expensive to maintain, and the smaller the town, the higher the cost per resident. When a system becomes overburdened, not only are residents’ health and the surrounding environment put at risk, but so is any chance for growth. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency keeps an inventory of wastewater infrastructure needs in Minnesota. The potential bill to bring everything in Greater Minnesota up to date is staggering.[16]

Working together: Most problems in a community can’t be solved by one sector or one group or one individual. By working together, local businesses, chambers, government, and nonprofits can figure out how to develop their community as a whole. For example: the Brainerd Lakes Area Economic Development Corporation, area businesses, local government, and nonprofits worked together over several years to create an entire campaign aimed at attracting high-tech workers and businesses.

Effective solutions might involve specialized education for local unemployed residents, housing that needs upgrading to modern standards, or even a branding and marketing campaign for the community, as the Fergus Falls and the Brainerd Lakes regions are doing. These are big issues that require communitywide thinking.

Cultivating dedicated workers with ongoing education: To get the right people with the right skills, companies are working on their own education programs. Ongoing education for current employees teaches interested and motivated employees the skills they need to advance on the job. For workers, training like this helps them feel like valued employees, reducing both turnover and the feeling of being trapped in a dead-end job.

It’s also important to not forget about people already in your community who may want a job, but for some reason are having a hard time finding and hanging onto one. These difficult-to-employ people may require specialized local training that takes into account the challenges they’re facing, whether it’s a disability, inadequate child care or an unreliable car.

Child care: Another very real obstacle to work for some families is child care, especially for people working nights, evenings or weekends. This is another area where employers can work with local government and nonprofits to figure out solutions.

“Welcome to our town”: One of the biggest challenges for rural towns may be to find ways to make newcomers feel welcome and feel like they are a part of the community. Small towns may not have a huge assortment of jobs, but they “can offer people a place where they’ll know their neighbors, to partake in the richness of community life and feel like they have opportunities,” said Walljasper on a recent Rural Minnesota Radio interview.[17] This feeling of belonging to “something bigger than themselves,” as Walljasper described it, is very likely the most important thing a community can offer new residents.

The new reality

The workforce shortage is well documented, and it’s here. Rural communities are already competing—and will have to compete harder—for workers now. The good news is that many people are looking for the type of assets rural communities have to offer, but there are also challenges that need to be addressed if communities are going to be able to truly succeed.

Works cited in this article:

[1] Winchester, Spanier, and Nash, “The Glass Half Full: A New View of Rural Minnesota,” Rural Minnesota Journal, 2011, https://www.ruralmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/RMJ6-11winchester.pdf

[2]Fifield, Anna, “Opting out of the daily grind,” Washington Post, May 26, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/with-rural-japan-shrinking-and-aging-a-small-town-seeks-to-stem-the-trend/2015/05/26/3dac3d90-fa8a-11e4-a47c-e56f4db884ed_story.html

[3] Belz, Adam, “Minnesota’s labor participation rate is falling, but let’s not read too much into it,” Star Tribune, April 4, 2013, http://www.startribune.com/minnesota-s-labor-force-participation-rate-is-falling-but-let-s-not-read-too-much-into-it/201295331/

[4] Cain Miller, Claire, “Where young college graduates are choosing to live,” New York Times, Oct. 20, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/upshot/where-young-college-graduates-are-choosing-to-live.html

[5] Crosby, Jackie, “Minnesota’s youth exodus spells trouble ahead for labor force,” Star Tribune,” April 18, 2015, http://www.startribune.com/lifestyle/300549671.html

[6] Hamilton, et al., Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas, University of New Hampshire, Carsey Institute, 2008, http://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1040&context=carsey

[7] Leonhardt, Cox and Cain Miller, “An atlas of upward mobility shows paths out of poverty,” New York Times, May 4, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/04/upshot/an-atlas-of-upward-mobility-shows-paths-out-of-poverty.html

[8] “Southwest Minnesota recruitment video available for online sharing,” Pioneer Public Television, May 22, 2015, http://www.pioneer.org/pressroom/southwest-minnesota-recruitment-video-available-for-online-sharing

[9] Walljasper, Jay, “Southeast Minnesota explores how to make hay in the emerging creative economy,” Minnpost.com, June 3, 2015, http://www.minnpost.com/arts-culture/2015/06/southeast-minnesota-explores-how-make-hay-emerging-creative-economy

[10] http://www.dailyyonder.com/study-trends-rural-businesses/2015/07/29/7825

[11] Atlas of Minnesota Online: Housing built before 1940, Center for Rural Policy and Development, https://www.ruralmn.org/atlas-online/?tab=5&report=84

[12] Greater Minnesota Partnership, http://gmnp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Workforce-Housing.pdf

[13] Jonathan Zierdt, Rural Minnesota Radio, June 22, 2015, http://ruralrealitymn.org/2015/06/22/public-transit-in-rural-minnesota/

[14] “Greater Minnesota Transit Plan, 2010-2030,” Minnesota Department of Transportation, December 2009, http://www.dot.state.mn.us/transit/reports/transitreports/greater-mn-transit-plan.pdf

[15] Walljasper, Jay, “Albert Lea shows how walking and other healthy habits can rejuvenate a rural community,” Minnpost.com, May 22, 2015, http://www.minnpost.com/health/2015/05/albert-lea-shows-how-walking-and-other-healthy-habits-can-rejuvenate-rural-community

[16] Werner and Hayes, “The State of Water,” Center for Rural Policy and Development, 2014, https://www.ruralmn.org/publications/state-of-water/

[17] Jay Walljasper, Rural Minnesota Radio, July 22, 2015, https://www.ruralmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/RMR-07-22-2015-Livibility-in-Rural-MN.mp3

Published July 30, 2015